Sunday, July 30, 2023. Annette’s News Roundup.

I think the Roundup makes people feel not so alone.

To read an article excerpted in this Roundup, click on its blue title. Each “blue” article is hyperlinked so you can read the whole article.

Please feel free to share.

Invite at least one other person to subscribe today! buttondown.email/AnnettesNewsRoundup

_________________________

Joe is always busy.

My Administration succeeded in giving Medicare the power to negotiate drug prices, lowering costs and the deficit.

— President Biden (@POTUS) July 26, 2023

That’s Bidenomics in action. pic.twitter.com/iJtD95cpSq

There is a serious youth mental health crisis happening in this country.

— President Biden (@POTUS) July 29, 2023

That’s why we are investing $1 billion to help schools hire and train more mental health professionals across the country, and we’ll continue to take action to face the crisis together.

_________________________

Kamala is always busy.

I challenge the hypocrisy of Republican officials who claim to care about the health of women and children but remain silent on the crisis of maternal mortality. pic.twitter.com/nvLmzasQxy

— Vice President Kamala Harris (@VP) July 28, 2023

MAGA extremists dare to tell us what is in our own best interests.

— Kamala Harris (@KamalaHarris) July 28, 2023

Well, I trust the women of America to make decisions about their own bodies. pic.twitter.com/kT6iggw5Kw

While some want to take us back, we are moving America forward. pic.twitter.com/CPLpFze5Nj

— Vice President Kamala Harris (@VP) July 27, 2023

_________________________

What Iowans are made of.

Touch 👇 to watch Iowans and the Vice President.

WOW. This is what the media will never show you. Vice President Kamala Harris was in Iowa earlier. Full crowd. Uproarious applause. Standing ovation. Don’t let anyone tell you people aren’t energized by Kamala Harris. Incredible. pic.twitter.com/SV9POi9u5n

— Victor Shi (@Victorshi2020) July 28, 2023

Trump, Spared Attacks by Rivals in Iowa, Doesn’t Return the Favor.

Almost every one of former President Trump’s 13 rivals who attended the dinner declined to even mention the primary’s front-runner.

Candidate after candidate at an Iowa Republican dinner on Friday avoided so much as mentioning the dominant front-runner in the race, former President Donald J. Trump.

But when Mr. Trump took the stage after more than two hours of speeches by his lower-polling rivals, it took him less than three minutes to unleash his first direct attack of the night on his leading challenger, Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida.

Mr. Trump not only suggested that Mr. DeSantis was an “establishment globalist” but called him “DeSanctis,” which in Mr. Trump’s argot is short for the demeaning nickname DeSanctimonious and is so well-known that most attendees clearly got the reference. “I wouldn’t take a chance on that one,” Mr. Trump joked.

The crowd of more than 1,200, which had warmly welcomed Mr. DeSantis when he spoke earlier, laughed and applauded throughout Mr. Trump’s riffs.

In contrast, Mr. DeSantis hadn’t mentioned the former president at all. The one speaker who did criticize Mr. Trump at length, former Representative Will Hurd of Texas — who is far from contention and not expected to qualify for the first Republican debate next month — was booed as he left the stage.

The dinner served as yet another reminder of Mr. Trump’s hold over Republican voters, despite his loss in 2020, the party’s struggles in the 2022 midterms and the weighty criminal charges he faces.

Hosted by the Republican Party of Iowa, the event brought together 13 candidates for the nomination, from Mr. Trump to challengers like Mr. DeSantis, Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina and former Gov. Nikki Haley of South Carolina. Also appearing were former Vice President Mike Pence, the entrepreneur Vivek Ramaswamy and long shots such as the media commentator Larry Elder, who, in keeping with the general theme of the evening, referred to himself as a “Trump clone.”

Each candidate spoke for 10 minutes to attendees at an event center in Des Moines, with Mr. Trump the last to appear. Organizers had said they would cut off the microphone of anyone who went over the time limit.

They proved as good as their word when the evening’s second speaker, former Gov. Asa Hutchinson of Arkansas, breached the 10-minute mark and had to deliver the final words of his speech to a dead microphone with the country song “Only in America” playing loudly over him.

Before he was cut off, Mr. Hutchinson, who is polling at around 1 percent, also took a shot at the front-runner, saying, “You will be voting in Iowa while multiple criminal cases are pending against former President Trump.”

As the race takes shape five months ahead of the crucial Iowa caucuses, Mr. Trump is surging ahead of a fractured field of rivals who are largely reluctant to criticize him, cowed by his fiercely loyal base.

But Mr. Trump’s legal troubles could still provide an opening for one of his rivals. The former president has now been indicted twice, and major new charges were added to one of those cases on Thursday. He also is expected to face two additional criminal cases. So far, however, the charges against him have seemed to coalesce Republican voters around his candidacy At the dinner, Mr. Hurd, a former C.I.A. officer, most pointedly mentioned the charges, and he also contradicted Mr. Trump’s false assertion that he had won the 2020 election.

“One of the things we need in our elected leaders is for them to tell the truth, even if it’s unpopular,” Mr. Hurd said. “Donald Trump is not running to make America great again. Donald Trump is not running for president to represent the people that voted for him in 2016 or 2020. Donald Trump us running to stay out of prison.”

The vast majority of the crowd did not agree. Boos rang out, and some attendees clattered their silverware to drown him out, a stark illustration of the risks of going after the former president.

“Thank you, Will,” said the next speaker, Mayor Francis Suarez of Miami. “You just made it very easy for me.”

Still, some voters said they had appreciated Mr. Hurd’s willingness to walk into the lion’s den.

“I honestly think that it took a lot of courage to say what he said about Trump at the end of there,” said Caden Mohr, 19, an educator from Eagle Grove, Iowa, who is leaning toward supporting Mr. Trump.

But beyond that tense moment, even veiled references to Mr. Trump were rare.

In one instance, Mr. Pence, who served as Mr. Trump’s vice president but fell out with him — and his base — over the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol, warned voters to “resist the politics of personality and the siren song of populism unmoored from conservative values.”

If anyone is to stop Mr. Trump’s growing momentum, it may have to happen in Iowa, where Mr. Trump has feuded with the popular Gov. Kim Reynolds, a Republican who received a standing ovation when her name was mentioned by another speaker for the first time. Mr. Trump has also skipped events held by influential evangelical Christian leaders.

Mr. DeSantis, in particular, has sought to capture the state’s evangelical voting bloc, running to Mr. Trump’s right on social issues and hitting him on his past support for gay rights. After fund-raising struggles and staff layoffs, Mr. DeSantis chose to begin a “reset” of his campaign with an Iowa bus tour this week.

“We’re doing all 99 counties in Iowa,” Mr. DeSantis told the crowd, which gave him a deafening standing ovation as he concluded his remarks. “You’ve got to go meet the folks, so you’ll see me everywhere.”

But Mr. Trump continues to hold a commanding lead in Iowa polls. A recent survey by Fox Business showed him leading the field with 46 percent of the vote, followed by Mr. DeSantis at 16 percent and Mr. Scott at 11. This week, Mr. DeSantis and Mr. Scott tussled over how the history of slavery is taught in Florida schools, as Mr. Scott seeks to supplant Mr. DeSantis as the leading alternative to the former president.

Of the major Republican candidates, only Chris Christie, the former governor of New Jersey, declined to attend the G.O.P. dinner on Friday. Mr. Christie has said he is not competing in Iowa, pinning his hopes on New Hampshire and South Carolina.

Also appearing at the dinner were Gov. Doug Burgum of North Dakota, the pastor Ryan Binkley and the businessman Perry Johnson.

The crowd’s attention clearly drifted depending on the speaker.

When Mr. Johnson mounted the stage an hour into the dinner, dozens of attendees left their tables, presumably to visit the bar or use the bathroom.

One of the biggest standing ovations of the night was saved for Mr. Ramaswamy, a wealthy political newcomer who is campaigning aggressively in the early nominating states and on Friday promised that he stands for “revolution,” not reform.

Teresa and David Hoover, a married couple from Marshalltown, Iowa, emerged captivated by Mr. Ramaswamy, saying he had a unique message for reaching future generations.

“When we talk to our kids and our grandkids, he’s right on the money — they’re lost,” Ms. Hoover, 65, said. “They need to know what it means to be Americans again.”

After the speeches, the campaigns hosted guests in hospitality suites.

In Mr. DeSantis’s suite, staffers for his super PAC set up pyramids of cans of Bud Light, a company the governor has attacked for a marketing campaign that featured a transgender social media influencer.

The beers weren’t for drinking. Instead, guests were offered buckets of baseballs to hurl at them. (New York Times)

In one of the great all time burns, Trump walked on stage in Iowa to a song with the lyrics “One could end up going to prison.” Thank you to whoever did this. It will be played over and over.

— Tom Joseph (@TomJChicago) July 29, 2023

pic.twitter.com/DYpLJxtQMI

_________________________

Justice Alito suddenly has much to say. An interview.

Allito has decided to speak in defense of the highly unpopular Supreme Court, and himself. The WSJ has become his personal outlet.

Samuel Alito, the Supreme Court’s Plain-Spoken Defender.

The Supreme Court usually makes news by making decisions, and it’s done plenty of that lately. In its first two terms with a 6-3 conservative majority, the justices have revisited old precedents and established new ones on abortion, gun rights, racial discrimination, freedom of speech and religion, the power of unelected federal regulators and more.

By comparison with the previous eight decades or so, the court has frequently declined to defer to elite political opinion, and as a result it has made news in other ways. A draft abortion opinion was leaked to the press. An armed man was arrested outside the home of Justice Brett Kavanaugh and charged with attempted assassination. The justices have come under attack from President Biden (“this is not a normal court”) and Democratic lawmakers. Partisan journalists have tried to gin up “ethics” scandals and incite animus against disfavored justices.

“I marvel at all the nonsense that has been written about me in the last year,” Justice Samuel Alito says during an early July interview at the Journal’s New York offices. In the face of a political onslaught, he observes, “the traditional idea about how judges and justices should behave is they should be mute” and leave it to others, especially “the organized bar,” to defend them. “But that’s just not happening. And so at a certain point I’ve said to myself, nobody else is going to do this, so I have to defend myself.”

He does so with a candor that is refreshing and can be startling. He spoke with us on the record for four hours in two wide-ranging sessions, the first in April in his chambers at the court. In the interim, he wrote an op-ed for these pages responding in detail to a hit piece from ProPublica, a self-styled “independent, nonprofit newsroom that produces investigative journalism with moral force.” Many of the court’s critics claim to want more “transparency.” Their hostile reactions to our April interview and his June op-ed suggest—no surprise—that they’re really after ideologically congenial rulings, not to mention conformist press coverage.

Justice Alito, 73, was appointed in early 2006 and is now the second most senior associate justice. He has emerged as an important voice on the court with a distinctive interpretive method that is rooted in originalism and textualism—adherence to the text, respectively, of the Constitution and statutes—but in some ways more pragmatic than that of Justice Clarence Thomas or Neil Gorsuch.

“There are very serious differences” in how the six conservative justices approach cases, Justice Alito says. The simplest difference involves respect for precedent: Justice Thomas “gives less weight to stare decisis than a lot of other justices.” It is, “in its way, a virtue of his jurisprudence,” Justice Alito says. “He sticks to his guns.”

That’s why Justice Thomas writes many lone concurrences. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), he argued that “in future cases, we should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents,” including those involving same-sex marriage, contraception and consensual sodomy. Justice Alito’s majority opinion carefully distinguished those issues from abortion. Justice Thomas often disregards precedents with which he disagrees and follows his own route to the majority’s destination—to cite a recurring example, by relying on the 14th Amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause rather than the Due Process Clause. The disadvantage of this approach, Justice Alito says, “is that you drop out of the conversation, and . . . lose your ability to help to shape what comes next in the application of that rule.”

Justice Gorsuch has an ornery streak that has shown itself in cases involving Indian law, crime and discrimination. “He’s definitely not a consequentialist,” Justice Alito says of his colleague—meaning he is less concerned with the real-world effects of following his principles.

An example is Ramos v. Louisiana (2020), which overturned a pair of 1972 precedents and held that the Sixth Amendment’s right to a jury trial requires unanimity for a finding of guilt in state court. Every state but Louisiana and Oregon already required unanimous verdicts, but “Ramos potentially affected many, many criminal convictions that had been obtained . . . using nonunanimous jury verdicts, which had been specifically approved by the Supreme Court,” Justice Alito says. “Overruling those decisions had potentially vast consequences. . . . That was not a big factor in his analysis.”

As for Chief Justice John Roberts, “he puts a high premium on consensus. He rarely dissents.” He filed no outright dissenting opinions in the 2022-23 term and only one in 2021-22. He also “has expressed a very strong tendency to protect the prerogatives of the judiciary,” as in Bank Markazi v. Peterson (2016). The court upheld a law directing that Iranian assets targeted by successful plaintiffs in a specific terrorism case be seized to pay the judgment. The chief justice dissented against what he called an unacceptable intrusion on judicial power: “Hereafter, with this Court’s seal of approval, Congress can unabashedly pick the winners and losers in particular pending cases.”

On the liberal side of the court, by contrast, “I don’t see that there’s a difference in interpretive method,” Justice Alito says. Yet he emphasizes that “we don’t always line up 6-3, 5-4, the way some people tend to think. If you look at all the cases, there are cases where the lineup is unusual.” Chief Justice Roberts wrote two election-law decisions this term, Allen v. Milligan and Moore v. Harper, in which he was joined by the three liberals and Justice Kavanaugh, along with Justice Amy Coney Barrett in the latter case.

Another prime example is National Pork Producers Council v. Ross, which upheld a California law banning the sale of meat from pigs that are “confined in a cruel manner”—almost all of which is produced in other states. The council argued that the law violated the Dormant Commerce Clause, a doctrine that limits states’ authority to enact policies that burden interstate commerce.

Justice Alito, who agreed with that view, says “it’s no secret that Justice Thomas and Justice Gorsuch don’t think that there is such a thing as the Dormant Commerce Clause.” Justices Barrett, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan signed on to parts of Justice Gorsuch’s opinion, providing a majority that let the law stand.

“I have not joined Justice Thomas, Justice [Antonin] Scalia, Justice Gorsuch in saying we should get rid of the Dormant Commerce Clause,” Justice Alito says. “I’ve written this in the Tennessee wine case—that the Constitution surely was meant to contain some principle that prevents the balkanization of the economy. That was one of the main reasons for calling the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.”

He refers to his 7-2 ruling in Tennessee Wine and Spirits Retailers Assn. v. Thomas (2019). In dissent, Justices Gorsuch and Thomas cited the 21st Amendment, which repealed Prohibition and gave states broad authority to regulate alcohol. Justice Alito’s majority opinion treated that provision “as one part of a unified constitutional scheme,” within which the lawmakers who ratified the 21st Amendment understood that “the Commerce Clause did not permit the States to impose protectionist measures clothed as police-power regulations.”

That demonstrates a central feature of Justice Alito’s jurisprudence: its emphasis on historical context. “I think history often tells us what the Constitution means,” he says, “or at least it can tell us what the Constitution doesn’t mean.” His dissent in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) is a case in point. “It’s perfectly clear that nobody in 1868 thought that the 14th Amendment was going to protect the right to same-sex marriage,” he says. Before this century, “no society—even those that did not have a moral objection to same-sex conduct, like ancient Greece—had recognized same-sex marriage.” The first country to legalize it was the Netherlands, effective in 2001.

The same attention to history informs Justice Alito’s textualism. “I reject the idea that a statute should be interpreted simply by looking up the words in the dictionary and applying that mechanically,” he says. Justice Gorsuch did something like that in Bostock v. Clayton County (2020), in which the court held that Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which prohibits employment discrimination “because of . . . sex,” covers “sexual orientation and gender identity.”

Justice Gorsuch reasoned that because sex is essential to the definition of both categories, such discrimination is “because of” sex. But in 1964 homosexuality was subject to widespread disapprobation, and gender identity “hardly existed as a concept, even among professionals in the field,” as Justice Alito says. “When it’s very clear that the author of the text . . . cannot have meant something, then I don’t think we should adopt that interpretation, even if a purely semantic interpretation of the statute would lead you to a different result.”

Justice Alito’s respect for precedent has limits: “Some decisions—and I think that Roe and Casey fell in this category—are so egregiously wrong, so clearly wrong, that’s a very strong factor in support of overruling.” Those are the 1973 and 1992 abortion cases that Dobbs overturned, with Justice Alito writing for a majority of five. Chief Justice Roberts provided a sixth vote to uphold Mississippi’s 15-week abortion ban but urged “a more measured course” that would narrow the precedents while deferring the question of whether to overturn them altogether.

Justice Alito has been known to take a similarly incremental approach. His opinion for the court in Janus v. Afscme (2018) held that compelling public employees to pay union dues violated the First Amendment, and it overturned a 1977 precedent, Abood v. Detroit Board of Education. A foretaste came in Harris v. Quinn (2014), also written by Justice Alito, which subjected Abood to a withering critique but left it standing.

“The question how broad a decision should be—should we overrule a prior precedent when we really don’t have to in order to decide this case?—it’s a judgment call,” he says. “There can be reasons for deciding the case more narrowly. Maybe we’re not sure whether it should be overruled. Maybe we think it would be better if the issue were highlighted for others to address first—scholars, lower-court decisions. Maybe it’s a question of what a majority of the court is willing to go along with.”

That last contingency sometimes depends on events more than philosophy. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died in September 2020, and President Trump appointed Justice Barrett to succeed her. Had Ginsburg lived a few months longer, the chief justice’s tentative approach might have prevailed in Dobbs. Or perhaps the justices wouldn’t have taken the case.

In the 2023-24 term, the court will consider whether to overturn Chevron v. NRDC (1984), an increasingly disputed precedent that requires courts to defer to administrative agencies’ interpretations of ambiguous statutes. Justice Alito is careful not to state a position on Chevron, but he does make a pertinent broader point about precedent: “I’m not in favor of overruling important decisions just by pretending they don’t exist but refusing to say anything about them.”

He says that’s what his colleagues did last month in U.S. v. Texas, the term’s only case that had him alone in dissent. The court threw out Texas’ challenge to lax Biden administration immigration guidelines on the ground that the state lacked standing to challenge them in court. But Justice Alito says Texas’ claim of injury “was the same as—in fact, stronger than—that of Massachusetts in Massachusetts v. EPA,” a 2007 case that opened the door to federal regulation of greenhouse gases. “The court just hardly said a word about Massachusetts v. EPA.”

The Biden policies suspended all enforcement measures for certain categories of illegal aliens, despite statutory language to the contrary—a clear violation, in Justice Alito’s view, of the president’s express constitutional duty to ensure that the law be faithfully executed. How did all eight of his colleagues end up on the other side? “I have no idea,” he says. “I honestly don’t. Why did it turn out that way? Because it involves immigration? Because it’s vaguely connected to Trump? I don’t know. I don’t know what the explanation is.”

After the justices reconvene on the first Monday in October, they will continue making news in the usual way. Among the issues on the fall docket, along with the reconsideration of Chevron: whether South Carolina impermissibly gerrymandered its congressional districts by race, whether the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s funding scheme is unconstitutional, whether Congress can tax unrealized investment income, and whether someone subject to a domestic-violence restraining order can be deprived of his right to possess firearms. (Mr. Rivkin and a law partner, Andrew Grossman, represent the appellants in Moore v. U.S., the tax case.)

The attacks on the court are sure to keep coming as well. Last week the Senate Judiciary Committee voted along party lines to advance Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse’s Supreme Court Ethics, Recusal and Transparency Act, which purports to impose on the justices and their clerks regulations “at least as rigorous as the House and Senate disclosure rules.”

Justice Alito says he voluntarily follows disclosure statutes that apply to lower-court judges and executive-branch officials; so do the other justices. But he notes that “Congress did not create the Supreme Court”—the Constitution did. “I know this is a controversial view, but I’m willing to say it,” he says. “No provision in the Constitution gives them the authority to regulate the Supreme Court—period.”

Do the other justices agree? “I don’t know that any of my colleagues have spoken about it publicly, so I don’t think I should say. But I think it is something we have all thought about.”

The political branches have other weapons they could deploy against the court. The Constitution doesn’t specify the number of justices, so Congress could pack the court by enacting legislation to expand its size. Last week a pair of leftist law professors issued an “open letter” urging President Biden to “restrain MAGA justices” by applying their rulings as narrowly as possible. The day the court decided Biden v. Nebraska, striking down Mr. Biden’s student-loan forgiveness plan, the president announced that he was undertaking legally questionable alternatives.

Justice Alito wonders if outright defiance may be in the offing for the first time since the aftermath of Brown v. Board of Education (1954): “If we’re viewed as illegitimate, then disregard of our decisions becomes more acceptable and more popular. So you can have a revival of the massive resistance that occurred in the South after Brown.”

Will the justices’ recent rulings endure? The court shows little sign of yielding to external pressure, but its three liberal members stand ready to overturn many recent precedents from which they dissented. Whether they’ll have the opportunity likely depends on who holds the White House and the Senate when future high-court vacancies arise. About that prospect, Justice Alito demurs: “We are very bad political pundits.”

(The interviewers are David B Rivkin, Jr. Who practices appellate and constitutional law and James Taranto who is the Wall Street Journal’s editorial features editor. This appeared in the Journal.)

_________________________

The Upper West Side has a renovated Barnes & Noble. Don’t you wish you had one too?

That Cool New Bookstore? It’s a Barnes & Noble.

NEW YORK—Barnes & Noble was once the enemy of independent bookstores. Now it’s trying to be more like them. And no place better explains the improbable reinvention of the biggest American bookstore chain than the Barnes & Noble on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

That shop in one of the world’s greatest book markets has been a battleground since the day it opened three decades ago. It might be the most iconic of the chain’s 596 locations: It’s the store that helped inspire the mega-store run by Tom Hanks’s character in the classic romantic comedy “You’ve Got Mail.”

It also has been the site of a grand experiment for much of the past year. The chain invested millions of dollars to rebuild this Barnes & Noble into a model for its other stores to emulate as the company transforms into a bookseller for the modern age.

“You don’t want to go too crazy in a Barnes & Noble because one of the joys of this store is that everybody comes in here,” said James Daunt, the chief executive since the company was taken private in 2019. “But do I think this can be a really interesting bookstore that is much, much more interesting than it currently is? Oh my goodness, yes.”

He would know. Daunt was a respected independent bookseller in London before he found himself running chains in both the U.K. and U.S. He was exactly the sort of person who could make Barnes & Noble interesting.

His plan to save the company and its bookstores is to combine the power of a big chain with the pleasure of a beloved indie. By shifting control of the process to individual store managers across the country, Daunt is giving local booksellers permission to do things they were never able to do before. They have discretion over purchasing, placement and even pricing. He wants Barnes & Noble locations to feel welcoming but not overwhelming—a chain store should be more inviting and less intimidating than a truly independent shop—and that means he needs the people who run them to make sensible decisions for their markets. “It’s only inexcusable if it’s not interesting,” he said.

Cash registers and magazines have been moved away from the front of the Upper West Side Barnes & Noble to make way for more books.

Cash registers and magazines have been moved away from the front of the Upper West Side Barnes & Noble to make way for more books.

The Barnes & Noble on the Upper West Side was incoherent the first time he showed me around last winter. It was cold and dreary outside and felt that way inside, where he was trying to make sense of an odd assortment of books. Viola Davis’s memoir was next to Franz Kafka’s diaries. Judd Apatow’s comedy interviews sat near a spiritual biography of George H.W. Bush. John le Carré was inches from Geena Davis.

I thought Daunt might pull the books off the shelf and rearrange them himself, but the whole point of his approach is that the CEO shouldn’t be the one making those calls. A bookstore exists to serve readers—not publishers, not investors and definitely not the bloke running Barnes & Noble.

Barnes & Noble used scale and uniformity to its benefit in the 1990s and 2000s, but those advantages have since become liabilities. Bookstores don’t have to be the same from one to another. They shouldn’t be, either. The best managers know the books they sell and the customers who buy them—and what works on the Upper West Side might not work in West Des Moines.

The idea behind the new Barnes & Noble is to make the national chain more like a collection of 596 local indies. The famous one in my neighborhood used to symbolize the company’s past. Now it offers a peek at its future. “If we can do it here,” Daunt said, “we can do it anywhere.”

Daunt agreed to give me before-and-after tours of the Upper West Side turnaround project, so we met in January and made plans to return when the shop was ready. By the time we met again in June, the vision he described had come to life.

The major renovation was necessary because the mission of bookstores has changed since this one opened in 1993. Back then, someone who wanted a specific book would visit their favorite brick-and-mortar store. Now anyone in need of that book probably visits Amazon.

This profound shift in consumer behavior prompted Barnes & Noble to reconsider the very purpose of a Barnes & Noble.

A physical bookstore competing against a $1.4 trillion online everything store must give people the stuff they know they want and the stuff they didn’t know they wanted.

“We’re here to help people browse,” Daunt said.

But first the Upper West Side location had to be a place where people wanted to spend time browsing. The bleak floor tiles were ripped out for sleek light wood. The drab carpet in that dumpy forest green was replaced with something less ’90s. The repainted walls were warmed up with splashes of pink. The space was designed to be cozier and brighter—and to keep you wandering around.

The most important change is apparent from the moment you step inside. The cash registers in the front of the store were shoved to the back. The magazines inexplicably occupying prime real estate on the ground floor were stuffed upstairs next to the relocated cafe. They had to be moved to make space for more books.

A lot more books.

Daunt has his own ideas about how books should be displayed, but he wants local managers to have ultimate authority. ‘It’s only inexcusable if it’s not interesting,’ he says.

Daunt has his own ideas about how books should be displayed, but he wants local managers to have ultimate authority. ‘It’s only inexcusable if it’s not interesting,’ he says.

You’ve got a new bookstore

James Daunt already had a job when he became the CEO of Barnes & Noble. In fact, he had two.

He got his start in the business in 1990, when he founded Daunt Books, a London indie known for its impeccable taste. His sublime boutique eventually became a group of nine shops across England that he still oversees. Then he surprised the industry by taking the top job at Waterstones, the Barnes & Noble of the U.K. After inheriting a troubled chain with roughly 300 stores in 2011, he nursed a company bleeding money back to profitability. Waterstones was bought in 2018 by the activist hedge fund Elliott Management, which kept Daunt in charge and took aim at Barnes & Noble itself.

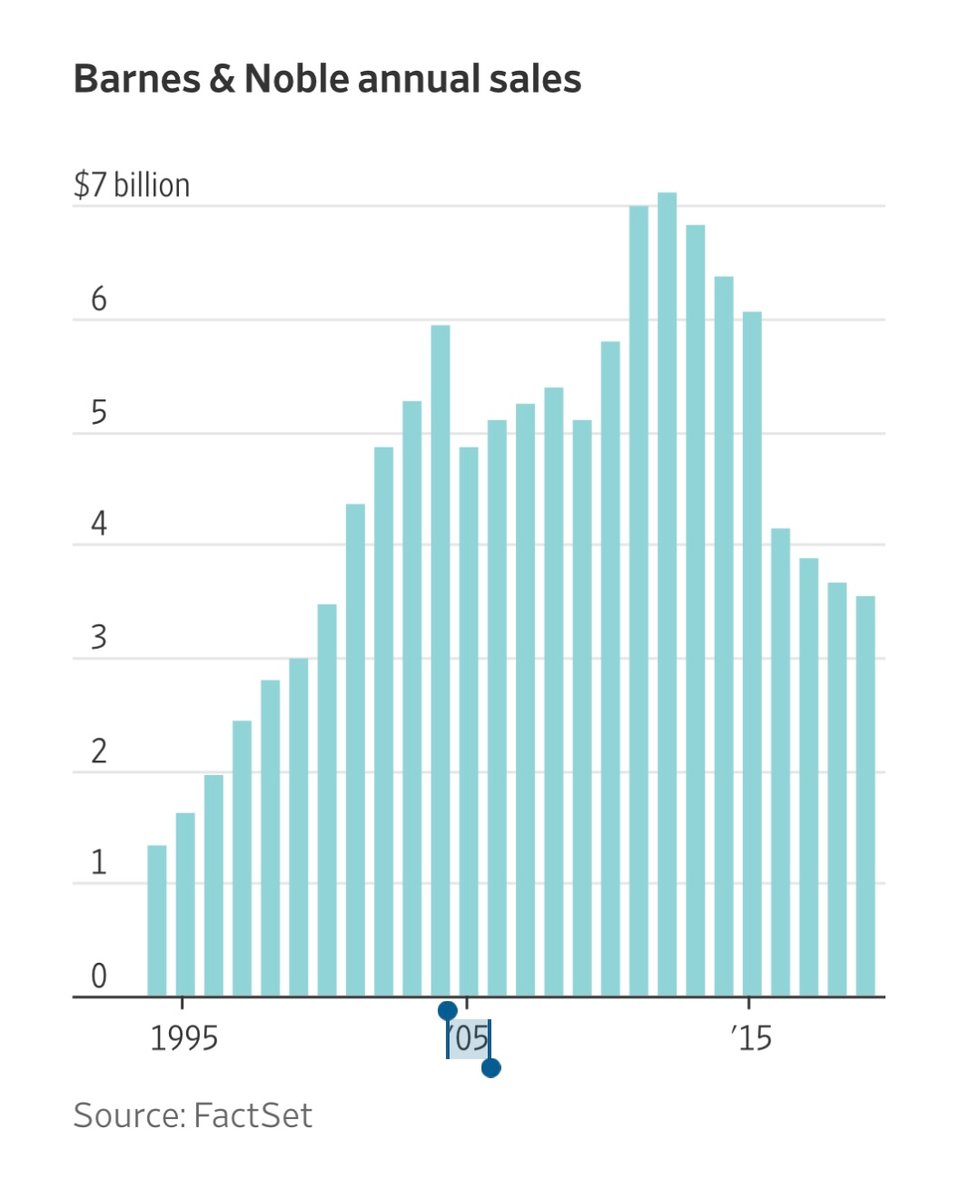

The poorly managed chain was ripe for a takeover after cycling through CEOs and losing half of its annual revenue even after its rival Borders failed. Elliott paid $475 million in the deal and tapped Daunt to lead another unlikely comeback.

Daunt, 59, speaks quietly, as if he were in a library, but the insight at the heart of his management philosophy is worth screaming from the rooftops: find people who are passionate about books and let them sell books as they see fit. This sounds rather obvious when he says it. But entrusting a chain to someone who not long ago was running a posh store in Central London was a radical act of corporate desperation.

“I think it had to almost die before anyone was prepared to risk that,” Daunt said as we strolled around the Barnes & Noble on the Upper West Side. “It’s no coincidence that I took over Waterstones when it died and I took over this place when it was barely breathing.”

One way to measure the health of a bookstore is the return rate—the percentage of unsold books that retailers ship back to publishers. The lower, the better.

Waterstones and Barnes & Noble both had return rates between 20% and 25% when he started. It’s down to 3.5% at Waterstones. Barnes & Noble’s is 9%, Daunt said. His target is 5%.

At the remodeled Barnes & Noble, rows of books became rooms of books.

At the remodeled Barnes & Noble, rows of books became rooms of books.

Display tables are organized in clever ways that transcend algorithmic recommendations.

Display tables are organized in clever ways that transcend algorithmic recommendations.

Not everyone is thrilled about his plans to make Barnes & Noble a more efficient business, which publishers fear will translate into the nation’s largest chain purchasing fewer books. The managers of individual stores having more control over what they stock and how they price it means the publishers have less. Others in publishing are skeptical that local tastes matter as much in a business increasingly driven by national bestsellers.

Daunt was hired by Barnes & Noble right before U.S. bookstore sales bottomed out. They declined every year from 2008 to 2019 and cratered in 2020, according to federal data. But retailers have proven surprisingly resilient since the first year of the pandemic. Sales rebounded in 2021. They continued upward in 2022. They’re on pace to increase again in 2023.

As a privately held company, Barnes & Noble doesn’t report financial results, but it’s clear that it’s no longer near death. While the number of locations has decreased 5% since the acquisition, the chain is now expanding and plans to open 45 stores this year, including some that closed and reopened with smaller footprints, like one on the Upper East Side that opened this month to a line around the block. It’s also giving facelifts to existing shops across the country. But not every store needs a complete makeover to feel refreshed. I recently popped into a Barnes & Noble off the interstate in Pueblo, Colo., where even subtle tweaks made for a delightful browsing experience.

Daunt chose to salvage the Upper West Side shop with a $4 million renovation, the same cost as opening a new store of this size, because he felt the building itself was beautiful and the location on Broadway was ideal. He also thought the chain needed a strong presence in this bookish stretch of Manhattan. Coming from London, where there are several dozen Waterstones locations, he was dismayed to find only seven Barnes & Nobles in his “extraordinarily un-bookstored” new city.

“That’s not because New Yorkers don’t buy books,” he said. “It’s because the bookstores went out of business.”

Even the bookstores in movies couldn’t afford to stay in business. In the 1998 rom-com “You’ve Got Mail,” Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan play rival Upper West Side booksellers Joe Fox and Kathleen Kelly, and she closes the Shop Around the Corner when his Fox & Sons Books chain opens down the street and promises “cheap books and legal, addictive stimulants.”

In 1998’s ‘You’ve Got Mail,’ Tom Hanks played an executive running a chain modeled on Barnes & Noble. Meg Ryan played an independent rival driven out of business by Hanks.

In 1998’s ‘You’ve Got Mail,’ Tom Hanks played an executive running a chain modeled on Barnes & Noble. Meg Ryan played an independent rival driven out of business by Hanks.

The movie was partly based on Barnes & Noble invading the neighborhood and the real-life drama that ensued. The company had a higher market value than Amazon around the time “You’ve Got Mail” hit theaters, but that was 25 years and trillions of dollars ago. It’s quaint to think of a bookstore with an espresso bar as the villainous corporate bully now that Amazon is so big it makes Walmartlook small.

Every bookstore these days is the Shop Around the Corner—even a Fox Books superstore.

Of course, there are genuine indies thriving in New York today, exquisite shops like McNally Jackson and Books Are Magic and institutions with loyal customers like the Strand. They exude an ineffable charm that is almost impossible to replicate.

“An indie bookstore is always going to have that idiosyncratic, owner-operated feeling that you’re not going to get in a chain store,” said Dane Neller, the CEO of Shakespeare & Co. in New York. “You’re just not.”

Daunt happens to agree. As someone who can relate to both Joe Fox and Kathleen Kelly, he is uniquely qualified to compare indies and chains, even though he confessed to not having seen “You’ve Got Mail” until after we met. He told me Daunt Books is simply different from a Barnes & Noble—and there is a place for both. “A large store like this will always be much more and much less,” he said. But just because it’s not the same doesn’t mean it can’t be similar. “Within a chain,” he said, “you can create an awful lot of the ethos of an independent bookstore.”

The business strategy isn’t the only part of Barnes & Noble that is evolving under Daunt. So is the goal of every bookstore.

“To come in and enjoy yourself,” he said. “As opposed to effectively the raison d’être at the moment, which is to rack these books up in a way that you can find them, and then you find the book you want and leave. That’s a big old shift.”

‘I didn’t realize how bored I was’

One day this summer, Daunt was stumped. He was talking about the device that instructed Barnes & Noble’s staffers where to put each book on every shelf but couldn’t remember its name. He asked a young employee arranging hardcover fiction in the Upper West Side shop for help. She told him it was called a PDT—a portable data terminal. Then she explained that the store’s 30 booksellers weren’t really working with PDTs anymore. They were using their brains instead of following the beep-beep-beep of a scanner. He thanked her and walked away.

“She has no idea who I am,” Daunt whispered.

The CEO of Barnes & Noble was standing in the front of a busy store that was completely unrecognizable from six months earlier.

He was surrounded by books.

There were 87,756 in stock on a recent day, including 2,000 titles on the ground floor alone, which Daunt estimated to be “a ton more” than before. There were piles of bestselling fiction, nonfiction and mysteries. There were popular cookbooks and children’s books hugging the columns where shoppers naturally gravitate. There was an upstairs level that stretched across the building on a full city block. And there was still an entire wall of bare shelves waiting to be lined. “We need more books,” said Victoria Harty, the assistant store manager.

But swarming Barnes & Noble shoppers with books wasn’t enough. The books themselves also had to be optimized for discovery. Many covers face outward instead of spines. Handwritten staff picks float off shelves. Neatly curated tables are organized in clever ways that transcend algorithmic recommendations.

It had been grueling to keep the store open during construction, but the booksellers could see the results of that work in this humming store, even if it wasn’t nearly done yet. “There’s a thousand little things that need doing,” said Jason Byrnes, the store’s manager.

Assistant Manager Victoria Harty and Manager Jason Byrnes at the Upper West Side Barnes & Noble.

Assistant Manager Victoria Harty and Manager Jason Byrnes at the Upper West Side Barnes & Noble.

Byrnes went to elementary school in the neighborhood, so this was his childhood bookstore long before it was his office. After working in other Barnes & Nobles around Manhattan and Brooklyn, he was recruited back to the one where he grew up. Daunt said the store’s former manager oversaw the initial phase of the construction so well that he moved her into a new role handling those projects elsewhere. To fill the vacancy, he looked for talented booksellers with local knowledge and skills that would fit well together, and he found people like Harty and Byrnes. It turned out having the authority to make their own decisions was more stimulating, gratifying and way more fun than taking orders from a machine.

“I didn’t realize how bored I was,” Byrnes said.

To run hundreds of stores the way he runs the one with his name, Daunt needs to recruit more full-time employees and pay them to stick around. They won’t become model booksellers overnight. Many won’t be booksellers forever. But most can grow to be great at one part of the job and show their peers at nearby stores how they do it. The person studying data to order books at one Barnes & Noble in Atlanta can train inventory specialists at other stores in the area more effectively than an executive from corporate headquarters. It’s a brilliant formula when it works: Daunt likes to say that the less he does, the smarter he looks.

But to look around a Barnes & Noble with him is to see the questions worth thinking about in every nook of the bookstore. What is the optimal table density? Does “Life” by Keith Richards belong with other memoirs or music books about the Rolling Stones? How should the history section be arranged?

There’s not always a right answer. But there are wrong answers. It baffles Daunt that 20% of the chain’s locations sort history books alphabetically by author. “This was a store that had history arranged A-to-Z,” he said last month. “Now it’s chronological.”

A bookstore should be intuitive enough for a child to navigate but compelling enough that adults don’t mind getting lost. Because this one has an eccentric layout over 28,000 square feet—books on two floors, gifts and toys on the mezzanine—Byrnes and his team made it a priority to improve the flow. They reconfigured the map based on customer feedback. On the upstairs level, where toddlers run around and teens flirt after school, they moved entire sections around. “Then moved them again and moved them again,” he said. Rows of books became rooms of books. Displays on the side of bookcases were treated like vertical tables. Shelves grew two rows taller to “reclaim the air” without reducing inventory, Daunt said.

There were another thousand little things that still needed to be done—and those small details would turn into something much bigger. Daunt has learned from his decades of experience that there is a direct correlation between how a bookstore looks and how it performs.

“It’s really peculiar if good bookstores don’t sell more books,” he said. “They always do in the end.”

The real question is how many more. Daunt expects this Barnes & Noble’s sales to double from their 2019 levels by 2026.

But the remodeled store is already seeing a sales uptick because of the shrewd decisions of its booksellers. By the front door is a table of literary historical fiction that includes “The Weight of Ink” by Rachel Kadish and “People of the Book” by Geraldine Brooks, paperbacks that had been hiding upstairs because they were published several years ago. Harty moved them downstairs. She knew they would interest highbrow Jewish readers on the Upper West Side more than the median shopper in the average market. She was right. They went from selling one copy a month to 20.

“One of the first things we did when we first got here was to start building the tables,” Byrnes said. “To watch the titles we brought in consistently show up as our top-selling books was very satisfying.”

Daunt and I were standing by that table last month when a shopper walked past us with a Daunt Books tote bag—the ultimate sign that something unexpected is happening at Barnes & Noble.

“We’re giving them what I think they recognize as a really good bookstore,” Daunt said.

But I was curious for one more opinion of the Barnes & Noble on the Upper West Side. So a few weeks ago, I emailed Joe Fox himself: Tom Hanks.

As it happens, Hollywood’s most famous bibliophile recently published his first novel, which is featured on its own table in this chain bookstore that’s beginning to feel like an indie.

“I’ve never been in the newly transformed B&N,” Hanks wrote, “but I approve the concept.”

(Wall Street Journal).

_________________________