Thursday, August 21,2025. Annette’s Roundup for Democracy.

No Politics Thursday.

This is a mid-week pause, an opportunity to think about the past - the New York Department Store, Barney’s, from a chapter excerpted from a new book by one of the Pressmans, the legendary family that founded and ran Barney’s - and the future - Waymo, the self-driving car, and its co-CEO, a black woman. The future of the self-driving car may well be here, in NYC this fall.

This Roundup will end with a brief nod to the past, the present and the future - but not politics. There is more to life.

Hope you enjoy.

When Barneys Held the Greatest Fashion Show

Madonna modeled. Gaultier and Lagerfeld designed jackets. And John Galliano snatched a wig off the runway.

On October 20, 1986, New York splashed Barneys across its cover, underneath a giant headline that mimicked our own painstakingly redesigned logo: “Dressing Up Downtown.” There we were, staring out at you from the newsstand, or up at you from the breakfast table, the Pressman boys, Gene and Bob, arms crossed to indicate serious business, me grinning in a brown and beige houndstooth cashmere jacket by Hermès, Bob starchy and buttoned up with navy blazer. We were leading a charge: Behind us was a phalanx of mannequins that looked like they’d been freed from some Art Deco department store of the ’30s with strong, chiseled, slightly androgynous faces and broad shoulders. They made the usual mannequins look like scrawny waifs. The implication was clear: These goddesses, like us, were ready to go to war. The stakes were lost on no one, certainly not the magazine. “Barneys makes the big time,” the cover announced.

Since first introducing women’s clothing in 1976, we had been building up quickly, but the women’s store represented an exponential leap. We knew we had to make a statement to compete with the best, and we weren’t shy about saying that that was exactly the goal. Everything would be expanded. Shoes. Eveningwear. Whole new departments for things we’d never carried before but that you couldn’t have a women’s store without, like lingerie and cosmetics. The contemporary department would get not just its own floor but its own adjacent building and, finally, a name that would stick: the Co-op, befitting the building’s original use (the apartments remained upstairs). Between our three stores — men’s, women’s, and the Co-op — the little shop that my grandfather Barney opened in 1923 would now take up an entire city block on Seventh Avenue and halfway down 17th Street toward Sixth.

Through sheer force of will, Barney had turned a little discount shop into a monolith. Among the plugged-in of New York and Los Angeles, Barneys would become something beyond a known quantity. Celebrities loved shopping with us and would bring their friends; our personal shopping team had to grow to keep up.

At one point not long after opening, one of downtown’s top personal shoppers, Louise Maniscalco, was paged away from working with Danielle Steel to help Michael Jackson, who was waiting in her office. Another time, she was fitting Robert De Niro for a suit when she got word that his old friend and co-star Al Pacino was coming in. “Let me be his fitter,” De Niro told her. “I’m going to come in when you’re fitting him and be his tailor.” And Louise will never let me forget that time I insisted that she go down to the restaurant after my lunch with two new friends to offer them her services: Tom Cruise and his then-wife Mimi Rogers. They were in a clinch, basically on each other’s laps at that point — Barneys had that effect on some people. “He’s my friend; go interrupt them,” I told her. And because I was her boss — and for no other reason — she did. “And they both looked at me,” Louise remembers, “Like, Are you nuts?”

We Pressmans had grown into a formidable clan. Barney had retired in 1975, and Fred, who had joined his father’s business in 1946, was running the show. Fred and Phyllis’s four kids — me, Bob, and our sisters Nancy and Liz — all worked for Barneys in some capacity, with me and Bob taking the senior-executive roles, me overseeing merchandising and marketing, and Bob finance.

At Fred’s 70th birthday party in 1993, Liz’s then-husband Seth, who always had a video camera handy, captured the family for posterity — captured, in many cases, more than we bargained for. Watching these videos now, you see a large, bumptious, loving clan but also one starting to strain under the pressure of many different personalities living, loving, and working together. We’re all, for better or worse, true to ourselves. Liz and Nancy are fighting. “Oh, I can’t handle this!” Phyllis moans, holding her baby grandson David, one of Liz’s sons. Bob is being Bob: He sallies up to the camera and blows a kiss with both middle fingers up as he does. Bonnie has receded quietly to the sidelines, playing with little bowl-cutted Keith as chaos rages around her. I am, customarily, unbothered and unhurried as everyone else carps and complains. “Who are we waiting for?” someone asks. “Let’s all guess,” Bob says. (The camera comes and finds me: I’m in the shower.) “It’s not fair,” Liz wails. “It’s all for Gene. It’s always been grouped around Gene. No, really, Gene, this has all been grouped around you.”

“This is your typical outing of this family here,” Fred narrates to Seth, who trains the camera on him. “Fighting is just about to begin. I would say that in about five minutes, everybody will be primed up, normally primed up, and everybody will be doing their thing. Screaming, arguing.”

“Is this part of the magical mix?” you can hear Seth asking from behind the camera — the mix we used to say made Barneys, Barneys.

“This is part of the magical mix that the Japanese bought,” Fred says — by 1993, we had closed a major deal to expand Barneys nationally and internationally, funded by Isetan, the major Tokyo-based store chain. “The only problem is they never saw it on TV.”

“Is it the magical mix or magical myth?” Seth says.

“It happens to be both,” says Fred. “This the magical mix and also the myth. And it’s a total mix‑up. This is what they bought, and if this film ever got out, we’re roooooned.” He’s joking, drawing out the word for effect. Isn’t he? “Ruined,” he repeats. “Don’t ever let this film out — make one copy, and keep it in a vault somewhere.”

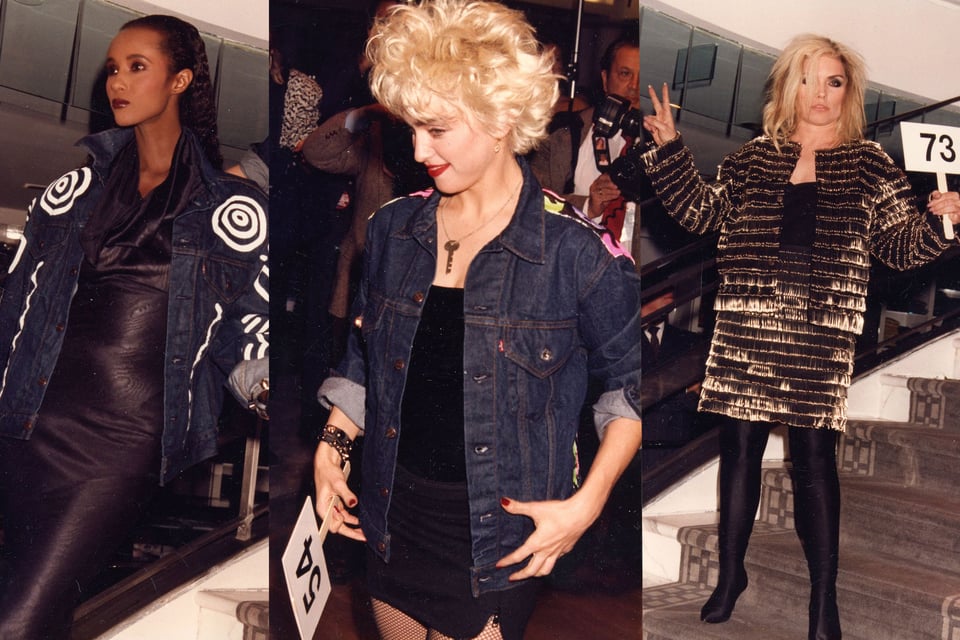

Kate Pierson of the B-52’s and the stylist Elizabeth Saltzman modeled at the same fashion show.

But in 1986, all of that was ahead of us. The women’s store, like other Pressman productions, seemed to be plagued by delays and unforeseen disasters. “Everything that could go wrong did,” was how one of the partners at our architects, Beyer Blinder Belle, summed it all up. The budgets were overrun and then overrun again. That, of course, is what New York captured for its cover story. “Does the name Michael Cimino ring a bell?” it asked its readers, referring to the Oscar-winning director of The Deer Hunter whose follow-up had been a historic and costly bomb. “Will Barneys become the Heaven’s Gate of retailing?”

When the store was finally ready in September 1986, a sniping press corps couldn’t help but point out the delays. “Barneys Unveils Women’s Store (At Last),” wrote the Times. But even the snarkiest gadfly had to admit we had gotten it right. “The new Barneys is at least the equal of the best of its kind in New York,” the paper wrote.

You had to see this store. Elegant but also clever. Tasteful but also funny. So many ideas that we later implemented on a larger scale uptown began life on Seventh Avenue. We had scouted, and shopped, and flea-marketed, and haunted auctions for it, and nothing was box-standard. The display cases were by Ruhlmann. The hostess desk was Portneuve. The chairs were by Robert Oerley. The furniture was antique — I was at the height of my Deco–Wiener Werkstätte obsession, the turn-of-the-past-century design movements. Andrée’s staircase. A skylit atrium. Walls of glass. Peter Marino said it best: We were making a modern classic. The windows opened directly into the store, luring in customers taken with the winding staircase within, the row of individual ground-floor shops meant to emulate Paris’s Rue Saint-Honoré.

Major labels had their own little sections, and the process of coaxing them in had taken years, sweet-talking Carla Fendi, one of the five sisters who ran Fendi with an iron fist, the Dumas family of Hermès, and the Wertheimers who owned Chanel, some of the Frenchest Frenchmen I’ve ever known, into selling to us. We had one for our own label — we started making Barneys bags before many of the other stores thought to do it — and one for fine jewelry, which started out with about five pieces and became one of the defining features of Barneys. I thought it would be fun to display the jewelry around an aquarium stocked with live fish who swam right around the pieces. We’d come to be known for those aquariums, which we later brought uptown, too, and, for their inhabitants, an ongoing source of both pride and headache for the staff. “Who fed the fish?” someone would always be asking in the office. “Did anybody feed the fish? Somebody needs to feed the fish!”

When people today realize I was the guy behind the curtain at Barneys, what they all want to know is why there’s nothing like it anymore. And there are a lot of reasons, but the real one, the truest one, is that nobody kills themselves to merchandise the way that we did. We wanted to give our clients an adventure. You had to seek out what you needed and make what you couldn’t find. You couldn’t just bring in Hermès and rest on your laurels; you had to source the best vintage Hermès, from the great collector Didier Ludot in Paris, and display it in antique Ruhlmann cases — even if Hermès got pissed about it, which they did, because they weren’t making any money on the secondhand stuff. Who cares? It wasn’t all about money.

Many years later, when Barneys was in different hands, some bean counter ran the numbers and couldn’t figure out why we had a little hat display on the ground floor. It wasn’t about selling hats. It was about the charm of the experience, the old-worldliness of it; women would drift over and try on those hats, hats like their mothers and grandmothers wore. They didn’t need to buy them. They loved them. And they bought elsewhere — a lipstick, a handbag, a Chanel suit upstairs. A hat isn’t a line on a spreadsheet. A hat is a merchandising experience.

Eight hundred attendees joined the show at the Barneys women’s store on Seventh Avenue. Cornelia Guest, seen holding No. 36, modeled.

Looking back, the women’s store on Seventh Avenue was a milestone for Barneys, much like my father’s International House had been 16 years earlier, where he introduced Americans to the best of European fashion, most especially his prized discovery, Giorgio Armani. Back then, he had celebrated the opening with a cocktail party, with Hubert de Givenchy and New York’s Mayor John Lindsay in attendance and Bobby Short on the keys. This time around, we had something a little different in mind.

The de facto opening party would take place a month after we were finally in business. We’d take the occasion to stage a charity fashion show and auction off the clothes to raise money for St. Vincent’s Medical Center, our near neighbor, down the road on Seventh Avenue and 12th Street and home to one of the city’s only dedicated AIDS wards. In the end, the party became the opening that mattered most. Slowly, and then all at once, HIV and AIDS had broken into the American consciousness. By 1986, there was no avoiding it, especially for those of us who worked with and among gay men.

From the day I joined the store, gay men and women had been part of my orbit. Gay men were among our best customers when we began carrying serious fashion, early adopters and devotees. They were among our best salespeople. They were our neighbors, especially as Chelsea developed and became the “gayborhood” it is today. New York’s oldest still-going gay bar, Julius’, was a few blocks south, and a few blocks west, the Chelsea piers, where gay men gathered to sunbathe and fuck in the last years of prelapsarian innocence before the virus really took hold.

Anyone who saw AIDS at close range was forever changed. I’ll never forget seeing Chester Weinberg, a fixture of the Garment District, getting pushed around in a wheelchair, looking like he was 90 years old—he was in his 50s. And once these men got sick, they began to die, one after the other after the other. The model agent Zoli — died, 1982. Klaus Nomi, the downtown-denizen performance artist who sang backup for David Bowie alongside Joey “Fiorucci” Arias — died, 1983. Joe McDonald, the first male supermodel — died, 1983. Closer to home, Sergio Galeotti, Armani’s partner, who had broken bread with Fred as they hammered out Armani and Barneys’ exclusive deal — died, 1985. Chester — 1985. Perry Ellis, probably America’s biggest menswear designer after Ralph Lauren — died, 1986, six months after his partner, Laughlin Barker. Willi Smith and Isaia, whose clothes we couldn’t keep in stock — 1987 and 1989. Francis Menuge, Gaultier’s partner — 1989. Charlie Suppon, a designer and a big, gay hulk of a guy who used to say hello by punching me in the chest — 1989. Steve Rubell, my friend, my frat brother, whose funeral I attended in 1989. He had been the party king of New York City, the genius of Studio 54, but in the end, his good-bye was a small, mostly family affair.

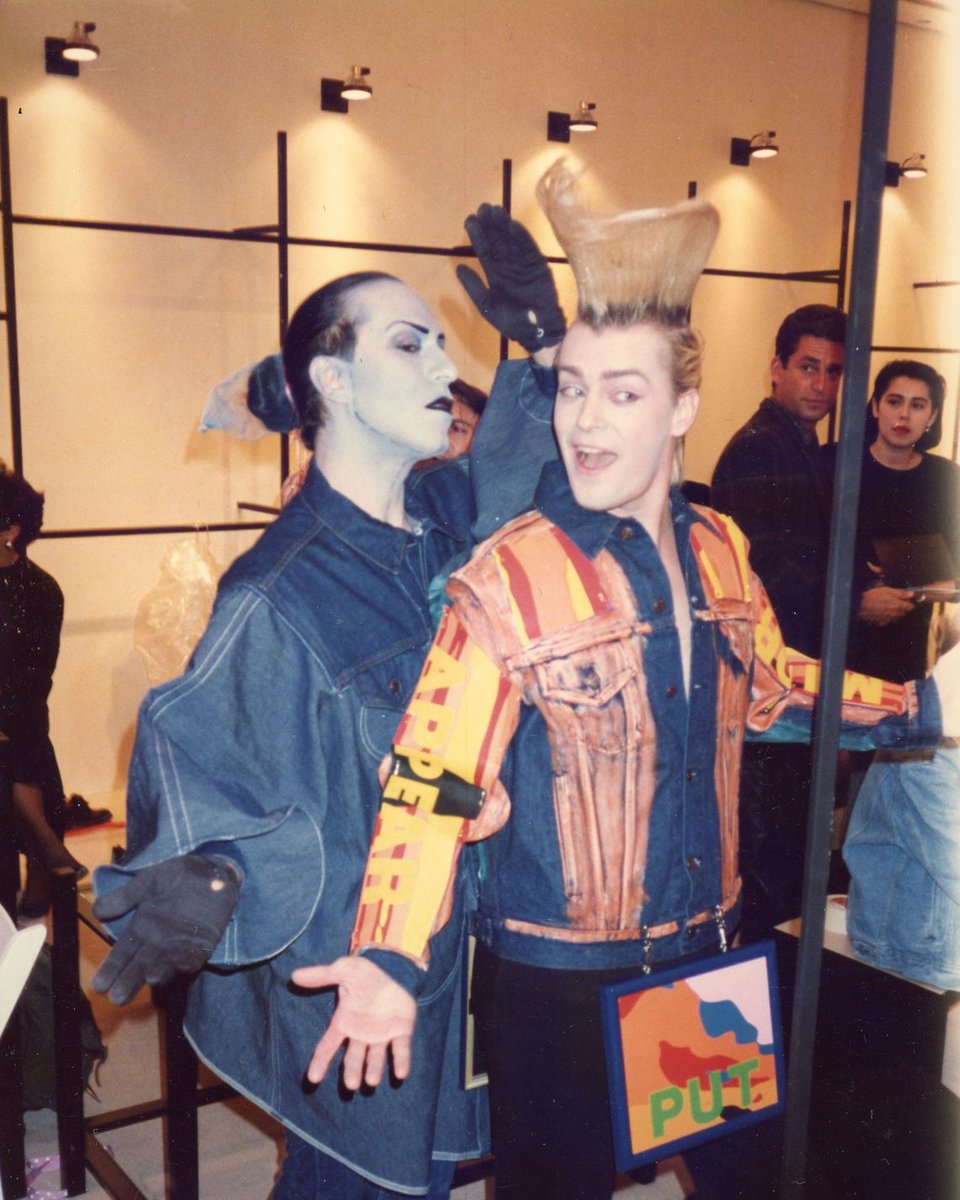

Joey Arias and John Sex.

Bethann Hardison

Nell Campbell

André Leon Talley

Nor was Barneys itself immune. In the sales ranks, and in Simon Doonan’s display department, a number of people were directly affected or had the disease themselves; a lot of them died. “If you were in the art world, the fashion world, and or the gay world, you were like walking through hell.” Simon says. “And if you weren’t, then you weren’t. It wasn’t because people didn’t care. It was because they just weren’t dealing with it.”

I didn’t know it at the time, but it was AIDS, in part, that brought Simon to Barneys from Los Angeles in 1986. He had recently lost a boyfriend to the disease, one of many in the worlds of art, design, and fashion who were dying at a merciless pace. “It was just relentless,” Simon told me many years later. “A lot of our friends were dying. We all thought we were dying.” Tests were new, and not terribly reliable, and no one really got them at that point anyhow. They simply hoped for the best as well as they could and lived like they were all going to die. Simon was grieving, and a friend — who later died — encouraged him to get out of town, try something new. New York was an escape for Simon. He went back to L.A., held a garage sale of all his stuff, and came back to New York to start over. Why not?

Barneys was an effective distraction. The days were long, for all of us. Fred didn’t like people to leave before the store closed at nine, so the workday could easily run to 12 hours. People worked like crazy. For the merchants who traveled, it wasn’t unusual to work five straight days in the store, fly to Europe Friday night, and hit the ground running with shows and showrooms Saturday morning. But for Simon and others dealing with the onslaught, that was welcome. “It was a terrible, strange, horrible period,” Simon says now. But for the most part, I — and many of his colleagues — didn’t really know. “People didn’t talk about their personal lives at work,” he says. “I didn’t talk about people I knew who I was visiting in the hospital at weekends.”

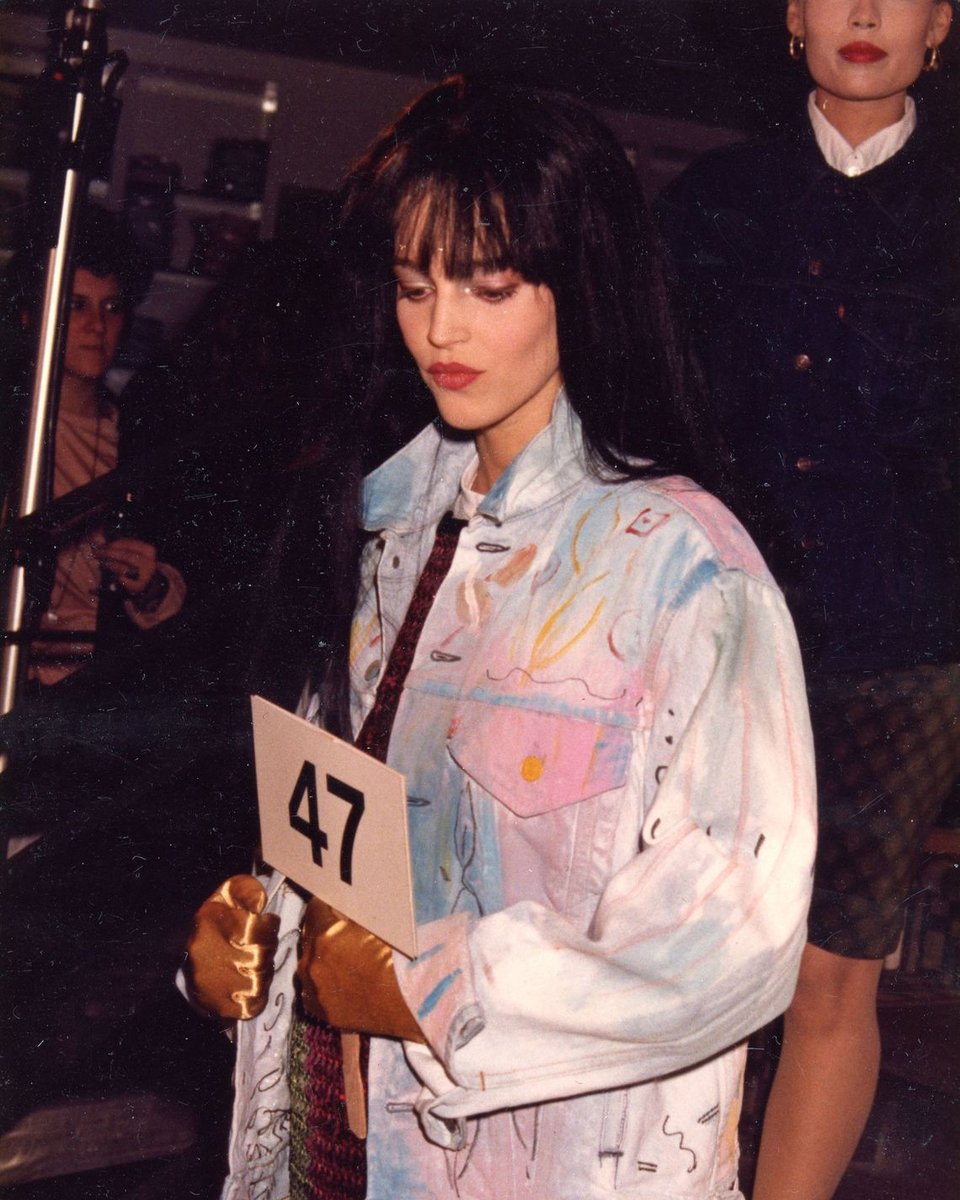

It was Simon who came up with the idea to partner with St. Vincent’s. We’d do a fashion show and auction the clothes, but what should they be? It had to be something anyone could wear and everyone could appreciate. We hit on a perfect piece of American sportswear, the Levi’s jean jacket. I called up the Haas family in San Francisco, the owners of Levi’s, and got them to donate the goods. Simon and Mallory Andrews and a brilliant woman named Anne Livet, who had her finger on the pulse of the art world, got many of our designers and the local artists who were Barneys’ new fans, to customize them. “Artists loved Barneys, and they wanted to participate,” Anne says. The great conceptual artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres — who himself succumbed to AIDS in 1996 — once declared “Barneys is my bodega,” at least according to his gallerist, Andrea Rosen.

Dianne Brill

Marla Hanson

A model wearing a Levi’s jacket designed by Willi Smith

Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Paloma Picasso, Robert Rauschenberg, and Kenny Scharf all did jackets. So did Azzedine, Karl Lagerfeld, Jean Paul Gaultier, Yves Saint Laurent, and Hermès. We called in friends and favors to book models. Madonna. Iman. Paulina Porizkova. Fran Lebowitz. Debbie Harry of Blondie and Kate Pierson of the B-52’s. Nightclub “It” girls like Edwige and Dianne Brill. Nobody was paid. They came, they put on the jackets, and they did their turn down Andrée Putman’s centerpiece staircase, christening it right. They held up little numbered placards, like they would have at a couture salon presentation by Saint Laurent.

That event, held in November 1986, was the biggest one at Barneys to date. Eight hundred people crammed in: artists and friends and designers, socialites, money types like Levi’s executive chairman Walter Haas. The models — nearly a hundred of them — came down the stairs high-kicking or shimmying or, in the case of Joey Arias, slithering on his stomach. There was even a little diva-off, when Madonna swerved in front of Iman just as she was preparing to do her walk. “The show was good,” Andy Warhol told his diary. “Great jackets. Good ideas. Everybody was in the show — Joey Arias and John Sex and the girl with the shape, Dianne Brill, and Teresa Scharf.” He took a photo with some nuns.

It was an emotional night. “There were many people like myself who were dealing firsthand with the AIDS epidemic, and we didn’t bring it to work,” Simon says now. But we had. Sister Patrice Murphy, a saint twice over — a nurse and a nun — who coordinated St. Vincent’s hospice program for AIDS patients, came to answer questions. Madonna brought her friend and former roommate, Martin Burgoyne, a young English guy I had seen around before — he’d been a bartender for Steve at Studio. He came to the Barneys event with the telltale lesions of KS. Madonna wore the jacket he designed for the show, and aside from her turn down the stairs, didn’t leave his side the entire night. It was a show of solidarity and support at a time of great fear and uncertainty — our own downtown version of what the world would see the next year, when Princess Diana was photographed shaking hands with an AIDS patient. Burgoyne didn’t even survive the month. He died on November 30, all of 24 years old.

I don’t mean to say it was only a sad event. In the face of it all, you had to insist on living, on having fun. And so we did. Get all those people in one room — probably around half of whom actually paid for their hundred-dollar tickets and half of whom crashed — and there are going to be some laughs, probably some tears. I think there were both for the evening’s most shocking moment: when John Galliano, drunk as a lord, took exception to Kate Pierson’s giant, tomato-shaped, John Waters–looking wig and leapt at her to rip it off her head. (The Cut, New York Magazine)

Elon Musk Has His Vision. Waymo Chief Tekedra Mawakana Says She’s Got a Better One

The Georgia-raised Silicon Valley tech exec, whom one venture capitalist calls “the un-Elon,” is gearing her car company up for a cross-country drive.

Tekedra Mawakana won’t take the bait, no matter how many times I try. The co-CEO of Waymo, which operates the biggest fleet of driverless cars in the country, is rolling through the streets of downtown San Francisco with me in a modified Jaguar I-Pace. Elon Musk has claimed he’s coming to take down Waymo and its more than 1,500 robotaxis with competing Teslas that can operate in “Full Self-Driving” mode—beginning with a 20-vehicle invite-only autonomous taxi service that’s started testing in parts of Austin. In 2019 Musk pledged to have a million Tesla robotaxis in service by 2020. So far, the Austin experiment hasn’t exactly been flawless. Can you believe he’s trying this again? I pepper Mawakana in the back of the Jag. When his “self-driving” cars need a human in the seat to keep from crashing? “I don’t know,” she half-whispers, looking out the window. She lets out a quiet challenge to Musk, even as she makes it a point not to say his name. “There’s zero evidence of anything. And there’s so much talk about it. We have a whole service across many cities, right? It’s not a play to have fanboys. It’s a play to, like, actually change people’s lives.”

Waymo and Tesla are in the same game, at least from this angle. Mawakana’s company has built an autonomous driver, made of a suite of sensors and software, that can be used in vehicles from multiple car companies; Musk has said that if his cars can’t drive themselves, Tesla is “worth basically zero.” Each is using robotaxis as proof of concept. The similarities end there.

Mawakana, like the business she helps lead, is deliberate, strategic, focused, cautious. Waymo is her one and only company, and she shares the leadership duties. Musk is Musk. Mawakana is a safety obsessive, as is Waymo. Musk is emblematic of the move-fast-and-break-things ideology. While Full Self-Driving Teslas have killed multiple people, Waymo vehicles have not killed a single person. Musk is apparently convinced that all Teslas need to drive themselves are advanced cameras and the right amount of AI. His cars start at $42,000; hers, outfitted with 29 of those cameras plus advanced radar, laser range finders, and acoustic sensors, can cost seven times as much. She’s a lawyer by training and spent much of her career at the nexus of government and technology. Musk, in fairness, also spent time at the nexus of government and technology—130 rocky days. She’s one of a handful of Black female (or Black, or female) chief executives in Silicon Valley; he goes on his social media platform to whine about how “teachers in California spend their time indoctrinating kids in DEI racism & sexism & communism.” It’s hard to imagine Musk on skates (though he appears to be making good on his promise to build a “roller skates & rock restaurant” in Los Angeles). Mawakana says, “I can be found with roller skates and a beach tent in my trunk at all times.”

It sounds like a cute study in contrast. Except the future of the global automotive industry—and how we move through cities—could be at stake, depending on which CEO’s vision wins out. Tesla is by far the bigger company, with annual revenue of almost $98 billion and about $7 billion in earnings, compared to an estimated $75 million in revenue and an estimated $1.12 billion in losses last year for Waymo. Mawakana doesn’t have great answers for how many jobs her autonomous vehicles might eventually cost (opponents say it could be millions), or how many people it currently takes to supervise her self-driving fleet (her deputies will only talk about the “minutes of human time” needed for each hour on the road), or the resilience of that fleet when protesters start lighting her robocars on fire (in Los Angeles last June). But when it comes to autonomy, Mawakana is ahead. Waymo is logging at least 250,000 driverless paid rides per week in Austin, Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Silicon Valley, more than 10 million such rides overall. Waymo had expanded its operations to Atlanta on the day Mawakana and I rolled through San Francisco together. Miami and DC are next, and Waymo has begun preparation for New York City.

“She believes the technology should speak for itself, in customers’ hands, as opposed to telling customers what to believe about the future,” says Alex Roy, a general partner at New Industry Venture Capital and a former executive at Argo, the Ford-backed autonomy company. “That’s why I call her the un-Elon.”

Mawakana lives a low-key life, at least by Silicon Valley mogul standards. She wasn’t invited to the Gilded Age Bezos wedding in Venice. She doesn’t bowhunt with Zuck, and she’s not joining Sam Altman in his doomsday structures. She lives in the same Bay Area home she bought when she was briefly a VP at eBay, in 2016 and 2017. Her art collection is modest, largely centered around Black and female artists, and is a “celebration of goddess energy.” She spends a chunk of her weekends going to her son’s basketball games; sometimes she’ll take him to Coachella or Rolling Loud. Vacations often involve a group of girlfriends sailing in the Caribbean or going to EDM festivals. Her big splurge last year was a quick trip to Paris for Vogue World.

I’ve been, for a long while, toiling away at this and pretty under the radar,” she says. “I genuinely have come to this through a very different path than most people and have arrived in it in a different capacity. And so, like, you know, it looks different” from the tech-CEO cliché.

Yet she and Waymo are now central to what is arguably the most important conversation happening in tech, and maybe our broader society too: how far can automated systems go and how much human labor will they replace. And it’s all happening while Mawakana fends off a challenge from the world’s richest man, leading the planet’s best-capitalized carmaker. What happens next?

“She believes the technology should speak for itself, as opposed to telling customers what to believe about the future. That’s why I call her the un-Elon.”

I meet Mawakana at Waymo’s nondescript offices on Market Street, in a bland tower that used to be the local headquarters of Chevron Oil. She’s dressed in black jeans and gold Air Jordans. Minutes into our chat, she recalls a moment and lets out a combination of a laugh and a groan. Her only kid recently turned 16 and just got his learner’s permit. So now the driverless-car CEO is teaching her son to drive, and “it’s really stressful to me. Waymos won’t be everywhere before he’s out in the world,” she says. About 40,000 Americans die every year in traffic accidents. Her son may be “super careful” on the road but that makes him kind of an anomaly. “People aren’t that great driving. People are speeding. People are talking on the phone. Their baby’s crying in the back seat. There’s a lot happening.”

Every erratic driver multiplies the complexity. The streetscape dials up the confusion: pop-up construction sites, traffic cops in the middle of the road, bikers, swerving scooter riders, potholes, buses, stop signs hidden by trees, club kids pouring out into the night, children running out to grab a lost ball. Making sense of it all—and then reacting to every chaotic element in fractions of a second—has proven to be one of the most challenging problems in computer vision and machine learning. The smartest minds in the profession thought they might be on the verge of solving it 20 years ago. They were wrong.

I was there in the Mojave Desert in 2004 when the Pentagon’s research arm, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, held a million-dollar contest to see which autonomous car could complete a 150-mile course the fastest. Only one made it just past seven miles. A Stanford professor named Sebastian Thrun tricked out a Volkswagen Touareg enough to complete the course the next year. Google tapped Thrun to help develop Google Street View and build an autonomous car for the masses, and that company eventually became Waymo. Every big automaker poured billions into similar projects, even as Waymo pivoted to making sensors and software that would go into other cars. By 2012, Google cofounder Sergey Brin said they’d be ready for the general public in less than five years. Tesla allegedly faked a video of Tesla’s self-driving capabilities to keep up. But Musk still confidently made his predictions, like autonomous cross-country Tesla trips by the end of 2017.

Mawakana would shake her head when she heard Musk talk like this. “Not a snowball’s chance in hell,” she remembers thinking back then. Despite the hype, Tesla’s Full Self-Driving program (and its predecessor, Autopilot) still required a human to take charge in times of trouble, making it closer to cruise control than true autonomy. Nor did Teslas have the array of sensors Waymos did: radar, to make sense of their surroundings in foul weather, and lidar, which relies on laser pulses, to “see” in the dark. And while Musk wanted his Teslas to be able to drive themselves anywhere, Waymo tried to constrain the problem by spending years mapping the streets of individual cities, starting in the Phoenix area. The company spent years more with Waymo-equipped vehicles driving themselves around those streets with humans behind the wheels to watch when and how the robocars screwed up. “It was when we removed the safety drivers that we realized in 2020 how much further we had to go,” she says. Every edge case and odd situation led to 10 more to figure out. She picks out one: “You hail the car. We know nothing about you. It’s a four-lane road that you’re standing in front of. We stop in the middle of the block across the street from you. And you’re vision-impaired. What do we do? How do you get to us?”

Fleet Street: Waymo's lot where the cars park themselves

It was too many variables for most of the big carmakers at too high a cost. One by one, they dropped their efforts to build their own mass-market autonomous vehicles. The few that remained began to face a human toll. Teslas running the company’s Autopilot system were involved in 736 crashes over four years, according to federal statistics. Seventeen were fatal. General Motors invested more than $10 billion in Cruise, which had been operating the largest robotaxi fleet in San Francisco. Then one of Cruise’s cars struck a pedestrian and dragged her underneath the vehicle for 20 feet. The outcry was deafening and only grew louder when the company was caught trying to hide details of the incident from federal regulators. GM shut down Cruise’s robotaxi operations in December.

Mawakana and Waymo have managed to avoid those nightmare scenarios so far. Part of that is by staying away from riskier rides: Mawakana and her co-CEO, Dmitri Dolgov, announced an end to an autonomous trucking program in the summer of 2023 to focus on commercial autonomous ride hailing, and two years later Waymo is close to allowing these self-driving cars on highways. Part of it is cultural: Waymo executives told me Mawakana has created an environment where they’re free to hit pause on major developments if they’re not sufficiently safe.

But a big part is technical. David Margines, Waymo’s director of product development, shows me a video of a recent almost-incident in December. A young girl falls off her scooter and into a two-lane road. The self-driving car smoothly moves clockwise around her. “What do humans do in situations like this? They either turn or they brake,” he tells me, drawing diagrams on a whiteboard. “When we were avoiding this, we had a half of a g of deceleration combined with a third of a g of turning at the same time.” It’s a different—and maybe better—way of driving.

On my trip with Mawakana around San Francisco, an older man in a floppy hat stepped out in front of the car right as we were rounding a corner near Telegraph Hill; the Jaguar stopped itself with plenty of space to spare. Downtown, when a fire truck was coming up fast in the left lane, the Jaguar quickly dipped from the middle to the far-right lane to give it maximum room.

How safe are Waymos, really? Depends on whom you ask, and how. Waymo boasts of having driven 71 million miles without a fatal accident. But the average for human drivers is about 1.2 fatalities per 100 million miles. The company claims its autonomous driver, compared to humans, has 88 percent fewer accidents that result in serious injuries. Research out of the University of California, Berkeley, suggests the robotaxis are about as safe as the average flesh-and-blood Uber driver. Outside safety researchers give Waymo credit for publishing peer-reviewed studies of its data; Tesla, for example, doesn’t do anything like it, and the data Musk’s company does release is debatable at best, these experts say. But the safety researchers I spoke with also contend that Waymo isn’t providing enough information to back up its safety claims. “They are seen as the most trustworthy player in the industry that is notorious for opacity,” says Carnegie Mellon University engineering professor Phil Koopman. “Their marketing, PR people have been claiming ‘saving lives’ for years now, and they do not have enough data to know whether that’s true.”

I’m the target market for a robocab. I didn’t get my license until I was 26, and that was after failing my first two driver’s tests. My skills behind the wheel, or lack thereof, are legendary in my family. With extensive practice, I can now parallel park—sometimes, if the space has been vacated by a school bus. So yes, I would love a robot chauffeur to take me around. But that comes with a cost.

Driving is one of the most common jobs in the country, especially for folks without a college degree. There’s something like 3 million full-time truck and delivery drivers, plus millions of more people driving Lyfts, Ubers, and old-school cabs. And while Waymo and other autonomous vehicle companies are concentrating on robotaxis right now, it’s clear that’s not the endgame. The endgame is replacing as many of those humans as possible with a Waymo driver—and to make your car robo-friendly too. The taxis are just a way to train the system. “Today, we’re deploying that in a Jaguar,” says Margines. “We’re going to do it with trucks someday, and we’ll do it on personally owned vehicles.” Which means whatever benefits autonomous driving brings—and I’m convinced there will be many—it will likely cost millions of people their livelihoods. “There’s not going to be driving jobs, and companies like Waymo don’t give a shit,” says Peter Finn, who heads Teamsters Local 856 in Northern California. The state Assembly has passed bills trying to keep a person in commercial vehicles, Finn adds, but Big Tech’s managed to prevent those bills from going anywhere. Waymo alone spent nearly $5 million on lobbying for various issues in California’s last legislative session.

Mawakana says she understands the anxiety. She grew up working-class, the daughter of an airman first class in the US Air Force, in Sandy Springs, north of Atlanta. Her uncle Joe Nathan was a truck driver in Mississippi. “It was a hard job. He ate in that truck, and he lived in the truck, and he died in that truck,” she says. But the best she can do to alleviate Finn’s concerns is to note that there has been a truck-driver shortage in recent years—and to riff about how the horse-and-buggy economy eventually grew into a more vibrant one based around the automobile.

But there are downsides to that vision. “If you give everyone’s car like a robot chauffeur, it would actually have a horrible impact,” says Edward Niedermeyer, author of The Autopilot Effect, a forthcoming book on the Tesla-Waymo competition. “Most of traffic is caused by single-occupant vehicles. Private AVs [autonomous vehicles] would give people zero occupant vehicles. You’d send your car off to deliver stuff. Why would you park the car when it could just circle blocks endlessly and just create traffic.”

And while the company may say it is “optimistic about how autonomous driving technology will create demand for many new businesses and jobs over time,” for now maintaining Waymo’s current fleet takes fewer people than you might think. The company claims in a statement it “directly and indirectly supports 2,000+ jobs” in the city and county of San Francisco, but that figure includes jobs “that benefit from increased economic activity (e.g., retail, hospitality, entertainment).” I was expecting to see a crew of mechanics at the company’s depot on Toland Street. Instead there were just a handful of contractors, swapping out tires and plugging the vehicles into their electric charging stations. The cars mostly drove themselves around the facility and parked themselves when their human caretakers were done with them.

Waymo also has people working in call centers who can respond to riders’ questions and teams that monitor and can provide guidance to the robotaxis if they get stuck. Exactly how many of these “remote assistants” are doing this work, where they’re located, and how many cars each person supervises neither Mawakana nor anyone else at Waymo will say exactly. All they’ll note is that there are people both in the United States and “outside,” and that, for every hour of vehicle time in San Francisco, Waymo needs “only a few minutes of human time on average.” Tesla may be advertising for “teleoperation” jobs to “access and control” its supposedly self-driving cars. (An inherently unsafe proposition, experts tell me, because of the lag time involved.) But for Waymos in the United States, Mawakana and her team insist, there’s no off-site steering wheel or joystick for a human to drive the cars from afar.

In an earlier job, Mawakana was forced to sit on a far more important secret. US intelligence agencies were sucking up huge amounts of data from commercial internet services—and ordered the companies not to say a thing about it. Mawakana was about a month into a new job as deputy general counsel of Yahoo when Edward Snowden’s revelations about the security state’s subornment of Silicon Valley started to come out. “On that day, we couldn’t go out and say to our users, ‘This is what’s happening.’ Was against the law,” she recalls. “There was an entire ecosystem that was happening on the back end that consumers didn’t even know about.” The disconnect made her seriously uncomfortable. Eventually, she left for eBay, and then for Waymo in 2017.

She became the head of global policy. At many tech companies that can be an ancillary role, but policy is critical to Waymo’s expansion. If it couldn’t persuade local governments to let its autonomous cars onto their roads, if it couldn’t build some kind of community comfort with the idea of robots on the streets, Waymo had no business, no commercial future. “I remember going home from the interview and being like, Okay, this is ‘put your money where your mouth is,’ mama,” she tells me. By 2021 she was named co-CEO.

Tekedra Mawakana at the 2024 Breakthrough Prize ceremony with her partner, Antony Taylor.

That put her in rarified company. According to a 2024 report from the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, less than a quarter of American tech workers are women and less than 8 percent are Black. That hasn’t stopped a slew of MAGA-friendly executives from demanding more “masculine energy” in the workplace and trying to roll back the diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts of the Black Lives Matter era. “At every level of my career, I have been one of very few,” Mawakana says. So when Musk and his mates shout that DEI is so dangerous, “it’s like railing against a machine that didn’t yield a lot of results. What it did yield is more voices at the table, more opinions. More is great. It’s been great. It’s been wonderful. But it hasn’t been transformative. And it definitely hasn’t been status quo–threatening.”

Under Mawakana, Waymo stood up to a trade organization to make laws more robocar-friendly in state capitals. She got together with groups like Mothers Against Drunk Driving and the Foundation for Blind Children so they could help plead the case for Waymos. “They couldn’t take their seeing-eye dogs into Ubers and Lyfts without being discriminated against,” she recalls. “They didn’t feel comfortable with their 22-year-old daughter after a club.” Still, there was major pushback, especially in San Francisco, where the city attempted to sue state regulators for granting licenses for the robotaxis to operate (a state court rejected San Francisco’s legal challenge in January). But even the city attorney acknowledged that Waymo was a relatively “good actor” in the field.

This is the kind of tiptoeing approach that Tesla fans would ordinarily make fun of. Except Musk’s robotaxi rollout in Austin is more cautious still. The cars may not go out in inclement weather and they won’t operate downtown, at least not at first. Finally, these driverless cars will have, in addition to the teleoperators, a “Tesla safety monitor sitting in the right front passenger seat.” Musk is once again promising those million robocabs are coming soon. Perhaps this time he’ll be proven right. But for now, Alex Roy notes, “Tesla is literally deploying, like verbatim, the deployment strategy used by Waymo.” With one key difference: Mawakana has been doing this for years, and Musk is millions of miles behind her. (Vanity Fair)

Carrie Coon is again coming to Broadway.

Carrie Coon, aka Bertha Russell

Carrie Coon, the actress known to many for her role as Bertha Russell in “The Gilded Age,” is scheduled to star in the Broadway premiere of her husband, Tracy Letts’ play, "Bug" in a production at New York’s Manhattan Theater Club at the end of 2025.

"Bug" will begin performances on Wednesday, December 17, 2025, with opening night slated for Thursday, January 8, 2026, at Broadway's Samuel J. Friedman Theatre.

Coon will reprise her leading role as Agnes White, a waitress caught in a web of paranoia and delusion with a mysterious drifter, according to The New York Times.

This marks Coon's first return to Broadway since her 2012 debut in "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" where she earned a Tony nomination.