Saturday, March 29, 2025. Annette’s Roundup for Democracy.

Where universities find themselves under the Trump regime.

Over 50 universities face federal investigations as part of Trump's anti-DEI campaign - ABC News

WASHINGTON -- More than 50 universities are being investigated for alleged racial discrimination as part of President Donald Trump’s campaign to end diversity, equity and inclusion programs that his officials say exclude white and Asian American students.

The Education Department announced the new investigations Friday, one month after issuing a memo warning America’s schools and colleges that they could lose federal money over “race-based preferences” in admissions, scholarships or any aspect of student life.

“Students must be assessed according to merit and accomplishment, not prejudged by the color of their skin,” Education Secretary Linda McMahon said in a statement. “We will not yield on this commitment.”

The PhD Project.

Most of the new inquiries are focused on colleges’ partnerships with the PhD Project (https://phdproject.org), a nonprofit that helps students from underrepresented groups get degrees in business with the goal of diversifying the business world.

Department officials said that the group limits eligibility based on race and that colleges that partner with it are “engaging in race-exclusionary practices in their graduate programs.”

The group of 45 colleges facing scrutiny over ties to the PhD Project include major public universities such as Arizona State, Ohio State and Rutgers, along with prestigious private schools like Yale, Cornell, Duke and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

A message sent to the PhD Project was not immediately returned.

Six other colleges are being investigated for awarding “impermissible race-based scholarships,” the department said, and another is accused of running a program that segregates students on the basis of race.

Those seven are: Grand Valley State University, Ithaca College, the New England College of Optometry, the University of Alabama, the University of Minnesota, the University of South Florida and the University of Tulsa School of Medicine.

The department did not say which of the seven was being investigated for allegations of segregation.

The Feb. 14 memo from Trump's Republican administration was a sweeping expansion of a 2023 Supreme Court decision that barred colleges from using race as a factor in admissions.

That decision focused on admissions policies at Harvard and the University of North Carolina, but the Education Department said it will interpret the decision to forbid race-based policies in any aspect of education, both in K-12 schools and higher education.

In the memo, Craig Trainor, acting assistant secretary for civil rights, had said schools’ and colleges' diversity, equity and inclusion efforts have been “smuggling racial stereotypes and explicit race-consciousness into everyday training, programming and discipline."

The memo is being challenged in federal lawsuits from the nation’s two largest teachers’ unions. The suits say the memo is too vague and violates the free speech rights of educators. (ABC News - source AP Education reporting).

Trump Demands Major Changes in Columbia Discipline and Admissions Rules

A letter outlining “immediate next steps” arrived less than a week after the administration said it was canceling $400 million in grants and contracts.

Protesters occupied Hamilton Hall last spring. The Trump administration said Columbia had “fundamentally failed to protect American students and faculty from antisemitic violence and harassment.”

The Trump administration on Thursday demanded that Columbia University make dramatic changes in student discipline and admissions before it would discuss lifting the cancellation of $400 million in government grants and contracts.

It said the ultimatum was necessary because of what it described as Columbia’s failure to protect Jewish students from harassment.

The government called for the university to formalize its definition of antisemitism, to ban the wearing of masks “intended to conceal identity or intimidate” and to place the school’s Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies Department under “academic receivership.”

“We expect your immediate compliance,” officials from the General Services Administration, Department of Education and Department of Health and Human Services said in a letter.

The Trump administration’s move to cut Columbia’s grants and contracts represented an extraordinary escalation of the government’s actions against the university.

Columbia, it said, “has fundamentally failed to protect American students and faculty from antisemitic violence and harassment.”

A Columbia spokeswoman said Thursday evening that the school was “reviewing the letter" from the three government agencies, adding, “We are committed at all times to advancing our mission, supporting our students, and addressing all forms of discrimination and hatred on our campus.”

On social media, Jameel Jaffer, director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia, described the government’s letter as essentially saying, “We’ll destroy Columbia unless you destroy it first.”

Hours earlier, the school announced a range of disciplinary actions against students who occupied a campus building last spring, including expulsions and suspensions.

The punishments levied include “multiyear suspensions, temporary degree revocations and expulsions,” according to a statement. The school did not release the names of students who would be punished, in compliance with federal privacy laws, according to a university spokeswoman. It is unclear how many students have been punished.

The announcement came one day after Gregory J. Wawro, a professor of political science who also serves as the university’s rules administrator, said in a statement that the hearings for students accused of violations “in connection with the April 17-18 encampment on the South Lawn and the occupation of Hamilton Hall” had been completed.

Student defendants were allowed to bring two advisers, including legal counsel, to hearings, which were held over video conference, according to a Columbia employee with knowledge of the process who spoke on the condition of anonymity because she was not authorized to speak publicly.

Late Thursday, Columbia’s interim president, Katrina Armstrong, said that the Department of Homeland Security had searched two dorm rooms after presenting two federal search warrants. In an email to students and staff, and a news release, Ms. Armstrong said that no one was detained and nothing had been taken. She did not say what the target of the warrants was.

Columbia University and the D.H.S. did not immediately respond to requests for comments after working hours.

The Trump administration has placed increasing scrutiny on universities in recent weeks. On Monday, it warned 60 other universities they, too, could face penalties from pending investigations into antisemitism on college campuses.

Last spring, Columbia began to issue suspensions of pro-Palestinian demonstrators who had been encamped for more than a week on campus as they protested the university’s investment in Israel, including its dual-degree program with Tel Aviv University.

A protest that had mostly been nonviolent then took a turn, with demonstrators breaking into and seizing Hamilton Hall, an academic building. After about 20 hours, Columbia’s president at the time, Dr. Nemat Shafik, called in the city’s Police Department. Officers in riot gear arrested dozens of people.

A maintenance worker who was trapped in the building was physically injured in the melee.

In all, nearly 50 pro-Palestinian demonstrators who had been inside Hamilton Hall were arrested, along with more than 100 others who were protesting in and around the campus.

Questions about how the university administration was handling discipline have dogged the school since.

In February, the House Committee on Education and Workforce sent a letter to Ms. Armstrong, and Columbia’s board chairs, David Greenwald and Claire Shipman, listing “numerous antisemitic incidents” that it said had taken place in the last two academic years.

Those incidents include the student occupation of Hamilton Hall last April, the protest against a class taught by former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and the disruption of an Israeli history class.

Representative Tim Walberg, a Republican from Michigan who is the chair of the House committee, said he was glad that there has been forward movement but expressed frustration that the school has not provided the detailed disciplinary records his committee seeks.

“I welcome the news that some lawbreaking individuals are being held accountable,” Mr. Walberg said, “but I remain skeptical about Columbia University’s long-term ability to continue to hold pro-terror supporters accountable given the school’s obfuscation.”

The university said that it began its judicial process last summer, filing its complaints against students with the University Judicial Board, which is an independent panel of faculty, students and staff.

Students notified on Thursday of the sanctions have five business days to file an appeal, on grounds that there was a procedural error, availability of new information or “excessiveness of sanction.” A university appellate board has 10 days to issue a ruling.

Columbia University Apartheid Divest, a group that helped organize the protests and last fall asserted its support for “armed resistance,” said on its Instagram page Thursday that “the university’s extreme repression is a panicked attempt at silencing the movement for Palestinian liberation,” adding that “they have seen our unyielding commitment to Palestine firsthand over the last year, and they are terrified.”

The announcement of sanctions can be seen as a sign that “Columbia has turned the corner,” said Professor Joshua Mitts, a professor in the law school who this semester is teaching a seminar on free speech and civil liberties on campus. He is also the adviser to Law Students Against Antisemitism, a campus group.

Calling the judicial process “fair and transparent,” Mr. Mitts said that the university showed its fidelity to due process, free speech and academic freedom as it sought to upend antisemitism.

“This is Columbia at its best,” he said. (New York Times).

Read the letter to Columbia here

‘Nobody can protect you.’ Columbia dean warns foreign students after Mahmoud Khalil arrest

Experts had mixed feelings about Jelani Cobb cautioning foriegn students not to publish articles about Gaza or Ukraine.

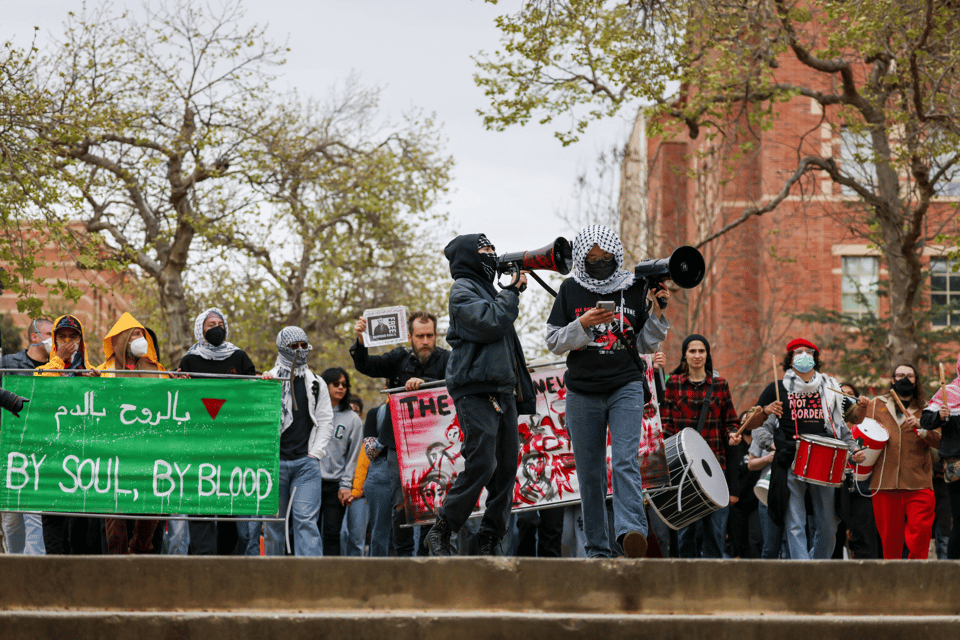

Pro-Palestinian protesters march at UCLA on Tuesday, opposing ICE’s detainment of Mahmoud Khalil, a Palestinian activist who led protests at Columbia University last year.

Amid the fallout at Columbia University over the Department of Homeland Security’s arrest of recent graduate Mahmoud Khalil, one comment stood out: “Nobody can protect you.”

The remark came from Jelani Cobb, dean of Columbia’s prestigious journalism school, and was directed to a group of international students on visas who are nearing graduation.

Cobb and Stuart Karle, a First Amendment lawyer and adjunct professor at Columbia, cautioned the graduate students against posting commentary about the Middle East on social media or reporting on Gaza, Ukraine or the protests against Khalil’s arrest, the first in what President Donald Trump has pledged will be many more detentions and possible deportations of non-citizens who participated in campus demonstrations against Israel.

“These are dangerous times,” Cobb added, in remarks reported Wednesday by The New York Times.

For some, the comment embodied a dangerous tone of accommodation to authoritarian overreach by the Trump administration. “Columbia j-school students from abroad are being told to obey in advance,” Dan Froomkin, who runs the media monitor Press Watch, wrote on Bluesky.

Columbia’s administration, which has been under heavy fire from Congressional Republicans and the Trump administration, has been criticized by activists for failing to defend Khalil and other student protesters. Federal agencies announced last week that they were canceling $400 million in grants to the university and President Donald Trump’s antisemitism task force plans to visit the school as part of a national tour. Katrina Armstrong, who Khalil emailed for assistance with online and legal threats the day before he was detained, has been criticized for not releasing a statement directly commenting on his arrest, which took place at university housing.

Others said that Cobb was only sharing a depressing but real truth with students who are months away from receiving a diploma.

“If you are not a U.S. citizen, if you publish anything that could be interpreted as pro-Palestinian, I think that it’s likely that you will lose your visa or your green card,” said Kelly McBride, an ethics expert at Poynter, the nonprofit journalism institute.

She added that the inability to assign visa or green-card holders, including Palestinians, to cover the response to the Israel-Hamas war would be a loss for readers. “We lose insights that American citizens might not be able to articulate,” McBride said.

Karle, a veteran media lawyer, said that his advice to the Columbia students was the same that he would provide to any clients: “When in Rome, do as the Romanians do,” meaning it is important to recognize that a country’s laws apply differently to citizens and non-citizens. (The Forward).

One more thing.

U.S. Arrests 2nd Person Tied to Pro-Palestinian Protests at Columbia.

The action came less than a week after Mahmoud Khalil, a recent Columbia graduate and a prominent figure in campus demonstrations, was arrested.

A second person who took part in pro-Palestinian protests at Columbia University has been arrested by U.S. immigration agents, after overstaying a student visa, federal officials said on Friday, the latest turn in the crisis engulfing the Ivy League institution.

The person, identified by the authorities as Leqaa Kordia, is Palestinian and from the West Bank. She was arrested in Newark on Thursday, officials said. Her student visa was terminated in January 2022, and she was arrested by the New York City police last April for her role in a campus demonstration, the Homeland Security Department said in a statement.

The agency also released a video on Friday that it said showed a Columbia student, identified as Ranjani Srinivasan, preparing to enter Canada after her student visa was revoked.

The announcements, by Kristi Noem, the homeland security secretary, reflected an escalation of the Trump administration’s focus on Columbia, where protests over the war in Gaza last year ignited a national debate over free speech and antisemitism, and prompted similar demonstrations at dozens of other campuses. (New York Times).

On Schumer’s decision to vote yes.

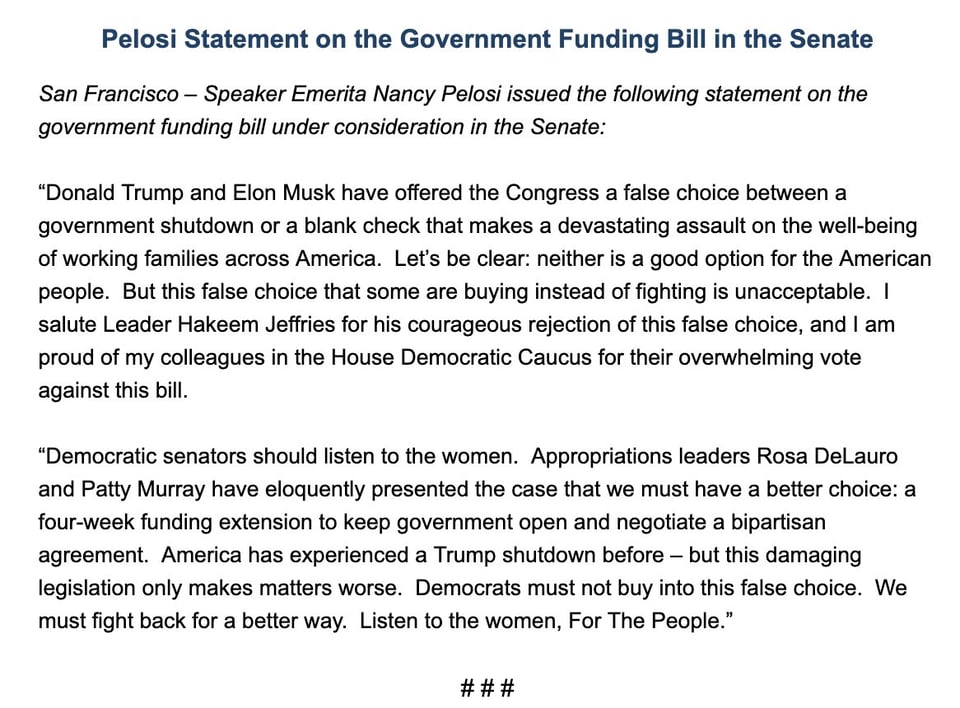

Pelosi reacts to Schumer’s decision

Representative Nancy Pelosi of California, the former speaker, released a scalding statement on Senator Chuck Schumer’s decision to clear the way for a vote on the Republican spending bill. “Donald Trump and Elon Musk have offered the Congress a false choice between a government shutdown or a blank check that makes a devastating assault on the well-being of working families across America. Let’s be clear: Neither is a good option for the American people. But this false choice that some are buying instead of fighting is unacceptable.”

Ten Senate Democrats cave to avert government shutdown.

Ten Senate Democrats joined with the Republican majority in voting to move forward with a stopgap spending bill Friday — clearing the path to avoid a government shutdown.

Why it matters: Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) is facing outrage from his party, including House leadership, over his decision to vote for the bill. Many Democrats wanted to force a shutdown to protest President Trump and Elon Musk's sweeping federal spending cuts.

The key procedural vote was 62-38. Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) was the only Republican who voted "no."

The Senate voted 54-46 a short time later to send the stopgap measure to Trump for his signature ahead of a midnight deadline. It funds the government through Sept. 30.

Schumer did manage to get GOP leadership to agree to hold a vote to ensure that the D.C.'s budget did not suffer a $1 billion cut. The House's bill was written to include the budget reduction, sparking concern.

Zoom in: After days of lengthy caucus meetings and threats of a shutdown, Schumer announced Thursday evening he would be voting "yes" to clear the way for Republicans to pass the spending bill.

Despite public outrage especially from House progressives, Schumer delivered the needed votes, drawing support from moderates, members of his leadership team and retiring Democrats.

Democratic Sens. Richard Durbin (Ill.), Catherine Cortez Masto (Nev.), John Fetterman (D-Pa.), Kirsten Gillibrand (N.Y.), Maggie Hassan (N.H.), Gary Peters (Mich.), Jeanne Shaheen (N.H.) and Brian Schatz (Hawaii) (Nev.) all voted "yes" in addition to Schumer, — as did Maine's Angus King, an Independent who caucuses with Democrats.

Cortez Masto told reporters before the vote that a shutdown would give Trump and Musk "more authority to cherry-pick" which agencies to close and "would cost the economy billions of dollars.

"I'm not going to exacerbate that," she added.

What to watch: The Senate voted to pass the measure Friday after leaders reached an agreement to speed up the process.

"Congratulations to Chuck Schumer for doing the right thing — Took 'guts' and courage!" Trump posted Friday on Truth Social, calling Schumer's decision to back the bill a "really good and smart move."

Zoom out: The bill largely maintains 2024 levels of spending through the end of September, with some additional defense funds and nearly $500 million for Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

The measure narrowly passed the House earlier this week with all Republicans except Rep. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.) voting for it and all Democrats except Rep. Jared Golden (D-Maine) voting against it.

Speaker Mike Johnson's (R-La.) ability to get the bill through the House — despite his narrow margins and skeptical conservatives — presented Senate Democrats with a tough choice: Join Republicans or risk getting blamed for a government shutdown. (Axios)

There is talk that, should AOC decide to primary Schumer, Governor Pritzker might be a strong source of funds for her campaign.

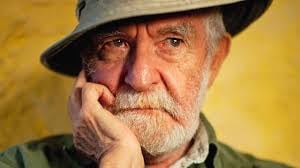

NPR’s Terry Gross honors Athol Fugard.

I do too, every day.

Remembering South African playwright Athol Fugard : NPR

Fugard, who died March 8, was a white South African whose plays explored the consequences of Apartheid. He was later awarded a Tony Award for lifetime achievement. Originally broadcast in 1986.

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. As a playwright, actor and director, Athol Fugard defied South Africa's apartheid system, and the government punished him for it. He died Saturday at the age of 92. We're going to listen back to the interview we recorded in 1986, eight years before the end of apartheid.

Fugard was a white South African who wrote about the emotional and psychological consequences of his country's white supremacist system. When Fugard co-starred in his 1961 play "The Blood Knot" with Black actor Zakes Mokae, they became the first Black and white actors in South African history to share a stage. Soon after, Fugard was approached by a group of Black actors seeking his help to start a company. Together, they formed the Serpent Players. The company was frequently harassed by the authorities. A few members were imprisoned. Fugard's reputation for defiance spread. And in 1967, the government revoked his passport. It was restored four years later.

Fugard wrote more than 30 plays, including "'Master Harold'...And The Boys" and "Boesman And Lena." He co-wrote the plays "Sizwe Banzi Is Dead" and "The Island" with the Black South African actors John Kani and Winston Ntshona. His plays have been staged in the U.S. Six of his plays were produced on Broadway. He won a Tony Award for lifetime achievement in 2011.

When I spoke with Fugard in 1986, I asked him why he remained in South Africa, where he lived under the apartheid system he opposed.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

ATHOL FUGARD: I suppose it's a question of my continued existence as a writer. I just couldn't see myself writing about any other place or any other time. I have, on occasions in the past, described myself as a regional writer, not meaning to be falsely modest or anything like that, but a regional writer, in the sense, I think, that Faulkner was a regional writer in America. And my region is South Africa.

GROSS: Do you feel constrained there at all by limitations of what will be allowed to be performed on stage?

FUGARD: I think I've got - I think I've become so used to living with that danger, with the danger of censorship. And in some ways, the situation today is a lot easier than it was in the past. I mean, I had to contend with a South Africa that was much more authoritarian in terms of its control over the arts than is the case today, where the government has attempted to persuade the outside world that it's moving in a liberal direction by allowing certain things to take place in theater and in the arts generally, which wasn't the case many years ago. I do not feel constrained. I've learned how to live with that.

GROSS: Do you ever feel that if your work is not censored, then you're not doing your job?

FUGARD: (Laughter) Yes. There is a terrible - there is the danger of a terrible sort of snobbery along those lines - you know? - that if you haven't been banned or if your work hasn't been censored or - let's put it even crudely - if you haven't been to jail at least once or if you haven't been raided by the security police and searched in the early hours of the morning, you haven't actually earned your credentials. Unfortunately, yes, I think a little bit of that does operate back home.

GROSS: What do you think is the power of theater or art in general to help topple the apartheid system? Do you think of art in those terms? Do you think of art as having an overt political function?

FUGARD: Well, it obviously does have that. I mean, I - for example, I heard a story about a South African who had had very, very strong, traditional South African attitudes and who, for some reason or the other, had been at Yale when I was doing "'Master Harold,'" who had come along and seen the play and who had been so affected by that production, who had in fact undergone a change of heart and - now, I have heard of quite a few cases like that in terms of responses to mine and other works of art, other - to novels and things like that from South Africa. So one has got to reckon with the fact that apparently art can do - be as profoundly effective as that in terms of people.

GROSS: You've had collaborative relationships with many Black actors, and I'm sure that there are many obstacles in having that kind of relationship in a separatist country. Perhaps one of the first relationships you had like that was with Zakes Mokae in "The Blood Knot." Were there any obstacles in actually getting together and working together on the play and then afterwards on performing it?

FUGARD: Oh, yes. Well, firstly, I mean, just in - just for Zakes and myself to get together as two actors and to go up onto a stage, that had never happened before in South Africa - that a Black man and a white man had appeared on a stage, and a Black actor or a white actor had appeared on a stage at the same time. We were the first in that regard, and all sorts of complications were attendant on that. I mean, in traveling around the country when we eventually took "Blood Knot" to different cities, Zakes had to travel third class because he had no other choice. I traveled first class. Life was very complicated.

Zakes, on a point of principle, refused to carry his reference book. He made a - wanted to make a political statement in his personal life. I knew that if we didn't have that book around with us, that we'd be in trouble. Zakes would be in jail, and the show couldn't go on. So I carried the book for Zakes, and whenever the police stopped us, I presented it and pretend that Zakes was my - was working for me, things like that. Yes, there've been lots of complications along those lines.

GROSS: Did that affect the relationship that you had with each other since when officials asked, you had to be in the superior-employer relationship?

FUGARD: (Laughter) No, you're quite right. Well, no, you've learned - you learn to play those games as part of your survival mechanism in South Africa. I mean, you know, many, many times, in order to bail Zakes and myself out of a tight spot, for example, with the police, I would put on a heavy Afrikaner act and talk to the policeman and - as if I was a good Afrikaner and Zakes was my boy, my employee. And Zakes knew that I was doing it in order to - you know, to keep the two of us out of jail.

GROSS: You also, in the 1960s, were a co-founder of a group called the Serpent Theater, which was also integrated. What were some of the difficulties then of rehearsing together? Were you allowed into the Black townships? Were they allowed into the white communities?

FUGARD: Well, the Serpent Players were a group I worked with in my hometown of Port Elizabeth. And Port Elizabeth has always been a difficult area for me because the authorities there have consistently refused to allow me to go into the Black ghetto areas to - into the Black townships. So in order to work with Serpent Players, we had to find a sort of neutral territory halfway between their Black world and my white world and, in fact, in one of the twilight zones in Port Elizabeth. And that is where we would get together and rehearse and meet. And I was faced with these sort of - a rather unhappy situation, where sometimes I would direct a play and not be able to attend performances of it.

GROSS: Your play "'Master Harold'...And The Boys" is based in part on the relationship you had when you were young with a Black man who was a waiter, I think, at a cafe that your mother ran. There's an incident in the play that I think is based on an incident in your life, where the young white boy, who's the son of the mother who owns the cafe, who's really, very close with the waiter, spits in his face. From what I understand, it was very difficult for you to write that part in. Can I ask about the personal significance that that event had for you?

FUGARD: Yes, that did happen. Tragically, regrettably, a moment of - a cauterizing, traumatic moment of shame in my life - that I still live with - that was there at a point in my childhood coming out of - I can remember the day, a spasm of bewilderment and confusion. I can't remember what had upset me so much that day, but I turned on the one person I had in my life, the one true friend I had. And he was a Black man, and he worked for my family. He worked for my mother as a waiter in this little tearoom we had.

I spat in Sam's face. And the moment I had done it, I knew what I had done. A second after I had done it, I knew that I had most probably done one of the truly ugly things of my entire life, even though I was only 13 years old. I knew that it was going to be very, very hard for me to ever equal the ugliness of what I had done because, I mean, I had sullied, I had dirtied what was one of the most beautiful things I had in my life was that friendship. And I've lived with that - I lived with that shame and still do live with the shame of that act.

And when it came to writing the play, I didn't write the play just for that reason in an attempt to finally deal with that moment. I'd been trying to write about Sam and another man that worked for the family as well, also as a waiter, a man called Willie. I had been trying to write about Sam and Willie for a long time in my life, just to celebrate them because they were two very, very beautiful human beings. And very instrumental, very important in me, finally starting on a process of emancipation from the prejudices of my country, of the traditional South African way of life.

And I just wanted to celebrate those two men. And when I finally put the little boy in there with them, I realized that I potentially had an opportunity to do both that and also deal with this unbelievably ugly thing that I had done. And in writing the play, I thought for a long time that my craft as a playwright would stand me in good stead and that I would not necessarily have to sink so low as to actually have up there onstage a moment when the white boy spat in the Black man's face. But the deeper I worked myself into the play, and the more I developed the play and wrote it, the more I realized that there was just no avoiding that moment.

GROSS: Is there a moment when you can point to and say, this is when I realized that the system of apartheid was evil, was unjust?

FUGARD: Yes. I mean, I knew it was. The process of discovering that it was evil and unjust, that it maimed and mutilated people, destroyed them, was something that happened, you know, more or less from the time I spat in Sam's face. That was but the full extent, the sort of - the moment of certainty, the moment when I realized the extent of what that system was doing came when I, for a variety of reasons, took on a job in Johannesburg, which was to be the clerk of a court, of a criminal court that sent - that tried Black people for offenses in terms of the passbook that they are compelled by law to carry.

And it's when I sat in that courtroom five days a week for a period of about six months and watched a Black man or woman and sometimes a child being disposed of at the rate of one every three minutes, being sent off to jail. When I saw that tidal wave of humanity being processed by this diabolical machine that the full extent of the - of what apartheid meant and does and was doing dawned on me - when it was brought home to me. Now, that was one of the - if I can talk about spitting in Sam's face as being the traumatic personal moment, that was the traumatic social moment. That was the moment in terms of my political conscience.

GROSS: Was that about the time that you started writing plays also?

FUGARD: Yes. Yes. That is, in fact, the period when the very - my very first published play was written. I still think of it as an apprenticeship work, and it precedes the "Blood Knot," a play called "No-Good Friday." It was also the first play that - it marks the first meeting with Zakes Mokae, who's in the "Blood Knot" with me.

GROSS: We're listening back to the interview I recorded in 1986 with playwright, actor and director Athol Fugard. He died Saturday at age 92. We'll hear more of the interview after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF GILAD HEKSELMAN'S "DO RE MI FA SOL")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. Let's get back to the interview I recorded with white South African playwright, actor and director Athol Fugard. He died Saturday at age 92. His plays were in opposition to his country's apartheid system. One of the consequences he faced was being unable to leave South Africa for four years because the government revoked his passport. I spoke with him in 1986, eight years before the end of apartheid.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

GROSS: I know one thing that drives a lot of white people who live in South Africa crazy is that every time you sit on a bench or board a bus or enter into certain stores, you are in a way making a complicit act with apartheid if that is a segregated bench or bus or store. And I wonder how you reconcile that now.

FUGARD: The thing that you have to live with constantly in South Africa as a white South African who opposes the system is that even in opposing the system, even in doing what you can by way of writing plays or protesting or doing this, your daily life is still rotten with compromise. And you're involved in that very, very dangerous exercise of hoping that what you do at one level outweighs that, the way you live, the fact that you live in a whites-only area among affluent white people. You hope that those compromises haven't irremediably stained or poisoned your life, that you somehow are still making some contribution towards an eventual decency in that society. It's a dangerous lifestyle. I mean, but there's no way of avoiding it other than to get out. And if I get out, how am I contributing to anything then? I still have got to believe that being inside that country, inside that society, even though I have to live with these compromises, that somehow I still contribute more by being inside and doing my thing than I would be by going into voluntary or enforced exile.

GROSS: Do you feel that yourself and other white people who oppose apartheid end up feeling that they have to shoulder a lot of guilt for being there or for acts that may seem compromised from your youth, before you gained the awareness that you have now?

FUGARD: Oh, that's very important. You really are touching on one of the major factors in the psychology of the white South African, is the operation, the presence of, the genesis of, the hoped for elimination of guilt. Major, major factor. God knows I think that - I mean, I lived with that as one of the most potent factors in my psychology. I'm, as I've said before, 53 years old now. I must admit that as I'm getting older now, I'm getting a bit tired of being guilty, of feeling guilty. And I'm beginning to ask myself, just how guilty am I? Haven't I, in fact, laid a lot of those guilts on myself? Am I as guilty as I thought I was? And, well, let me just leave it at that. I mean, just say that I'm in the process of really addressing the question of my guilt, and that I think that possibly a lot of my writing - some of my writing in the future might be an examination of that fact.

GROSS: Do you have to ask yourself how productive guilt is at a certain point?

FUGARD: True guilt, the admission of true guilt, is very important and can only be productive. To act out of false guilt is stupid and pointless.

GROSS: Your plays have been performed in South Africa and in America. I was thinking that American audiences might find it easier to give themselves over to your plays in that the kind of racism that is addressed in your plays is the kind of racism that exists in South Africa. And what I'm saying here is that I think American racism is a more covert kind of racism than the apartheid kind. And because it's happening over there, and we are not directly implicated in it, it's easier to perhaps not internalize some of the statements that you're making within your plays.

FUGARD: Yeah, very interesting. You are absolutely right. I mean, I would go along with what you have just said 100%. It's very interesting actually to sort of examine in what respects racism in the two countries, racism in South Africa and America, are similar and dissimilar. The way racism in South Africa, because it is institutionalized, because it is, in a sense, the system - it is built into the system. The way in a sense it frees the individual of having to - you know what I mean? South Africa has never produced a lynch party. You get my point? The lynch mob is something unknown in South Africa for the simple reason our system does it for us. Our system hangs them. We don't have to get together as a mob and go out after the Black man.

GROSS: Is there a time that you have in your mind when you think you would actually leave South Africa, if things reached a certain point?

FUGARD: I would never leave South Africa. I'd like to believe I would never leave South Africa. But in making that decision, I mean, I sort of commit my wife to it as well. I haven't quite resolved that for myself yet.

GROSS: My interview with Athol Fugard was recorded in 1986. He died Saturday at age 92. After we take a short break, we'll listen back to an interview with soul singer Jerry Butler, who died last month. And we'll remember jazz drummer Roy Haynes. Today is the centennial of his birth. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF DOLLAR BRAND'S "ANTHEM FOR THE NEW NATION")

Enjoy the weekend, as you can, with our bright days with more sunlight. In NYC, we are seeing other real signs of spring too.

I will see you on Tuesday, unless there is something critical that grabs my attention.

Somehow we will get through this.