Saturday, September 16, 2023. Annette’s News Roundup.

I think the Roundup makes people feel not so alone.

To read an article excerpted in this Roundup, click on its blue title. Each “blue” article is hyperlinked so you can read the whole article.

Please feel free to share.

Invite at least one other person to subscribe today! buttondown.email/AnnettesNewsRoundup

________________________________

Let’s look at “the news.” 3 posts.

Headlines and news reports all over the country feed the GOP agenda against Biden by Annette Niemtzow.

“Double blows of inquiry and son’s indictment create tough stretch for Biden.”

This 👆 was yesterday’s Washington Post headline on the Hunter Biden and fake impeachment charge situation. What will this implicit smear do to the President?

Remember there are comparable smears happening in newspaper and on media across America and we can expect more of the same until November 5, 2024.

These news outlets may see themselves as impartial agents but by keeping the subject of Hunter Biden and Biden’s impeachment front and center, they are serving the GOP. Notice that these issues hide other issues from taking the right place in voters’ minds… sample, Biden-Harris achievements, 91 Trump felony charges, GOP incompetence, etc.

Remember Kerry and the swift boat. Remember Hillary’s emails. Keeping negative issues alive with focus on candidates is dangerous and, yes, affects voters and elections.

_________

With democracy on the ballot, the mainstream press must change its ways.

US news organizations have turned Biden’s age into a scandal and continue to cover Trump as an entertaining side show.

Christiane Amanpour has reported all over the world, so she recognizes a democracy on the brink when she sees one.

Last week, as she celebrated her 40 years at CNN, she issued a challenge to her fellow journalists in the US by describing how she would cover US politics as a foreign correspondent.

Add to this the obsession with the “horse race” aspect of the campaign, and the profit-driven desire to increase the potential news audience to include Trump voters, and you’ve got the kind of problematic coverage discussed above.

It’s fearful, it’s defensive, it’s entertainment – and click-focused, and it’s mired in the washed-up practices of an earlier era.

The big solution?

Remember at all times what our core mission is: to communicate truthfully, keeping top of mind that we have a public service mission to inform the electorate and hold powerful people to account. If that’s our north star, as it should be, every editorial judgment will reflect that.

Headlines will include context, not just deliver political messaging. Overall politics coverage will reflect “not the odds, but the stakes”, as NYU’s Jay Rosen elegantly put it. Lies and liars won’t get a platform and a megaphone.

And media leaders will think hard about the big picture of what they are getting across to the public, and whether it is fair and truthful. Imagine if the New York Times, among others, had stopped and done a course correction on their over-the-top coverage of Clinton’s emails during the 2016 campaign. We might be living in a different world.

The Nobel-winning economist Paul Krugman pointed out last week that the media apparently has failed to communicate something that should be a huge asset for Biden: the US’s current “Goldilocks economy”. Inflation is low, unemployment is low and there’s virtually no hint of a recession. But many Americans, according to surveys, are convinced the economy is terrible.

Two-thirds of Americans are unhappy about the economy despite reports that inflation is easing and unemployment is close to a 50-year low, according to a new Harris poll for the Guardian. Many are unaware of, or – because of mistrust in the government or in the media – simply don’t believe the positive economic news.

“There’s a really profound and peculiar disconnect going on,” Krugman said on CNN.

Media coverage surely is partly to blame. When gas prices spike, it’s the end of the world. When they steady or fall, it’s the shrug heard ‘round the world. It illustrates one of journalism’s forever flaws – its bias for negative news and for conflict.

Can the mainstream press rise to the challenge over the next year?

“When one of our two political parties has become so extremist and anti-democratic”, the old ways of reporting don’t cut it, wrote the journalist Dan Froomkin in his excellent list of suggestions culled from respected historians and observers.

In fact, such both-sides-equal reporting “actively misinforms the public about the stakes of the coming election”.

The stakes really are enormously high. It’s our job to make sure that those potential consequences – not the horse race, not Biden’s age, not a scam impeachment – are front and center for US citizens before they go to the polls.

As Amanpour so aptly put it, be truthful, not neutral. (Margaret Sullivan, The Guardian).

_________

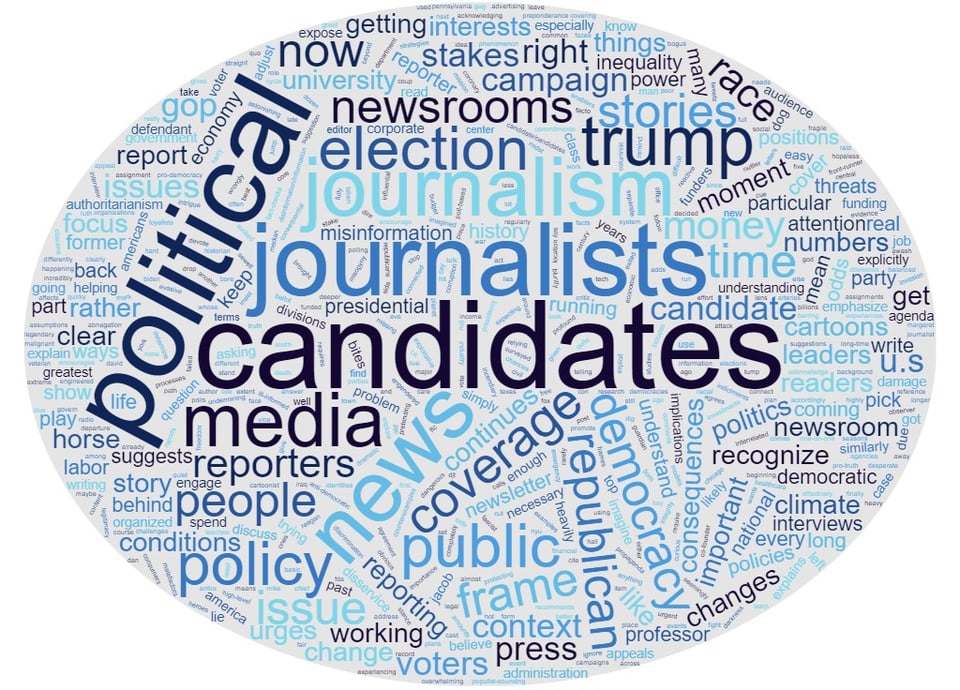

A desperate appeal to newsroom leaders on the eve of a chaos election | Press Watch

None of our newsroom leaders could possibly have imagined 10 years ago that fascist appeals to violence and racial hatred would be so common and effective, that the political discourse would be so awash in misinformation and disinformation, that homophobia and misogyny would make such a dramatic comeback, or that a con man who engineered a failed coup could be a front-runner for the presidency, posing a dire threat to the country’s future as a democracy.

But even as the nation faces another potentially cataclysmic election in 2024 — arguably the most perilous in American history — the mainstream news industry continues to engage in the same business-as-usual that got us here in the first place.

Maybe it’s time to change things up?

I write about this all the time on Press Watch. (Read my mission statement.) But for this piece, I decided to survey a few dozen experts — all of them critical readers of the news, many of them journalists – asking them for their suggestions of what our top newsrooms should do differently this time around.

Generally speaking, their answers are not radical. They are simply common sense.

Some call for changes that have been necessary for a long time and are now urgent — existentially so.

But some changes are specific to this moment when one of our two political parties has become so extremist and anti-democratic that both-sides reporting is no longer a safe harbor for political journalism. Indeed, it actively misinforms the public about the stakes of the coming election.

If you know someone in a leadership position in a major American newsroom, please send this to them and urge them to read it?

Pick the Right Frame

I’m increasingly persuaded that when it comes to political journalism, getting the frame right is as important as getting the facts straight. Whose terms are you using? What requires explanation and what doesn’t? What is normal and what is not?

Jennifer Mercieca, a historian of political rhetoric at Texas A&M University, proposes: “Use a ‘democracy frame’ instead of a horse race frame. What impact does the event/news item have on democracy in America?…

“So much policy is already decided by how political actors frame facts and events. It matters if we call the situation at the border a ‘humanitarian crisis’ or an ‘invasion’ or a ‘relief effort.’ News organizations should choose frames that humanize people and promote democracy.

“Promote democratic thinking through how you frame rather than allow your news organization to be used to frame things in non-democratic/authoritarian ways.”

Not the Odds But the Stakes

There was overwhelming agreement among the people I surveyed that newsroom leaders should cut back on horse race coverage in favor of news stories about how the different candidates and parties would govern.

Jay Rosen, a journalism professor at New York University and influential press critic has coined a phrase for that: “Not the odds but the stakes.”

He explains: ‘”Not the odds but the stakes’ is my shorthand for the organizing principle we most need from journalists covering the 2024 election. Not who has what chances of winning, but the consequences for our democracy. One implication of ‘stakes’ reporting is that it can draw on the knowledge and experience of reporters beyond those who are on the politics beat.”

Norman Ornstein, a veteran political observer, explains: “The preponderance of coverage of elections is always about horse race– who is up, who is down. (As an aside, often relying on bogus or squishy polls.) This is the easy way out. Elections have consequences, life and death ones and now a question of the life or death of the democracy. That ought to be the core of coverage in 2024.”

Victor Pickard, who teaches media studies at the University of Pennsylvania, suggests: “Instead of horse race coverage discuss the real-world implications of candidates’ policy proposals with concrete examples and counterexamples from U.S. history as well as from international contexts.”

Set the Agenda

The candidates too often serve as de facto assignment editors in our top newsrooms. They determine what the reporters write about. That’s a tremendous disservice to the public and a profound abnegation of the essential role of a free press.

Mark Jacob, a former Chicago Tribune editor turned freelance writer, urges newsrooms to “Create an agenda instead of being obedient to the candidates’ agendas. Pick an issue (Social Security, health care, etc.) and get clear policy positions from all the candidates. If a candidate refuses to answer or gives an evasive answer, call them out.”

Harry Shearer, the satirist who hosts “Le Show” on public radio, suggests: “Pick five ‘major issues’; devote a full week to both the issue and the candidates’ positions on the issue.

“Rather than waiting for a candidate/candidates to center attention on an issue, journalists should do the centering, and find comments in the public record relating to each issue. That is, journalism should be less passive and reactive, and more active.”

Parker Molloy, who critiques the media in her newsletter, The Present Age,advises: “You can do the quirky stories and palace intrigue stuff, you can talk about polling. You can absolutely do those things. But that needs to be secondary to helping readers understand what candidates believe, what they would do if elected, and what those policies would actually mean to the public.”

Focus on the Greatest Threats

There is no shortage of existential or near-existential issues that our newsrooms could and should make central to their 2024 coverage.

Climate change is arguably No. 1.

Edward Wasserman, a media ethicist and former dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at UC-Berkeley, notes: “Climate is the unrivaled problem of our time, and candidates must be challenged to show how they would exercise leadership in responding to it and developing policies, remedies or palliatives.”

The question should be: What are your plans to slow climate change and adjust to new conditions? Not: Do you think it’s a problem?

Trump’s attempt to steal the election is the most obvious of many indicators that a Republican victory in 2024 could damage or even end democracy as we know it.

Dean Baker, media critic and co-founder of the Center for Economic and Policy Research encourages a particular focus on one part of that threat: “Both the leading Republican presidential candidates have explicitly said they want to replace high-level civil servants with political cronies. This effectively means that we would have Trump/DeSantis loyalists running agencies like the FDA, FTC, Justice Department. The implications of this departure from a 150-year old system are more important than anything else in this race, but has gotten almost no attention.”

I’d put income inequality right up there as a dire issue and so would Wasserman, who writes: “Emphasize candidate positions that address inequality and insist that candidates who exploit social divisions also address inequality of wealth and income.”

Hamilton Nolan, a labor reporter for In These Times, urges newsroom leaders to “Put labor front and center. Explore how organized labor power can become political power. Report on what poor and working people need from politicians and not vice versa.”

And once they raise an issue, newsrooms need to keep at it.

Joanne Lipman, former chief content officer at Gannett, says: “Sustain coverage of important news events, don’t just drop them to jump on today’s latest hot takes.”

The Importance of Context

Lipman urges: “Provide context to news stories. Don’t just cover every event through the lens of left vs right.

“Journalists cover EVERY story through the lens of left vs right, which means news consumers don’t actually get real information about the issues. We are woefully ill-informed on basic topics. ‘Bidenomics’ has been quite successful, for example, but most people wrongly believe the economy is in the toilet. Our understanding of policies is even worse.”

James Fallows, a long-time reporter and editor who writes the newsletter Breaking the News, bluntly advises: “READ SOME GODDAMNED U.S. HISTORY. Almost every one of these arguments, divisions, solutions, and quandaries is part of the national past. And it’s necessary to explain this, when you realize that most Americans were born in 1985 or afterward (the median US age is now 38), so most US voters cast their first vote after the beginning of the Iraq war. Some of the clues need to be connected.”

Baker can’t stand it when people cite numbers that mean nothing to readers. “Put numbers in context. NO ONE has any idea what millions, billions, or trillions mean in the context of the federal budget or the U.S. economy. You are not conveying information if you just report these numbers without any context.”

What Not To Do

Ruth Ben-Ghiat, a historian at NYU who writes about authoritarianism, advises: “Do not treat Trump and GOP as conventional candidates, using ‘balanced’ coverage models suitable for democracies. Trump/GOP have exited democracy and are trying to take down America.”

Now that Tump and his allies have been charged in Georgia as part of a wide-ranging criminal enterprise, the coverage needs to reflect that, Ben-Ghiat says. “Take a cue from how organized crime is covered in terms of writing headlines, tweets, etc.”

“The live ‘town hall’ format should be completely abandoned,” writes Jacob. ” It makes it too easy for candidates to get away with lies or play to ringers in the audience. Better to do quiet one-on-ones. But in either case (one-on-one or town hall), record the interview and then splice in well-researched fact-checks before broadcasting.”

“Radically cut back on poll-based stories. Instead report more on location conditions,” writes Fallows. He continues: “For reporters: Resist writing ‘how will this play?’ stories. Instead write ‘how would this work?’ stories. (I.e. don’t imagine yourselves as unofficial campaign strategists. Imagine yourselves as proxies for a public that will be affected by taxes, investments, policy changes, etc.)

“The more reporters emphasize ‘how this will play,’ the more likely most Americans are to think ‘it’s all just a show.'”

“Stop getting sucked into culture war soundbites that are simply meant to inflame and get coverage,” says Lipman.

“Ignore incendiary assertions of cultural bigotry with no clear policy significance, recognizing that coverage rarely weakens support for malefactors,” says Wasserman.

And don’t give Trump so much attention. History professor and Letters from an American newsletter author Heather Cox Richardson writes: “It is astonishing how fully the Trump circus continues to absorb oxygen in the midst of the most consequential administration since at least Reagan. The press certain doesn’t have to cheerlead for the administration, but it should make clear the extent of the changes it’s overseeing.”

The Missing Voter Interviews

Richardson ponders: “We are still getting endless stories about the Republican voter. But who are the Democratic voters? What do they want? They are, after all, a majority.”

“Recognize that you can always find extremists who will say inflammatory things,” writes Fallows. “That’s become the ‘dog bites man’ story — so familiar and cliched it is of no use. Look also — not exclusively, but also — for ‘man bites dog,’ in the form of citizens and officials trying to find a reasonable path forward.”

Sewell Chan, editor of the Texas Tribune, urges reporters to engage in “deeper dive interviews with voters, that don’t start from ‘who are you supporting’ but rather from ‘what are you directly experiencing in your life, and how does that connect to what you want/don’t want from government?'”

Reporters should “actually spend time understanding the experiences, challenges, tradeoffs and dilemmas” that voters face, Chan writes.

(I agree, and have some exciting news forthcoming about a plan to do just that.)

Legendary journalist and documentarian Hedrick Smith wants newsrooms to focus on Republicans who want to put Trump behind them.

“Dig into the 49 percent of GOP primary voters who are NOT for Trump. Who are they? Where do they stand on key issues like immigration, the economy, racial discrimination, limits on tech, and the future of Republican Party?”

Similarly, Smith writes: “Do serious interviews with Republican presidential candidates running against Trump. They know the numbers as well as you do. So why are they running?… Are they worried about where GOP is headed? Do they want real issues debated? Are they expecting a crack in Trump supporters? Why do they think it’s not as hopeless as the media says it is?”

Everything is Different Now

Dan Gillmor, who teaches journalism at Arizona State University, advises: “Recognize that this is an emergency, and adjust coverage accordingly. “Democracy, and by extension freedom of the press, are on the ballot next year, but journalism is still doing business as usual. It is long, long past due to take an activist stance on behalf of democracy. The people who want to end it — and who have made clear they will do so if put (back) into power — count on journalists’ adherence to norms that were appropriate in the late 20th century. ”

Pickard adds: “Journalists should keep a laser-like focus on how one party has, in so many ways, given up even pretending to care about the integrity of our fragile democracy and whether democratic governance is an ideal worth protecting. In particular, coverage of Trump should remind us all to what extent he attempted to subvert the 2020 election, and that he continues to do great damage to our political processes.”

“Recognize the malignant uniqueness of the current political moment,” writes Charles Pierce, politics columnist for Esquire. That includes acknowledging how we got here: “Recognize that this moment is the result of 40 years of conservative politics, and that DJT is a symptom, not a cause,” Pierce writes.

Rosen recommends: “The reporting and analysis of politics could become more explicitly (and creatively) pro-democracy, pro-voting, and pro-truth. These have always been background assumptions of strong public service journalism. Now they need to be brought into the foreground as major and timely commitments, as basic as ‘democracy dies in darkness.’ Then it’s up to journalists to work out the consequences of those commitments for their own practices.”

In particular, he suggests: “Newsrooms local, statewide, and national could develop through their own research a ranking of ‘live threats to democracy in our coverage area,’ which they then use to generate assignments, level with their audience, and sound the alarm when needed.”

Call Out Misinformation

It’s not enough to call out a lie. It’s a disservice to the public if you don’t explain its purpose. I wrote about that in my column “The ‘why’ behind the lie“.

Ben-Ghiat writes: “Speak to experts on disinformation/information warfare and authoritarianism to understand the media strategies of Trump, GOP and enablers. Do not just report the what always include in the headline the why: the infowar strategy behind their words.”

And don’t leave out what is arguably the greatest spreader of misinformation: “Call out Fox ‘News’ for what it is: a propaganda mill for the Republican Party,” advises Gillmor.

Defend Yourself

Journalism itself is under attack. That’s a big story.

“We don’t talk about the threats journalists face until there is a raid or a shooting,” Ben-Ghiat writes. “Helping the public understand how difficult it is for journalists to do their jobs due to the climate of hostility engendered by the enemies of the truth is important. In countries where democracy has fallen, such as the Philippines, journalists who fight for the truth or cover corruption are national heroes.”

“Don’t contribute to undermining your own legitimacy,” advises Mercieca.

Keep the Trials and the Campaign Separate

“The candidate is a defendant and the defendant is a candidate. Barring an act of god, or the sudden intervention of his coronary arteries, that is going to be the case throughout the 2024 cycle, and it is going to require a massive course correct in the election coverage,” Pierce writes.

“No story about the legal side should make heavy reference to the political consequences as regards the presidential race. Campaign polling should have no relevance to reports from the courtroom. If the indictments improve his standing in the election, that should be taken as evidence of a deeper failure of the entire system, not as a curious, quaint phenomenon described in anodyne terms.”

Follow the Money

Political journalists spend a lot of time reporting on how much money the candidates have raised. But they don’t look hard enough at where it comes from, and they don’t connect the candidates to the donors who fund them, even though that can be incredibly telling.

Investigative reporter and author David Cay Johnston writes: “Policy, the character of candidates, and their financial backers are all interrelated, and they need to be presented in ways that don’t bore readers, but are telling about who candidates really are, and what they are highly likely to do an office.”

Pickard calls for journalists to “Discuss the obscene amounts of money being spent on campaigns, especially on political advertising, where this money is coming from, and how much of an extreme outlier the U.S. political election process is compared to other democracies across the planet.”

Jeff Cohen, the founder of FAIR and a retired journalism professor, recommends: “Focus less on the amount of campaign funding to each candidate, and more on where funding is coming from, and what interests funders have in government policy.”

He adds: “Right-wing candidates like DeSantis regularly make populist-sounding appeals to the ‘working class’ (seemingly aimed at the ‘white working class’) and attack ‘corporate media,’ but they are funded heavily by powerful and exploitative corporate interests. Journalists need to expose the identities and policy interests of these big GOP funders.

“Similarly, Democrats like Biden regularly invoke ‘working families,’ but are heavily funded by executives (or lawyer/lobbyist/consultants) from big finance, big tech, big real estate, big healthcare, etc. — and journalists need to expose their identities and interests. ”

And journalists should acknowledge that money affects how they do their job as well.

Writes Pickard: “I think we should always be asking what the structural conditions are that encourage status quo media coverage, and we need to consider how we can change those conditions to encourage better journalism. Political journalism, especially during campaign seasons, is big money. And these financial incentives warp our news media.”

The Cartoons

Finally, Mike Luckovich, editorial cartoonist for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, has a suggestion clearly pointed at the Washington Post opinion section, whose downgrading of political cartoons you can read about here.

“As a cartoonist,” Luckovich writes, “I think in this moment, when our democracy is at stake, that newspapers should run hard-hitting cartoons that hit Trump, Republican and Fox News lies, rather than New Yorker type gag cartoons.” (Dan Froomkin, August 30, 2023, Press Watchers).

________________________________

A very interesting article on Republicans, the Constitution and Democracy.

Republicans Don’t Mind the Constitution. It’s Democracy They Don’t Like.

A very large portion of my party,” Senator Mitt Romney of Utah tells McKay Coppins of The Atlantic, “really doesn’t believe in the Constitution.”

Romney doesn’t elaborate further in the article, and Coppins, who spoke to him in depth and at length, beginning in 2021, for a forthcoming biography, does not speculate on what exactly Romney meant with this assessment of his co-partisans.

If Romney was using “the Constitution” as a rhetorical stand-in for “American democracy,” then he’s obviously right. Faced with a conflict between partisan loyalty and ideological ambition on one hand and basic principles of self-government and political equality on the other, much of the Republican Party has jettisoned any commitment to America’s democratic values in favor of narrow self-interest.

The most glaring instance of this, of course, is Donald Trump’s attempt to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election, which was backed by prominent figures in the Republican Party, humored by much of the Republican establishment and affirmed, in the wake of an insurrectionary attack on the Capitol by supporters of the former president, by a large number of House and Senate Republican lawmakers who voted to question the results.

Other examples of the Republican Party’s contempt for democratic principles include the efforts of Republican-led state legislatures to write political majorities out of legislative representation with extreme partisan gerrymanders; the efforts of those same legislatures to raise new barriers to voting in order to disadvantage their political opponents; and the embrace of exotic legal claims, like the “independent state legislature theory,” meant to justify outright power grabs.

In just the past few months, we’ve seen Tennessee Republicans expel rival lawmakers from the State Legislature for violating decorum by showing their support for an anti-gun protest on the chamber floor, Florida Republicans suspend a duly elected official from office because of a policy disagreement, Ohio Republicans try to limit the ability of Ohio voters to amend the State Constitution by majority vote, Wisconsin Republicans float the possibility that they might try to nullify the election of a State Supreme Court justice who disagrees with their agenda and Alabama Republicans fight for their wholly imaginary right to discriminate against Black voters in the state by denying them the opportunity to elect another representative to Congress.

It is very clear that given the power and the opportunity, a large portion of Republican lawmakers would turn the state against their political opponents: to disenfranchise them, to diminish their electoral influence, to limit or even neuter the ability of their representatives to exercise their political authority.

So again, to the extent that “the Constitution” stands in for “American democracy,” Romney is right to say that much of his party just doesn’t believe in it. But if Romney means the literal Constitution itself — the actual words on the page — then his assessment of his fellow Republicans isn’t as straightforward as it seems.

At times, Republicans seem fixated on the Constitution. When pushed to defend America’s democratic institutions, they respond that the Constitution established “a republic, not a democracy.” When pushed to defend the claim that state legislatures have plenary authority over the structure of federal congressional elections and the selection of presidential electors, Republicans jump to a literal reading of the relevant parts of Article I and Article II to try to disarm critics. When asked to consider gun regulation, Republicans home in on specific words in the Second Amendment — “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed” — to dismiss calls for reform.

Trump tried to subvert American democracy, yes, but his attempt rested on the mechanisms of the Electoral College, which is to say, relied on a fairly literal reading of the Constitution. Both he and his allies took seriously the fact that our Constitution doesn’t require anything like a majority of the people to choose a president. Attacks on representation and personal freedom — the hyper-gerrymandering of legislatures to preserve and perpetuate minority rule and the attempts to limit or restrict the bodily autonomy of women and other Americans — have operated within the lines drawn by the Constitution, unimpeded or even facilitated by its rules for structuring our political system.

Republicans, in other words, do seem to believe in the Constitution, but only insofar as it can be wielded as a weapon against American democracy — that is, the larger set of ideas, intuitions, expectations and values that shape and define political life in the United States as much as particular rules and institutions.

Because it splits sovereignty between national and subnational units, because it guarantees some political rights and not others, because it was designed in a moment of some reaction against burgeoning democratic forces, the Constitution is a surprisingly malleable document, when it comes to the shaping of American political life. At different points in time, political systems of various levels of participation and popular legitimacy (or lack thereof) have existed, comfortably, under its roof.

Part of the long fight to expand the scope of American democracy has been an ideological struggle to align the Constitution with values that the constitutional system doesn’t necessarily need to function. To give one example among many, when a Black American like George T. Downing insisted to President Andrew Johnson that “the fathers of the Revolution intended freedom for every American, that they should be protected in their rights as citizens, and be equal before the law,” he was engaged in this struggle.

Americans like to imagine that the story of the United States is the story of ever greater alignment between our Constitution and our democratic values — the “more perfect union” of the Constitution’s preamble. But the unfortunate truth, as we’re beginning to see with the authoritarian turn in the Republican Party, is that our constitutional system doesn’t necessarily need democracy, as we understand it, to actually work. (Jamelle Bouie, New York Times).

________________________________

Hag Sameach & Shana Tova.

A happy and healthy year to all the readers of the Roundup.

The 10 holy days of the Jewish New Year began last night. Sweet wishes to all, those who celebrate and those who do not.

I will take 2 days off, to honor my ancestors and the cycle of life - we start again, move into another revolve around the sun, and so it is.

See you on Tuesday. Thank you all for revolving with me.

Annette

________________________________