Thursday, October 9, 2025. Annette’s Roundup for Democracy.

Yesterday, Trump target, former head of the FBI, James Comey, pleaded not guilty to trumped up charges against him.

His lawyers asked that the case be dismissed as “vindictive” prosecution.

Comey Pleads Not Guilty and Will Seek to Dismiss Charges as Vindictive.

The former F.B.I. director appeared in a brief hearing in federal court. His lawyers sought clarity on the details of a case filed under pressure from President Trump.

James Comey, the former F.B.I. director targeted by President Trump, pleaded not guilty on Wednesday to charges he lied to Congress. His lawyer said he would move to quickly dismiss the case, calling it a “vindictive” and “selective” prosecution.

Mr. Comey, wearing a dark suit and accompanied by his family, stood to his full 6-foot-8 height to offer his plea, and a “thank you very much,” to District Judge Michael Nachmanoff during a brisk court appearance that began five minutes early and lasted less than half an hour.

If the hearing offered a guide to the defense’s strategy, it revealed little new about a case deemed so weak by career prosecutors in the Eastern District of Virginia that they refused to have anything to do with it. That reluctance forced the White House to quickly insert a stand-in U.S. attorney to file the indictment.

Mr. Comey’s lead lawyer, Patrick Fitzgerald, vented his exasperation in the hearing, saying that his “first substantive contact” with prosecutors came Tuesday night. He said he still had not received specific details of the charges, including the identities of witnesses, beyond the two-page indictment approved by a split grand jury on Sept. 25.

The indictment of Mr. Comey is the most significant legal action yet taken against those Mr. Trump has publicly targeted for retribution. It came shortly after the president all but commanded Attorney General Pam Bondi to take legal action against Mr. Comey; Senator Adam B. Schiff, a California Democrat; and New York’s attorney general, Letitia James.

If the intention of Mr. Trump and his allies was to humiliate Mr. Comey, they appeared to lose round one.

An uninitiated observer might even have mistaken the defense for the prosecution on Wednesday, given the lopsided power dynamic. To the judge’s right stood Mr. Comey, the former head of the F.B.I. and the Manhattan U.S. attorney’s office, and Mr. Fitzgerald, a former federal prosecutor known for winning convictions in major terrorism and public corruption cases.

On the left, at the prosecutors table, sat Lindsey Halligan, who was making her second-ever appearance as a prosecutor after she was hastily installed by Mr. Trump as the U.S. attorney in the Eastern District of Virginia last month. She was picked after her predecessor was ousted after finding insufficient evidence to indict Mr. Comey.

Ms. Halligan, a former insurance lawyer, did not speak in court. Instead, she spent the hearing rocking and nodding in her chair as a junior federal prosecutor brought in from North Carolina spoke for the Justice Department.

Once Mr. Fitzgerald requested a jury trial on Mr. Comey’s behalf, Judge Nachmanoff, a Biden appointee and former federal public defender, made it clear he wanted a move quickly. He initially suggested the matter could be wrapped up by mid-December but set a trial date of Jan. 5 after both sides wanted a bit more time.

The prosecutor, Nathaniel Tyler Lemons, drew the judge’s impatience when he suggested that the government needed time to introduce classified evidence and argued that the case, which hinges on a single accusation that Mr. Comey lied during a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing, was complex.

“I’m a little skeptical,” Judge Nachmanoff replied. “This does not appear to me to be an overly complicated case.”

Mr. Comey’s arraignment, for all its brevity, was considerably more eventful than typical preliminary proceedings.

In the most significant development, Mr. Fitzgerald said he intended to file two motions to dismiss the case. The first will accuse the government of “vindictive” and “selective” prosecution based on Mr. Trump’s public demand that Mr. Comey be prosecuted. The second will seek to challenge what he called the illegal appointment of Ms. Halligan as U.S. attorney.

Judge Nachmanoff said he would rule on the first and outsource the question of Ms. Halligan’s appointment to another judge.

The government told the judge that it expects Mr. Comey’s trial to last two to three days. The judge tentatively scheduled a follow-up hearing later this month and released Mr. Comey on his own recognizance with no restrictions on his travel or other activities.

Politics shadowed the sunny sixth-floor courtroom, crammed to overflow with reporters, supporters of Mr. Comey and a small contingent of local residents.

A handful of protesters staged a decorous, nearly noiseless anti-Trump protest outside the courthouse, including one woman who brandished a sign that read “Show Trial.”

Mr. Comey faces up to five years in prison if convicted, though many current and former prosecutors believe the case will be difficult to prove — if his lawyers do not succeed in getting the charges quickly dismissed. He made no immediate public comments after the hearing.

Ms. Halligan, who narrowly secured a two-count indictment after a shaky solo appearance before the grand jury, has had a hard time getting anyone in her new office to help her with the case, according to current and former prosecutors in the office.

Two prosecutors who work in the Eastern District of North Carolina, Tyler Lemons and Gabriel Diaz, gave official notice on Tuesday that they had been assigned to the case, according to court records.

The case has cast a corrosive pall over the Eastern District of Virginia, one of the most important federal prosecutor’s offices in the nation.

Erik S. Siebert, the district’s former U.S. attorney, came under pressure from Mr. Trump after telling his superiors in the Justice Department that there was not enough evidence against Mr. Comey or, in a separate potential case, Ms. James. Mr. Siebert quit on Sept. 19, hours after the president called for his ouster.

Since then, Justice Department appointees have fired without cause two career prosecutors who also objected to the Comey indictment. Other officials in the Eastern District of Virginia have applied for jobs on the outside or have written memos justifying their actions in case they have to contest personnel actions or sue the department.

The bare-bones, two-page indictment against Mr. Comey was signed only by Ms. Halligan, a former defense lawyer for Mr. Trump who had been serving as a midlevel lawyer in the office of the White House staff secretary.

Mr. Comey was indicted on one count of making a false statement and one count of obstruction of a congressional proceeding in connection with his testimony before a Senate committee in September 2020.

Court records indicate that Ms. Halligan also failed to get the grand jury to indict Mr. Comey on a second false statement charge. (New York Times).

"Daniel Richman—a law professor who prosecutors allege Comey authorized to leak information to the press—told investigators that the former FBI director instructed him not to engage with the media on at least two occasions and unequivocally said Comey never authorized him to… https://t.co/DbY8OFYp8w

— George Conway 👊🇺🇸🔥 (@gtconway3d) October 9, 2025

One more thing.

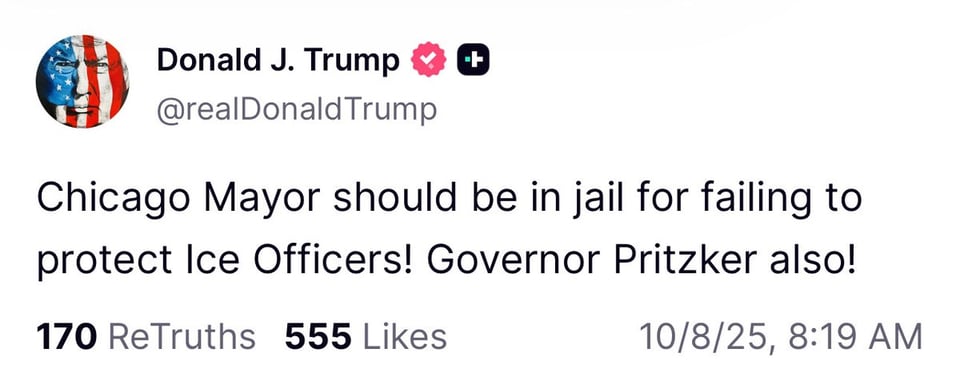

Yesterday, Trump continued to spew venom and seek retribution against those who oppose him.

While Trump and his cronies continue to threaten furloughed federal workers with permanent loss of pay, others fight back.

IRS tells employees furlough backpay guaranteed, while WH counters in memo

The Internal Revenue Service said in a Wednesday memo that federal workers are required by law to be paid for the period that they're furloughed during a government shutdown — a day after Axios first reported on a draft White House memo that argued the opposite.

The big picture: That acknowledgement is a likely relief for the hundreds of thousands of federal employees who face being furloughed each day of a government shutdown.

But it seemingly contradicts the analysis from the White House, which offered a different interpretation of the Government Employee Fair Treatment Act of 2019 that President Trump signed during the last government shutdown, per reporting from Axios' Marc Caputo.

Driving the news: A letter from Acting IRS Human Capital Officer David Traynor to IRS employees stated that although workers would be "placed in non-pay and non-duty status during the furlough," GEFTA requires that federal workers who are "furloughed or required to work during a lapse in appropriations to be compensated for the period of the lapse."

It adds that they must be compensated on the "earliest date possible" after the lapse comes to a close.

Catch up quick: The Office of Management and Budget memo arguing the law had been misconstrued sparked bipartisan discomfort.

Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.) told Axios's Andrew Solender that the "law is simply not on the side of Trump's threats to withhold pay from federal employees that he somehow disfavors."

But House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) argued at a press conference that "there are some legal analysts who are saying that that may not be appropriate or necessary in terms of the law requiring that back pay be provided."

The fine print: The contention in the draft memo centered around the phrase that furloughed employees would be compensated "subject to the enactment of appropriations Acts ending the lapse."

According to the White House argument, that means money for those workers needs to be specifically appropriated by Congress. Asked about not paying furloughed workers, Trump told reporters, "it depends on who we're talking about."

But attorneys and other advocates for federal workers say that's a clear misreading of the law's intent.

Zoom out: The IRS said an "IRS-wide" furlough began Wednesday for everyone who was not already identified as excepted or exempt. According to its updated contingency plan, that means nearly half of the IRS workforce is to be furloughed.

"Due to the lapse in appropriations, most IRS operations are closed," the agency said. (Axios)

Senate Majority Leader John Thune told ABC News on Wednesday that the thousands of furloughed federal workers will get back pay when the government shutdown ends. https://t.co/CwJ6P8d4Yv

— ABC News (@ABC) October 9, 2025

What civil society can do to beat Trumpism?

President Trump is trying to seize power that he is not entitled to under the law or the Constitution.

But Mr. Trump will fail in remaking American politics if people and institutions coordinate against him, which is why his administration is targeting businesses, nonprofits and the rest of civil society, proposing corrupting bargains to those who acquiesce and punishing holdouts to terrify the rest into submission.

This is one part of Mr. Trump’s bigger agenda to remake American politics so that everyone wants to be his friend and no one dares to be his enemy. If the administration can reshape politics in such a way, it can create an enduring advantage for itself, as Prime Minister Viktor Orbán of Hungary and President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Turkey have done.

The most recent example: Last week the Trump administration announced that it was sending an academic “compact” to nine universities. Administration officials are weaponizing federal funding to make universities more congenial to Trumpism, saying that those who sign the compact will be at the front of the line for government money.

The administration is targeting a small group of schools, which it describes as possible “good actors.” It hopes that if institutions like Brown and the University of Virginia roll over, others will submit, too.

It wanted to signal strength. Instead, it’s revealing its weakness. The administration’s need to break the academy is forcing it to make a desperately risky gamble.

As political theorists like Russell Hardin have explained, power is a “coordination game,” in which everything depends on what the public believes and does together. Even the most brutal tyrant does not have enough soldiers and police officers to compel everyone to obey at gunpoint. Authoritarian regimes need civil society — the realm of people and organizations outside government control — to acquiesce to their rule. East Germany’s dictatorship collapsed when multitudes began to march and organize against it, collapsing the illusion that everyone accepted tyranny.

The struggle over regime change is about whether the aspiring authoritarians can subdue civil society. Their strategy is to play divide and conquer, rewarding friends and brutally punishing opponents. They win when society cracks, creating a self-enforcing set of expectations, in which everyone shuts up and complies because everyone expects everyone else to shut up and comply, too.

Those who oppose authoritarianism have to play a different game, creating solidarity among an unwieldy coalition, which knows that if everyone holds together, they will surely succeed. This too can become a self-reinforcing set of expectations — but only if the coalition’s members resist the threats and promises of those who are trying to break it.

The public can be extraordinarily powerful when it pushes back. When ABC suspended Jimmy Kimmel’s show under administration pressure, its parent company, Disney, reportedly began hemorrhaging subscribers. Public outrage made Disney change its mind and bring Mr. Kimmel back. Other businesses — especially businesses that are exposed to the public — may be less likely to concede to noxious administration demands.

Mr. Trump’s basic untrustworthiness is another big turnoff for would-be turncoats. He never lets gratitude get in the way of self-interest. Those who submit to him just expose themselves to relentless demands for more.

Universities have taken note. Although the Trump administration forced Columbia into humiliating subjection and has won some concessions from other universities, it hasn’t succeeded in creating the general sense of self-reinforcing hopelessness in the academy that it wanted to. Some institutions are negotiating, but few seem on the verge of folding to the same degree.

That explains why the Trump administration has announced the compact, and why it is unlikely to work. The compact aims both to break any opposition and to create a system under which universities will agree to what amounts to ideological oversight. If every university that depends on federal funding believes that every other university will sign, no one will want to be the last one left behind on Mr. Trump’s enemy list.

That is likely why the compact was sent to the group that it was, combining elite private and public institutions that might be wobbly, with the University of Texas at Austin, whose Board of Regents is chosen by a Republican governor and confirmed by a Republican state senate and has already expressed its enthusiasm for the deal. If the other schools follow U.T. Austin’s suit, they might break solidarity and provoke a rush to agree to the administration’s terms across the whole academy.

But that depends on fear of a credible threat. The administration would have played its cards differently if it had a stronger hand. Its best outcome would have been a private deal under which the nine universities announced simultaneously that they were signing onto the compact. Such an announcement might indeed have panicked other universities around the country.

That this didn’t happen suggests that the administration’s threats aren’t enough on their own to compel submission.

Instead, the Trump administration is betting its chips on public pressure. That is enormously risky, because it provides a big opportunity for the opposing coalition and encourages the public to get involved on the other side. Alumni will get organized, pressing university leaders not to sign a compact that could well permanently ruin their reputations. Students demonstrating against the imposition of ideological controls will likely win broad support and sympathy, even from those who have opposed recent campus protests. Some academics are condemning the compact and threatening boycotts, while Dartmouth College’s president has responded by saying she will always defend her university’s “fierce independence.” California’s governor, Gavin Newsom, has threatened to pull state funding from any institution that signs. U.T. Austin’s academic superstars might well have begun to get emails from other institutions, asking if they are interested in moving.

This battle holds bigger lessons. The greatest weapon that the forces of regime change possess is the fear of inevitability. If everyone believes that Mr. Trump will succeed in reshaping America, he will.

The best defense against this weapon is solidarity among groups who disagree ferociously on many questions, but who agree on the need to keep America democratic and rebuild institutions and social connections to make democracy more robust. As the political scientist Adam Przeworski points out, Polish pro-democracy forces won only when they agreed to leave aside their bitter divisions over abortion until after they had succeeded.

Our future depends on who can coordinate best and how Americans answer the two most urgent questions in our politics: Will the administration succeed in picking off enough of the opposition such that resistance seems useless? Or will civil society hold firm against a regime that wants to center all power on itself? (Op-Ed, Henry J. Farrell is a professor of democracy and international affairs at Johns Hopkins. New York Times).