Thursday, October 5, 2023. Annette’s News Roundup.

I think the Roundup makes people feel not so alone.

To read an article excerpted in this Roundup, click on its blue title. Each “blue” article is hyperlinked so you can read the whole article.

Please feel free to share.

Invite at least one other person to subscribe today! https://buttondown.email/AnnettesNewsRoundup

Joe is always busy.

Earlier this year, we were on the verge of getting millions of Americans student debt relief.

— President Biden (@POTUS) October 4, 2023

Republican elected officials and special interests blocked it.

Now, we're pursuing another path grounded in the Higher Education Act.

And we're not backing down.

The New York Times reports - “Biden Cancels an Additional $9 Billion in Student Loan Debt.”

The move comes just three days after student loan repayments resumed following a three-year pause.

________________________________

Kamala is always busy.

Wednesday’s Roundup didn’t show this important moment well, so here goes again. 👇

The Vice President swears in the new Senator from California, Laphonza Butler. 1 minute. 43 seconds. Watch and smile.

________________________________

Who will the GOP make the next Speaker.

Scalise and Gym Jordan want the job.

What do you make of this? Posted by Trump on Truth Social.

Remember the Speaker doesn’t have to be a member of the House.

_________________________________

I know you want to read this.

Giuliani’s Drinking, Long a Fraught Subject, Has Trump Prosecutors’ Attention.

Rudolph W. Giuliani had always been hard to miss at the Grand Havana Room, a magnet for well-wishers and hangers-on at the Midtown cigar club that still treated him like the king of New York.

In recent years, many close to him feared, he was becoming even harder to miss.

For more than a decade, friends conceded grimly, Mr. Giuliani’s drinking had been a problem. And as he surged back to prominence during the presidency of Donald J. Trump, it was getting more difficult to hide it.

On some nights when Mr. Giuliani was overserved, an associate discreetly signaled the rest of the club, tipping back his empty hand in a drinking motion, out of the former mayor’s line of sight, in case others preferred to keep their distance. Some allies, watching Mr. Giuliani down Scotch before leaving for Fox News interviews, would slip away to find a television, clenching through his rickety defenses of Mr. Trump.

Even at less rollicking venues — a book party, a Sept. 11 anniversary dinner, an intimate gathering at Mr. Giuliani’s own apartment — his consistent, conspicuous intoxication often startled his company.

“It’s no secret, nor do I do him any favors if I don’t mention that problem, because he has it,” said Andrew Stein, a former New York City Council president who has known Mr. Giuliani for decades. “It’s actually one of the saddest things I can think about in politics.”

No one close to Mr. Giuliani, 79, has suggested that drinking could excuse or explain away his present legal and personal disrepair. He arrived for a mug shot in Georgia in August not over rowdy nightlife behavior or reckless cable interviews but for allegedly abusing the laws he defended aggressively as a federal prosecutor, subverting the democracy of a nation that once lionized him.

Yet to almost anyone in proximity, friends say, Mr. Giuliani’s drinking has been the pulsing drumbeat punctuating his descent — not the cause of his reputational collapse but the ubiquitous evidence, well before Election Day in 2020, that something was not right with the former president’s most incautious lieutenant.

Now, prosecutors in the federal election case against Mr. Trump have shown an interest in the drinking habits of Mr. Giuliani — and whether the former president ignored what his aides described as the plain inebriation of the former mayor referred to in court documents as “Co-Conspirator 1.”

Their entwined legal peril has turned a matter long whispered about by former City Hall aides, White House advisers and political socialites into an investigative subplot in an unprecedented case.

The office of the special counsel, Jack Smith, has questioned witnesses about Mr. Giuliani’s alcohol consumption as he was advising Mr. Trump, including on election night, according to a person familiar with the matter. Mr. Smith’s investigators have also asked about Mr. Trump’s level of awareness of his lawyer’s drinking as they worked to overturn the election and prevent Joseph R. Biden Jr. from being certified as the 2020 winner at almost any cost. (A spokesman for the special counsel declined to comment.)

The answers to those prompts could complicate any efforts by Mr. Trump’s team to lean on a so-called advice-of-counsel defense, a strategy that could portray him as a client merely taking professional cues from his lawyers. If such guidance came from someone whom Mr. Trump knew to be compromised by alcohol, especially when many others told Mr. Trump definitively that he had lost, his argument could weaken.

In interviews and in testimony to Congress, several people at the White House on election night — the evening when Mr. Giuliani urged Mr. Trump to declare victory despite the results — have said that the former mayor appeared to be drunk, slurring and carrying an odor of alcohol.

“The mayor was definitely intoxicated,” Jason Miller, a top Trump adviser and a veteran of Mr. Giuliani’s 2008 presidential campaign, told the congressional committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol in a deposition early last year. “But I do not know his level of intoxication when he spoke with the president.” (Mr. Giuliani furiously denied this account and condemned Mr. Miller, who had spoken glowingly of him in public, in vicious terms.)

Privately, Mr. Trump, who has long described himself as a teetotaler, has spoken derisively about Mr. Giuliani’s drinking, according to a person familiar with his remarks. But Mr. Trump’s monologues to associates can betray a layered view of the former mayor, one that many Republicans share: He credits Mr. Giuliani with turning around New York City after the high-crime 1970s and 1980s and contends that it has suffered lately without him in charge. Then he returns to a lament about Mr. Giuliani’s image today.

Mr. Trump does not dwell on his own role in that trajectory.

In a statement that did not address specific accounts about Mr. Giuliani’s drinking or its potential relevance to prosecutors, Ted Goodman, a political adviser to the former mayor, praised Mr. Giuliani’s career and suggested he was being maligned because “he has the courage to defend an innocent man” in Mr. Trump.

[According to] Andrew Kirtzman, the author of “Giuliani: The Rise and Tragic Fall of America’s Mayor,” published last year - Literally falling-down drunk,” Mr. Kirtzman said in an interview, noting that several incidents over the years, in Ms. Giuliani’s telling, required medical attention. Mr. Kirtzman said that he came to consider Mr. Giuliani’s drinking “part of the overall erosion of his self-discipline.”

To read the whole article on Giuliani, click here.(New York Times).

________________________________

Leonard Leo says he will not cooperate with D.C. Attorney General tax probe.

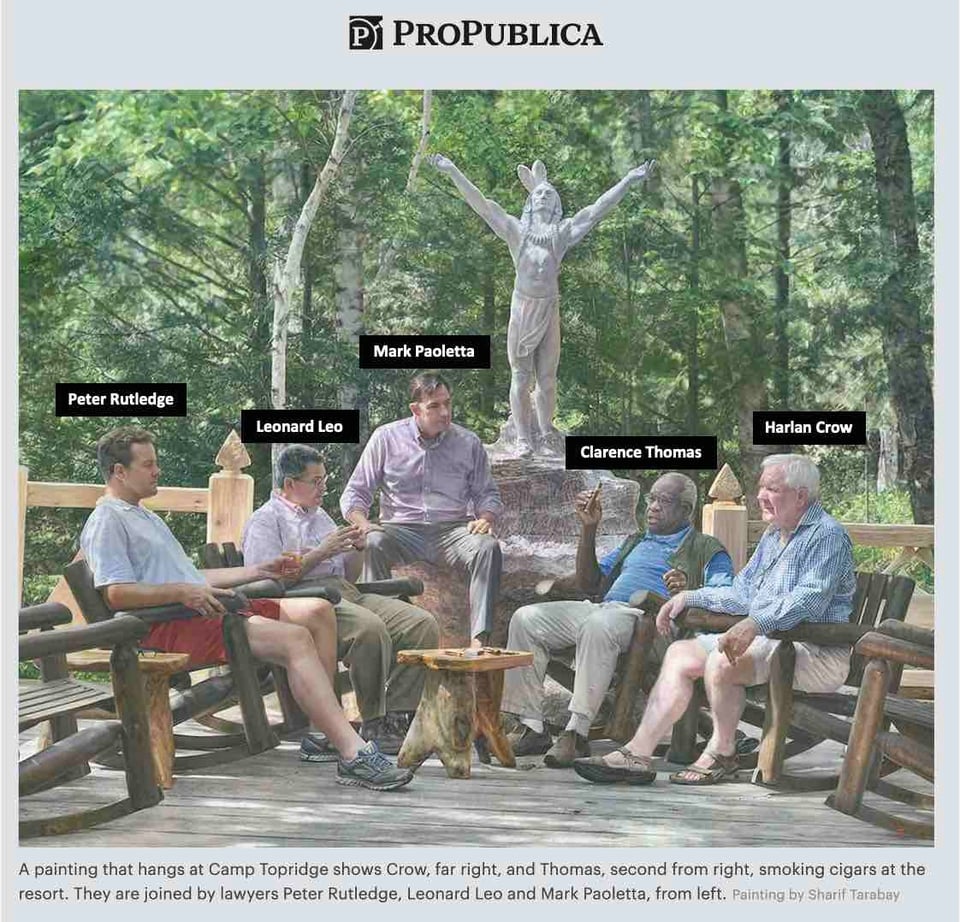

Remember Leonard Leo?

From the article below, 👇 “Leo is considered the architect of the ultraconservative Supreme Court who recently received a $1.6 billion contribution, believed to be the biggest political donation in U.S. history, from a far-right billionaire. Trump chose his three Supreme Court picks, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, from a list drawn up by Leo.” The photo below 👇 should remind you too.

This story may be the start of something big.

Judicial activist Leonard Leo is not cooperating with an investigation by Washington D.C. Attorney General Brian Schwalb for potentially misusing nonprofit tax laws for personal enrichment, his attorney confirmed.

David Rivkin, Leo’s attorney, said in a statement to POLITICO that Schwalb has “no legal authority to conduct any investigatory steps or take any enforcement measures” because Leo’s multi-billion-dollar aligned nonprofits — which poured millions into campaigning for the nominations of conservative Supreme Court justices and advocating before them — were organized outside of D.C.

Leo’s consulting firm, CRC Advisors is registered in D.C. and his main aligned nonprofit, The 85 Fund, used a D.C. mailing address for at least a decade.

Schwalb is also looking into liberal “dark money” group Arabella Advisors, a consulting firm founded by a former Clinton official that manages a handful of nonprofits, POLITICO confirmed, after Republican attorneys general recently complained that Schwalb should instead be probing Arabella.

“Arabella Advisors complies with the law and will cooperate with the District of Columbia Attorney General’s civil inquiry,” said Arabella spokesman Steve Sampson said in a statement. “We’re confident in the systems we have in place to ensure our business conforms with legal and regulatory requirements, and Arabella Advisors is proud of the work we do.”

The subpoenas come a few weeks after POLITICO reported that Schwalb is looking into the multi-billion-dollar dark money network aligned with Leo.

The investigations — and subsequent subpoenas — are in response to dueling complaints from liberal and conservative watchdog groups filed with the IRS that began after POLITICO reported that the lifestyle of Leo and a handful of his allies took a lavish turn beginning in 2016, the year he was tapped as an unpaid adviser on judicial nominations to former President Donald Trump.

Arabella was targeted in the complaint from Americans for Public Trust, a watchdog mostly funded by DonorsTrust, often described as the “dark money ATM” of the conservative movement which has given millions to Leo-aligned nonprofits and his consulting firm, CRC Advisors. A liberal watchdog, Campaign for Accountability, once affiliated with Arabella, filed a complaint with the IRS and D.C. Attorney General following POLITICO’s reporting on Leo’s lifestyle.

A Wall Street Journal op-ed last week said Schwalb lacks jurisdiction to investigate since Leo’s aligned groups are located in Virginia or Texas and criticized him for failing to investigate Arabella. It cited a recent letter sent to Schwalb from a dozen Republican state attorneys general.

The opinion piece did not note that a Leo-aligned group has been the top donor to the Republican Attorneys General Association or that The 85 Fund, one of Leo’s primary aligned groups, quietly relocated in recent months from the capital area to Texas amid the investigation. The 85 Fund had been incorporated in Virginia for nearly 20 years but it was using a UPS drop box in D.C.’s Georgetown neighborhood as its principal office address.

The conservative watchdog’s complaint, filed in mid-August, asked the Internal Revenue Service to investigate whether Arabella’s founder, Eric Kessler, took in funds that exceeded fair market value in exchange for services provided by his nonprofits. It claims that more than $228 million has been “diverted” back to Arabella over the past two decades.

Leo has long pointed to Arabella as his inspiration in creating his network of nonprofits which have poured tens of millions of dollars over the past decade to promote Trump’s Supreme Court picks, file briefs before the court and, more recently, used an alias to push for voting restrictions and accuse Democrats of cheating in the 2020 election.

Liberals cite significant differences between Arabella and Leo’s network, much of it registered as “charitable” and “social welfare” groups managed by a handful of allies.

Leo is considered the architect of the ultraconservative Supreme Court who recently received a $1.6 billion contribution, believed to be the biggest political donation in U.S. history, from a far-right billionaire. Trump chose his three Supreme Court picks, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, from a list drawn up by Leo.

Arabella, which says on its website that it focuses on “philanthropy” and “impact investing,” acts as a vendor to nonprofit groups to supply human resources, legal and other administrative services. It has stressed that it does not direct the spending decisions of its clients whereas Leo has declined to say what services were provided in exchange for $43 million which has flowed to his company over two years.

Schwalb, who took office in January, has a background in tax law and served as a trial attorney in the tax division of the Department of Justice under former President Bill Clinton.

________________________________

Facts that need wider distribution.

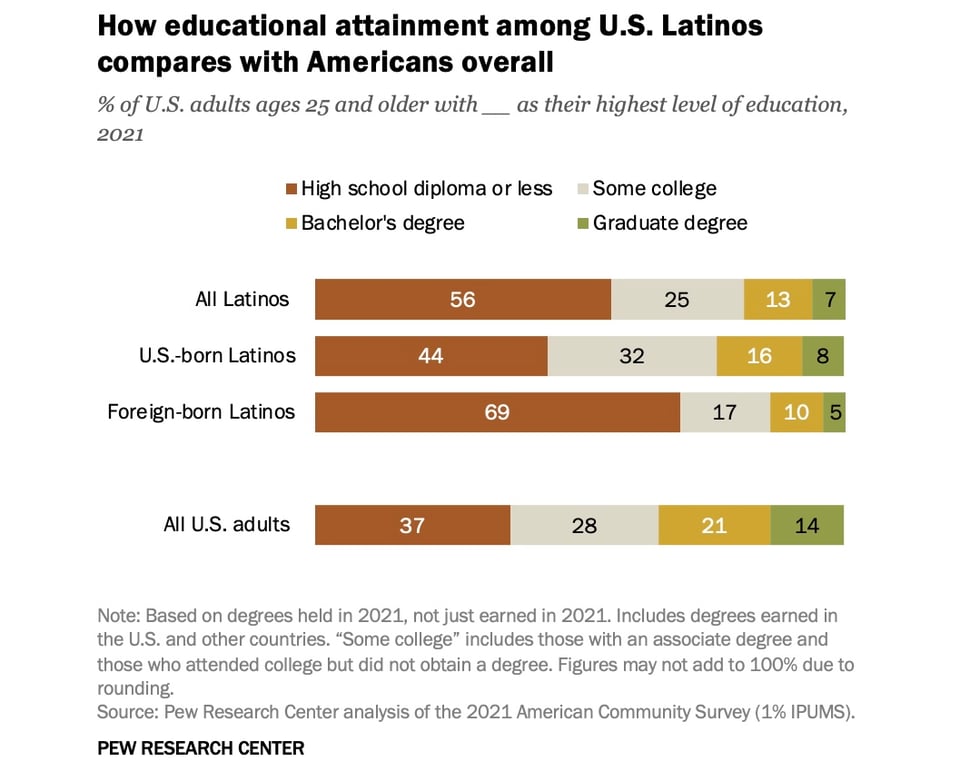

NEW: In 2021, nearly 2.5 million Latinos in the U.S. held advanced degrees such as a master’s or a doctorate. Here are key facts about these degree holders, and about how their numbers have changed over time. https://t.co/w2Gkc7XxuL

— Pew Research Race and Ethnicity (@pewidentity) October 3, 2023

Some excerpts from the Pew Report.

This represented a huge increase over 2000, when 710,000 Latinos held advanced degrees. The shift reflects Latinos’ broader increase in postsecondary enrollment and rising educational attainment.

Despite the large increase in the number of Latinos with advanced degrees, they accounted for just 8% of all advanced degree holders in the U.S. in 2021. This was far below their 19% share of the overall U.S. population, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of Census Bureau data.

Hispanic Americans have seen the fastest growth in advanced degrees of any major racial or ethnic group.

That includes a 291% increase in the number of Hispanic women holding an advanced degree and a 199% increase in that number for Hispanic men between 2000 and 2021. By comparison, there has been slower growth in graduate degrees among White, Black and Asian Americans.

Women have fueled the growing number of Hispanics with graduate degrees. Between 1990 and 2021, the number of Hispanic women with an advanced degree increased by more than a million. The number of Hispanic men with an advanced degree also grew rapidly, though the gain was smaller – about 860,000.

Most Latinos with graduate degrees are U.S. born, but immigrants account for more than a third of the total.

One more thing. Or Two.

On Related Matters.

First. Today, October 5, we observe Latina Equal Pay Day. The date symbolizes how far into the year the average median Latina woman must work (in addition to their earnings last year) in order to have earned what the average median non-Hispanic White man had earned the entire previous year.

52 cents for "all earners" (full time year-round + part time and part year) compared to non-Hispanic White men.

57 cents for full time, year round workers compared to non-Hispanic White men. (Source. Equal Pay Today).

Second.

Without a College Degree, Life in America Is Staggeringly Shorter.

By many measures, the U.S. economy is thriving: Unemployment stands close to the 50-year low set in April, the fraction of people age 25 to 54 in work is at a two-decade high, gross domestic product is growing rapidly, inflation is falling, and the S&P 500 is a third higher than it was before the Covid pandemic.

While encouraging, economic statistics like these offer an incomplete picture of the state of the country. There is a deep and persistent national malcontent: In a recent NBC News poll, nearly three-quarters of Americans surveyed said the United States is on the wrong track, and Gallup reported that poor life ratings are at record highs.

What the economic statistics obscure in the averages is that there is not one but two Americas — and a clear line demarcating the division is educational attainment. Americans with four-year college degrees are flourishing economically, while those without are struggling.

Worse still, as we discovered in new research, the America of those without college degrees has been scarred by death and staggeringly shorter life spans.

Almost two-thirds of American adults do not have college degrees, and they have become increasingly excluded from good jobs, political power and social esteem. As their lives and livelihoods are threatened, their longevity declines.

In the 1970s, American life expectancy grew by about four months each year. By the 1980s, it was similar to life expectancy in other rich countries. Since then, other countries have continued to progress, with life spans increasing by more than two and a half months a year.

But the United States has slowly, gradually and then precipitously fallen behind.

These ever-widening gaps have long troubled demographers and prompted three reports from the National Academy of Sciences. The gaps grew wider during the pandemic.

But even before, not only was life expectancy in the United States far from that of the best-performing countries (Japan and Switzerland), but it was also more than two years lower than that of the other worst performers (Germany and Britain) among 22 other rich countries.

Public health authorities in the United States record educational qualifications at death so that, after 1992, we can calculate life expectancy by college degree, starting at age 25, when most people have completed their education. In new research using these individual death records, we have found startling results.

Life expectancy at age 25 (adult life expectancy) for those with four-year college degrees rose to 59 years on the eve of the pandemic — so an average individual would live to 84 — up from 54 years (or 79 years old) in 1992. During the pandemic, by 2021, the expectation slipped a year.

But we were staggered to discover that for those without college degrees, life expectancy reached its peak around 2010 and has been falling since, an unfolding disaster that has attracted little attention in the media or among elected officials.

Adult life expectancy for this group started out two and a half years lower, at 51.6, in 1992 — so an average individual would live to nearly 77 years old. But by 2021, it was 49.8 years (or almost 75 years old), roughly eight and a half years less than people with college degrees, and those without had lost 3.3 years during the pandemic.

The mortality gap between Americans with and without four-year degrees is widening.

If all Americans had the life expectancy of the college educated, the United States would have been one of the best performers among the rich countries in terms of life expectancy, not the worst. It is the experience of those without college degrees that accounts for America’s failure.

The educational divide is also clear in economic circumstances. Since 1979, wages for those with a B.A. or more far exceeded wages for those with less education. Families without a member with a college degree had a median income that was only 4 percent higher in 2019 than in 1970, compared with 24 percent higher for families where at least one member had a college degree. According to Federal Reserve data, wealth was equally split between those with and without college degrees in 1990, but today three-quarters of wealth is owned by college graduates.

Why is this happening in America? We and others have documented an increase in corporate power relative to workers, which includes the decline of competition, the decline of unions and their ability to raise wages for workers without college degrees and the decreased mobility of workers from less to more successful places.

Other rich countries have been less prone to creating an elite class out of the college educated, while the United States has designed a system that too often works for itself but not for working-class Americans. They have been increasingly excluded from the local and national power that once came with unions and have lost good jobs and wages to excessive health care costs, globalization and automation. Furthermore, the children of the elite rarely serve in the military and increasingly hoard places in top selective colleges.

Unhealthy behaviors are more common among people without college degrees, but those behaviors can often be traced to the environments in which they live, lack of work and community decay, as well as their being targeted by the pharmaceutical industry in the first phase of the opioid epidemic. The destruction of good jobs for less-educated men also helps explain much of the decline in stable two-parent families among non-college-educated men and women. We have also increasingly come to believe that a college degree works through often arbitrary assignation of status, so that jobs are handed out not on the basis of necessary or useful skills but by the use of the degree as a hiring screen.

The divergence with Europe is also striking. European nations generally finance their much less costly health care through government support and not through what is essentially a flat tax on employment (with employer contributions to worker premiums effectively taken out of salary), and its much broader safety net helps people deal with the disruption of jobs.

Other countries do not have Republican-controlled state legislatures passing corporate-friendly measures — on minimum wages, right-to-work laws, guns, pollution or tobacco taxes — that harm the communities, lives and health of less-educated Americans. Nor do they have Republican governors advising some constituents not to get vaccinated.

As the economy has recovered from Covid, less-educated Americans have been doing better in a tight labor market. What we don’t know is whether this improvement will last or peter out as the market weakens, as happened in the past.

What can be done? We could learn from those European countries that have various educational qualifications that fit different kinds of jobs and lack the sharp binary distinction between those with and without college degrees that is so corrosive in the United States.

We are encouraged by the efforts of both public and private employers to remedy this; it is a low-cost policy that could have large benefits. For example, Gov. Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania signed an executive order removing the B.A. requirement for 92 percent of state jobs; similar policies are in place in Utah, Maryland, Colorado, Georgia, South Carolina, Virginia, New Jersey and Alaska.

Anything that reduces health care costs would help, as would eliminating employer-funded health insurance, replacing it with vouchers paid for by general taxation. Fighting NIMBYism (residents’ “not in my backyard” opposition to local development) and expanding affordable housing in successful cities would increase mobility. Job creation under the Inflation Reduction Act is a move in the right direction. Working people would do better with stronger unions and fewer hostile measures such as right-to-work laws.

The suffering of less-educated America is not something that must happen, nor is it a necessary price to be paid for progress for the rest of us. Indeed, we find it hard to imagine that an educated elite can prosper indefinitely without a better future for everyone else. (New York Times).

________________________________

October 4th was a big day in 1950. Party, folks.

This is Snoopy. He made his debut in Charles Schulz's Peanuts comic on this day (Oct. 4) in 1950. Originally walking on four legs, Charlie Brown's black-and-white beagle evolved to become the world-famous phenomenon we know and love today. 15/10 would be an honor to pet pic.twitter.com/OdxtR4uuqi

— WeRateDogs (@dog_rates) October 4, 2023

_________________________________

Big Day in 1992 too.

31 years, and a lifetime to go. I love going through life with you by my side, @BarackObama. Happy anniversary, honey! ❤️ pic.twitter.com/Hvz0JbhiW8

— Michelle Obama (@MichelleObama) October 3, 2023

_________________________________