Saturday, July 1, 2023. Annette’s News Roundup.

I think the Roundup makes people feel not so alone.

To read an article excerpted in this Roundup, click on its blue title. Each “blue” article is hyperlinked so you can read the whole article.

Please feel free to share.

Invite at least one other person to subscribe today! buttondown.email/AnnettesNewsRoundup

_________________________

Joe is always busy.

Whoa. President Biden released a statement about the student loan ruling & doesn't hold back: "Republicans had no problem w pandemic-related loans for their own businesses. But providing relief to millions of hard-working Americans, they did everything in their power to stop it."

— Victor Shi (@Victorshi2020) June 30, 2023

Joe promised loan relief. He will deliver.

Here’s what to know about the student loan forgiveness decision.

The Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority struck down President Biden’s proposal to cancel at least some student debt for tens of millions of borrowers, saying it overstepped the powers of the Education Department.

In a 6-to-3 decision, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote that a mass debt cancellation program of such significance required clear approval by Congress.

Chief Justice Roberts declared that the administration’s logic — that the secretary of education’s power to “waive or modify” loan terms allowed for debt cancellation — was a vast overreach. “In the same sense that the French Revolution ‘modified’ the status of the French nobility,” he wrote, quoting a previous court decision.

Citing the same authority the Trump administration used to begin the pause on student loan payments during the pandemic, Mr. Biden promised in August to forgive $10,000 in debt for individuals earning less than $125,000 per year, or $250,000 per household, and $20,000 for those who received Pell grants for low-income families.

Nearly 26 million borrowers have applied to have some of their student loan debt erased, with 16 million applications approved. But no debts have been forgiven or additional applications accepted in light of the legal challenges.

The decision — a day after the court struck a blow against affirmative action policies in college admissions — effectively ended what would have been one of the most expensive executive actions in U.S. history.

In remarks after the ruling, Mr. Biden said his administration would try to enact a different student debt relief program under a 1965 law, the Higher Education Act. He predicted it would take longer than his original plan, but he called it “legally sound” and said his team had already started the process.

Mr. Biden also argued that he had already helped people with lots of student debt, but the decision increased the pressure on him to make good on a promise to a key constituency as the 2024 presidential campaign gets underway. He criticized Republicans in Congress — which does have the power to eliminate the debt — and highlighted what he called “the hypocrisy” of those who had pandemic-related aid forgiven or wanted to make former President Donald J. Trump’s tax cuts permanent.

Chief Justice Roberts wrote the 26-page majority opinion, with Justice Amy Coney Barrett adding a concurrence. Justice Elena Kagan wrote the dissent, saying the court was exceeding “its proper, limited role in our nation’s jurisprudence.” Read the full opinions here, or highlights here.

Although the administration’s plan was rejected by the court, there are still ways for borrowers to have student debt forgiven. Here are six ways to do it.

The amount of student debt held in America has skyrocketed over the last half-century, growing substantially faster than the increase in most other household expenses. More than 45 million people collectively owe $1.6 trillion — a sum roughly equal to the size of the economy of Brazil or Australia. (New York Times)

Biden promises to try again using the Higher Education Act. What is it?

Even as he denounced the Supreme Court ruling striking down his student debt forgiveness program and blamed Republicans for going after it, President Biden said Friday that his administration would start a new effort to cancel college loans under a different law.

The law Mr. Biden cited, the Higher Education Act of 1965, contains a provision — Section 1082 of Title 20 of the United States Code — that gives the secretary of education the authority to “compromise, waive, or release any right, title, claim, lien, or demand, however acquired, including any equity or any right of redemption.”

Some proponents of student debt relief had proposed that the Biden administration invoke this law as the basis of the president’s original loan cancellation program. In February 2021, for example, a group of Democrats including Senators Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Chuck Schumer of New York, the majority leader, introduced a resolution urging that step.

But as the Covid-19 pandemic swelled, the Biden administration instead used a law giving the secretary of education power to “waive or modify” federal student loan provisions in a national emergency. (A law passed by Congress to address the pandemic, the HEROES Act, may have made that route more attractive to policymakers, because it also exempted some agency actions from the usual rule-making and notice-and-comment processes.)

On Friday, in a lawsuit brought by Republican-controlled states, the six Republican-appointed justices ruled that the administration had stretched that law too far.

Should Mr. Biden’s new plan face a similar lawsuit, as seems likely as a matter of political reality, it would ultimately come before the same Supreme Court — raising the question of whether the wording differences between the statutes will make any difference.

In the majority ruling, Chief Justice Roberts said the words “waive or modify” could not be legitimately interpreted as conferring the power to cancel debt at a massive scale, and he invoked a conservative doctrinethat courts should strike down agency actions that raise “major questions” if Congress did not clearly and unambiguously grant such authority.

While Mr. Biden said he thought the Supreme Court on Friday had gotten the law wrong, he maintained that the new approach was “legally sound” and said that he had directed his team to move as quickly as possible. Miguel Cardona, the education secretary, had taken the first step to start the process, the president said.

Mr. Biden predicted that using the Higher Education Act would take longer than his original plan, but said, “In my view, it’s the best path that remains to providing as many borrowers as possible with debt relief.”

Ms. Warren in early 2021 also released a seven-page paper from September 2020 by Harvard Law School’s Legal Services Center, which she had commissioned, laying out an argument in greater detail for how the Higher Education Act could be used to cancel student debt. (New York Times)

REPORTER: did you overstep your authority (when you forgave student debt)?

— Mueller, She Wrote (@MuellerSheWrote) June 30, 2023

BIDEN: No. I think the SCOTUS misinterpreted the constitution

_________________________

Kamala is always busy.

My statement on the Supreme Court's ruling in 303 Creative v. Elenis: pic.twitter.com/Nm1BIXROzi

— Vice President Kamala Harris (@VP) June 30, 2023

My statement on the Supreme Court’s ruling in Nebraska v. Biden pic.twitter.com/XijsmOb2ZB

— Vice President Kamala Harris (@VP) July 1, 2023

_________________________

More from the Court.

Verdicts keep on coming.

Supreme Court Sides With Postal Carrier Who Refused to Work on Sabbath.

The Supreme Court broadened protections on Thursday for religious workers in a case that involved a mail carrier for the U.S. Postal Service who refused to work on his Sabbath.

In a unanimous decision, the justices rejected a test that had long been used to determine what accommodations an employer must make for religious workers, but declined to rule on the merits of the case, sending it back to a lower court to consider under a new standard.

Writing for the court, Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. said that the case gave it the “first opportunity in nearly 50 years” to explain the nuances of how workplaces must adapt to religious requests by employees.

For an employer to deny an employee’s request or a religious accommodation, Justice Alito wrote, it “must show that the burden of granting an accommodation would result in substantial increased costs in relation to the conduct of its particular business.” (The New York Times)

From the Forward. The Supreme Court unanimously expanded protections for religious workers, siding with a Christian postal worker who refused to work on Sundays. The justices ruled that most requests for religious accommodations should be granted, even if it comes at some cost to the employer — a change from a 1977 decision that religious groups said had too many loopholes to be meaningful. Jewish groups that often argue for church-state separation had lined up on the side of the mail carrier in this case, and Orthodox advocates said the ruling will help Jews seeking flexibility for daily prayer, kashruth and holidays.

Supreme Court sides with designer who declines to make same-sex wedding websites in LGBTQ rights case.

Washington — The Supreme Court on Friday ruled in favor of a Christian graphic artist from Colorado who does not want to design wedding websites for same-sex couples, finding the First Amendment prohibits the state from forcing the designer to express messages that are contrary to her closely held religious beliefs.

The court ruled 6-3 in favor of the designer, Lorie Smith. All six conservative justices sided with the designer, while the court's three liberals dissented. Justice Neil Gorsuch delivered the majority opinion.

"The First Amendment envisions the United States as a rich and complex place where all persons are free to think and speak as they wish, not as the government demands," Gorsuch wrote.

"If she wishes to speak, she must either speak as the State demands or face sanctions for expressing her own beliefs, sanctions that may include compulsory participation in 'remedial . . . training,' filing periodic compliance reports as officials deem necessary, and paying monetary fines," he said. "Under our precedents, that 'is enough,' more than enough, to represent an impermissible abridgment of the First Amendment's right to speak freely."

Justice Sonia Sotomayor read her dissenting opinion, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, from the bench — the second time she has done so this term.

The decision from the justices is the latest in a string of successes for religious organizations and individuals who have sought relief from the high court and its conservative majority. It also resolves a lingering question, left unanswered since 2018, of whether states can compel artists to express messages that go against their religious beliefs in applying their public-accommodation laws.

The Supreme Court has now said states cannot, as forcing artists to create speech would violate their free speech rights.

Smith's religious objection to same-sex weddings

The case was brought by Smith, who said her Christian beliefs prevent her from creating custom websites for same-sex weddings. Smith started her web design business, 303 Creative, roughly a decade ago, and wants to expand to create websites for weddings. In addition to wanting to design websites to express God's "design for marriage as a long-long union between one man and one woman," Smith also wants to post a message explaining why she cannot make custom websites for same-sex weddings, which states that doing so compromises her Christian beliefs and tells "a story about marriage that contradicts God's true story of marriage."

But refusing to design custom websites for a same-sex wedding, and detailing why she plans to do so, could violate Colorado's public-accommodation law.

The state's law prohibits businesses open to the public from refusing service because of sexual orientation and announcing their intent to do so. Smith has not yet created any wedding websites or been asked to do so for a same-sex wedding, but argues Colorado's law violates her free speech rights since the state is forcing her to express a message she disagrees with.

Smith filed a lawsuit against the state, but lost in the lower courts. A federal appeals court said that while her wedding websites are "pure speech," the state had a compelling interest in ensuring access to her services.

Smith appealed to the Supreme Court, and the justices considered during oral arguments in December whether states like Colorado can, in applying their anti-discrimination laws, compel an artist to express a message they disagree with.

The latest Supreme Court dispute over LGBTQ rights

The dispute was one of several to land before the justices in the wake of its 2015 landmark decision establishing the right to same-sex marriage that raised the question of whether a business owner can refuse service to LGBTQ customers because of their religious beliefs.

In 2018, the high court sided with a Colorado baker who was sued after he refused to bake a cake for a same-sex wedding, but did not address whether a business can deny services to LGBTQ peple. Instead, the Supreme Court said the state's Civil Rights Commission was hostile to baker Jack Phillips' religious beliefs in violation of the First Amendment.

In the years after, the Supreme Court declined to clarify whether states could force religious business owners to create messages that violate their conscience. But the court's rightward shift, solidified by former President Donald Trump's appointment of three justices, raised concerns that the Supreme Court would erode LGBTQ rights by allowing businesses to deny services to LGBTQ customers. (CBS News)

Justice Sotomayor’s dissent. Justice Sonia Sotomayor blasted the Supreme Court’s 6-3 decision to back a Christian wedding website designer’s choice not to provide services to gay couples, calling the decision “profoundly wrong” in a scathing dissenting argument read from the bench.

“Today, the Court, for the first time in its history, grants a business open to the public a constitutional right to refuse to serve members of a protected class,” Sotomayor wrote.

The associate justice harkened back to the civil rights and women’s rights movements in her dissent, suggesting that in recent years, gender and sexual orientation minority groups have faced “backlash to the movement for liberty and equality.”

“New forms of inclusion have been met with reactionary exclusion. This is heartbreaking. Sadly, it is also familiar,” she wrote. “When the civil rights and women’s rights movements sought equality in public life, some public establishments refused. Some even claimed, based on sincere religious beliefs, constitutional rights to discriminate. The brave Justices who once sat on this Court decisively rejected those claims.”

Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson joined Sotomayor’s dissenting argument. (The Hill).

Here are Sotomayor’s words. "What a difference five years makes." on Carson v. Makin.

Around the country, there has been a backlash to the movement for liberty and equality for gender and sexual minorities. New forms of inclusion have been met with reactionary exclusion. This is heartbreaking. Sadly, it is also familiar. When the civil rights and women's rights movements sought equality in public life, some public establishments refused. Some even claimed, based on sincere religious beliefs, constitutional rights to discriminate. The brave Justices who once sat on this Court decisively rejected those claims. Now the Court faces a similar test. A business open to the public seeks to deny gay and lesbian customers the full and equal enjoyment of its services based on the owner's religious belief that same-sex marriages are "false." The business argues, and a majority of the Court agrees, that because the business offers services that are customized and expressive, the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment shields the business from a generally applicable law that prohibits discrimination in the sale of publicly available goods and services. That is wrong. Profoundly wrong.”

Here is Justice Sotomayor’s full dissent.

Here is Justice Sotomayor’s full dissent.

Discrimination is wrong.

— Pete Buttigieg (@PeteButtigieg) June 30, 2023

Using religion as an excuse to discriminate is wrong - and unconstitutional.

The Court’s minority is right: the Constitution is no license for a business to discriminate.

Today’s ruling will move America backward.

There is also the question of whether this case should ever have been at SCOTUS. Watch Andrew Weissman explain why this case should not have been heard. 👇

"In this country, you cannot bring a case that is a hypothetical... There has to be a real dispute... This is somebody who, there was no real issue, there was no complaint. This wasn't even somebody who had opened up a business" - @AWeissmann_ w/ @NicolleDWallace pic.twitter.com/dNH07V0wgY

— Deadline White House (@DeadlineWH) June 30, 2023

The Supreme Court rejects Biden's plan to wipe away $400 billion in student loan debt.

WASHINGTON (AP) — A sharply divided Supreme Court on Friday effectively killed President Joe Biden’s $400 billion plan to cancel or reduce federal student loan debts for millions of Americans.

The 6-3 decision, with conservative justices in the majority, said the Biden administration overstepped its authority with the plan, and it leaves borrowers on the hook for repayments that are expected to resume by late summer.

Biden was to announce a new set of actions to protect student loan borrowers and would address the court decision later Friday, said a White House official. The official was not authorized to speak publicly ahead of Biden’s expected statement on the case and spoke on condition of anonymity.

The court held that the administration needed Congress’ endorsement before undertaking so costly a program. The majority rejected arguments that a bipartisan 2003 law dealing with student loans, known as the HEROES Act, gave Biden the power he claimed.

“Six States sued, arguing that the HEROES Act does not authorize the loan cancellation plan. We agree,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the court.

Justice Elena Kagan wrote in a dissent, joined by the court’s two other liberals, that the majority of the court “overrides the combined judgment of the Legislative and Executive Branches, with the consequence of eliminating loan forgiveness for 43 million Americans.”

Loan repayments are expected to resume by late August under a schedule initially set by the administration and included in the agreement to raise the debt ceiling. Payments have been on hold since the start of the coronavirus pandemic more than three years ago.

The forgiveness program would have canceled $10,000 in student loan debt for those making less than $125,000 or households with less than $250,000 in income. Pell Grant recipients, who typically demonstrate more financial need, would have had an additional $10,000 in debt forgiven.

Twenty-six million people had applied for relief and 43 million would have been eligible, the administration said. The cost was estimated at $400 billion over 30 years.

Advocacy groups supporting debt cancellation condemned the decision while demanding that Biden find another avenue to fulfill his promise of debt relief.

Natalia Abrams, president and founder of the Student Debt Crisis Center, said the responsibility for new action falls “squarely” on Biden’s shoulders. “The president possesses the power, and must summon the will, to secure the essential relief that families across the nation desperately need,” Abrams said in a statement.

The loan plan joins other pandemic-related initiatives that faltered at the Supreme Court.

Conservative majorities ended an eviction moratorium that had been imposed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and blocked a plan to require workers at big companies to be vaccinated or undergo regular testing and wear a mask on the job. The court upheld a plan to require vaccinations of health-care workers.

The earlier programs were billed largely as public health measures intended to slow the spread of COVID-19. The loan forgiveness plan, by contrast, was aimed at countering the economic effects of the pandemic.

In more than three hours of arguments last February, conservative justices voiced their skepticism that the administration had the authority to wipe away or reduce student loans held by millions.

Republican-led states arguing before the court said the plan would have amounted to a “windfall” for 20 million people who would have seen their entire student debt disappear and been better off than they were before the pandemic.

Roberts was among those on the court who questioned whether non-college workers would essentially be penalized for a break for the college educated.

In contrast, the administration grounded the need for the sweeping loan forgiveness in the COVID-19 emergency and the continuing negative impacts on people near the bottom of the economic ladder. The declared emergency ended on May 11.

Without the promised loan relief, the administration’s top Supreme Court lawyer told the justices, “delinquencies and defaults will surge.”

At those arguments, Justice Sonia Sotomayor said her fellow justices would be making a mistake if they took for themselves, instead of leaving it to education experts, “the right to decide how much aid to give” people who would struggle if the program were struck down.

The HEROES Act has allowed the secretary of education to waive or modify the terms of federal student loans in connection with a national emergency. The law was primarily intended to keep service members from being hurt financially while they fought in wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Biden had once doubted his own authority to broadly cancel student debt, but announced the program last August. Legal challenges quickly followed.

The court majority said the Republican-led states had cleared an early hurdle that required them to show they would be financially harmed if the program had been allowed to take effect.

The states did not even rely on any direct injury to themselves, but instead pointed to the Missouri Higher Education Loan Authority, a state-created company that services student loans.

Nebraska Solicitor General James Campbell, arguing before the court in February, said the Authority would lose about 40% of its revenues if the Biden plan went into effect. Independent research has cast doubt on the financial harm MOHELA would face, suggesting that the agency would still see an increase in revenue even if Biden’s cancellation went through. That information was not part of the court record.

A federal judge initially found that the states would not be harmed and dismissed their lawsuit before an appellate panel said the case could proceed.

In a second case, the justices ruled unanimously that two Texans who filed a separate challenge did not have legal standing to sue. But the outcome of that case has no bearing on the court’s decision to block the debt relief plan. (Associated Press).

More on the Court’s Ruling on Thursday against Affirmative Action.

Anita Hill.

Earlier this month, I asked Anita Hill about the possibility of the Supreme Court ending affirmative action. Here's what she told me. pic.twitter.com/GKcFUKKAb0

— Christiane Amanpour (@amanpour) June 29, 2023

Hakeem Jeffries.

Right-wing ideologues on the Supreme Court gutted reproductive freedom last year.

— Hakeem Jeffries (@RepJeffries) June 29, 2023

The very same extremists just obliterated consideration of racial diversity in college admissions.

They clearly want to turn back the clock.

We will NEVER let that happen.

We will never surrender.#SCOTUS

— Hakeem Jeffries (@RepJeffries) June 30, 2023

Heather Cox Richardson, historian at the University of Maine, Letters from an American…

“…in the past, when schools have eliminated affirmative action, Black student numbers have dropped off, both because of changes in admission policies and because Black students have felt unwelcome in those schools. This matters to the larger pattern of American society. As Black and Brown students are cut off from elite universities, they are also cut off from the pipeline to elite graduate schools and jobs.”

From Gabe Fleisher (Wake up to Politics) -  A courtroom fight over race in today’s America

A courtroom fight over race in today’s America

By Gabe Fleisher • 30 Jun 2023

(Photo by Gabe Fleisher)

(Photo by Gabe Fleisher)

Good morning! It’s Friday, June 30, 2023. I was at the Supreme Court on Thursday as the justices issued their historic ruling on affirmative action.

Three justices spoke during the session, reading aloud from their opinions. But, at times — as I’ll note — the justices’ words diverged notably from the opinions and dissents that were published. The below account, drawing on my written notes, will give you a rare glimpse inside the secretive Supreme Court chambers. Only 15 reporters were in the room to hear the justices, and we were not allowed to bring electronic devices. Audio of the session was not livestreamed and will not be made available until October.

When the Supreme Court ended race-based affirmative action in college admissions on Thursday, it was Chief Justice John Roberts who authored the landmark majority opinion for an ideologically divided court.

“The Harvard and UNC admissions programs cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause” of the Fourteenth Amendment, Roberts wrote, referring to the two schools that sparked the dispute before the justices.

“Both programs lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful end points. We have never permitted admissions programs to work in that way, and we will not do so today.”

But, sitting inside the courtroom, I was more struck by the exchange that played out after Roberts read from his opinion.

Generally, when the justices hand down their rulings, only the author of the majority opinion reads their views aloud. But any justice can speak if they so choose; on Thursday, two more decided to weigh in verbally: Clarence Thomas, concurring with the decision, and Sonia Sotomayor, pointedly dissenting.

Sotomayor’s dissent was the first to be read aloud since Elena Kagan did so in a gerrymandering case in 2019. (Although it is a rare event, that is partially because the justices did not announce opinions in-person during Covid.) Reading a concurrence from the bench is even more uncommon: a veteran Supreme Court reporter could only recall two other instances of it in the past 10 years.

“Although it’s not my practice to announce my separate opinions from the bench,” the normally taciturn Thomas explained, “the race-based discrimination against Asian-Americans in these cases compels me to do so today.”

While Roberts took only a few minutes to deliver the opinion of the court, the colloquy between Thomas and Sotomayor lasted nearly a half-hour. A difference in tone was also evident: while the chief justice spoke matter-of-factly — he seemed almost bored — his more uncompromising colleagues spoke with an obvious dose of added passion.

At times, it seemed Thomas and Sotomayor weren’t just discussing affirmative action: they were hashing out even deeper questions, about the level of post-racialism in the U.S. and what we owe our ancestors.

Their sharply worded exchange launched the court into the ongoing dispute over the role of race in 21st-century America, the same debate playing out simultaneously in school boards, on the campaign trail, and across the country.

Twice in his remarks, Thomas repeated a version of the same refrain, one that curiously does not appear at all in his written concurrence that was published: “This is not the 1860s or the 1960s,” he intoned, arguing that America had moved beyond its most discriminatory periods.

Sotomayor saw the U.S. differently. “Equality is an ongoing project,” she responded, asserting that “racial inequality persists” in today’s America.

In his written concurrence, Thomas criticized Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson — who authored a separate dissent, which she did not read — for depicting a country (in his words) in which “we are all inexorably trapped in a fundamentally racist society, with the original sin of slavery and the historical subjugation of black Americans still determining our lives today.”

But from the bench, Thomas seemed to apply that criticism further, speaking as much to his colleagues as to the fights over wokeness, critical race theory, and DEI raging beyond the courtroom’s walls: “Contrary to today’s narrative,” he said in-person, the country is not so racially ossified.

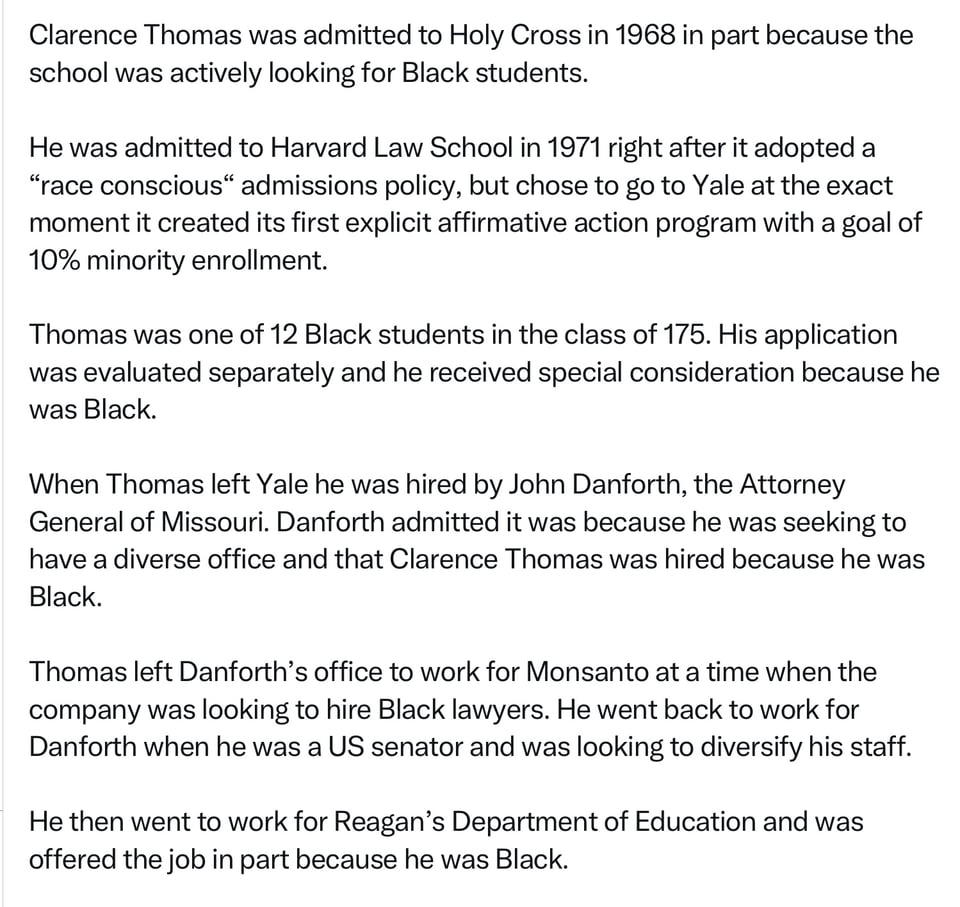

Thomas and Sotomayor, who sit next to each other on the bench, bring similar backgrounds but opposing ideologies to this debate. The court’s second Black and first Hispanic jurists, respectively, they both rose from relative poverty to attend Yale Law School. They are both — by their own accounts — beneficiaries of affirmative action, the programs benefitting Black and Hispanic students that were at the heart of their Thursday exchange.

But their journeys led them to very different conclusions. According to political scientists Andrew Martin and Kevin Quinn, who calculate the index of judicial ideology known as the Martin-Quinn Score, Thomas is the court’s most conservative justice; Sotomayor is its most liberal.

Thomas views affirmative action programs as unconstitutional for their invocation of race and fundamentally unfair to Asian-Americans. “Two discriminatory wrongs cannot make a right,” he said Thursday.

Sotomayor, meanwhile, praised such programs as opening doors to “young students of every race.” She said the court’s decision overturning them would have a “devastating impact.”

In comments that seemed reminiscent of the ongoing political fight over what history should be taught in schools, Thomas and Sotomayor both expounded on the messages that should be passed down to young people about the vestiges of slavery and segregation.

“Today’s 17-year-olds, after all, did not live through the Jim Crow era, enact or enforce segregation laws, or take any action to oppress or enslave the victims of the past,” Thomas said. “Whatever their skin color, today’s youth simply are not responsible for instituting the segregation of the 20th century, and they do not shoulder the moral debts of their ancestors. Our nation should not punish today’s youth for the sins of the past.”

Sotomayor, meanwhile, argued that America is “an endemically segregated society where race has always mattered and continues to matter.” In such a society, she added, “we are all responsible as a country for the effects of discrimination,” a line she left out of her published dissent.

Thomas suggested that such a mentality, contrary to “our colorblind Constitution,” consigns minorities to “permanent victimhood” status. The justice described that philosophy as “cancerous to young minds”; when he did so, it was hard not to think of Ron DeSantis, a combatant in the parallel fight in the political arena, who frequently rails against the “woke mind virus” in his speeches.

The barbs, delivered before a hushed courtroom — with a couple dozen lawyers and spectators watching intently — appeared personal at times. Thomas drew on his experiences growing up in the Jim Crow South; a line that appears as “the segregation of the 20th century” in his written concurrence became “the segregation many of us suffered in the 20th century” when speaking in-person. (His pointed comment that “the same skin color does not mean that we think or act alike” also seemed to draw on his experiences as a Black conservative.)

Although Roberts delivered the court’s formal opinion, it was Thomas who Sotomayor more frequently referred to on the bench. (The one time she did mention Roberts, citing his ruling in a previous case, the chief justice noticeably turned to look at her, seemingly in surprise.) Thomas cites “no evidence” to claim that affirmative action hurts Asian-Americans, she alleged; he “belies reality” by equating affirmative action advocates with historical segregationists who discriminated against minorities while professing to assist them.

Thomas did not look Sotomayor’s way any of the times that she invoked him. At one point during her oration, he leaned back in his chair and stared at the ceiling, rocking back and forth.

Justice Jackson, the court’s first Black female member, also sparred with Thomas in equally harsh terms, although only the written page. Thomas mentions Jackson’s separate dissent 18 times in his concurrence; Jackson’s opinion accuses him of an “obsession with race consciousness” in turn. Perhaps because she was recused from one of the two cases due to her role on Harvard’s board, Jackson did not read from her dissent aloud on Thursday. Instead, she stared straight ahead during the entire session, a pursed expression on her face.

There is good reason both Sotomayor and Jackson focused so heavily on Thomas. More than Roberts, an avowed moderate and institutionalist, it is often the arch-conservative Thomas who has set the pace for this latest iteration of the 6-3 Supreme Court.

As a recent Bloomberg Law article put it, Thomas has spent his 32-year career on the bench — he is the court’s most senior member — “laying down markers, spelling out his vision of the law in separate opinions.” Over time, on issues ranging from guns to abortion, those “outlier positions have slowly become the norm”; passages from his solo dissents and concurrences in past cases are now frequently lifted into majority opinions.

Even on Thursday, as he largely achieved the result on affirmative action he has long worked for, Thomas’ concurrence inched beyond Roberts’ opinion. The chief justice, writing for himself and his five fellow conservatives, did not explicitly overturn Grutter v. Bollinger, the court’s 2003 precedent upholding race-based affirmative action in college admissions.

But Thomas said he did. “The court’s opinion rightly makes clear that Grutter is, for all intents and purposes, overruled,” Thomas added, a declaration that lacks the force of law but will linger in history regardless.

Before concluding, both Thomas and Sotomayor again looked past affirmative action to make broader points about society. “The court today lives up to the promise of the Second Founding,” Thomas declared, arguing that a powerful step had been taken towards realizing Reconstruction-era ideals about America.

Sotomayor, though, painted the decision as contrary to the values of the current day. Urging colleges to continue using “all available tools to meet society’s needs for diversity in education,” the liberal justice approvingly noted that “diversity is now a fundamental American value.”

“Notwithstanding this court’s actions,” she added, “society’s progress toward equality cannot be permanently halted... The pursuit of racial diversity will go on.”

Then, she added one more rhetorical flourish, a kicker that does not appear in her dissent. “We shall overcome,” Sotomayor promised.

New York Times Editorial Board

In striking down affirmative action in higher education on Thursday, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority said it had to do so because the Constitution forbids any form of racial distinction. With a single opinion, the justices overturned decades of precedents that upheld race-conscious admissions policies as consistent with the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause and ignored the reality of modern America, where prejudice and racism endure.

As Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in dissent, the decision cements “a superficial rule of colorblindness as a constitutional principle in an endemically segregated society where race has always mattered and continues to matter.”

The result of Thursday’s decision means the end of a system that provided decades of opportunity for thousands of students who might otherwise have been turned away from some of the nation’s biggest colleges and universities. The effects will be felt nationwide, and soon. In states that have already banned affirmative action in higher education, the percentage of Black students has dropped, in some cases dramatically. Black enrollment at the University of Michigan was 4 percent in 2021, down from 7 percent in 2006 before Michigan voters prohibited the consideration of race in college admissions. The story is similar in California, despite that state’s intensive efforts to recruit more minority students by other means.

That this ruling has been long anticipated does not change the context in which it was handed down. For the second time in just over a year, the Supreme Court tossed out a longstanding precedent intended, however imperfectly, to expand basic rights and freedoms to a large group of Americans who had suffered under a legal system that treated them as second-class citizens. Last year it was women seeking the constitutional right to have an abortion; this year it is chiefly Black and Latino students who want a shot at the economic opportunity that can come from a college degree.

Why now? Nothing has changed in either case — not public opinion, not the underlying facts, not even the behavior of the two schools targeted in the court’s decision, which were both following the guidelines the Supreme Court set out in a previous ruling on affirmative action in 2003.

Only one thing has changed: the court’s membership. With their supermajority now firmly in charge, the Republican-appointed justices have had free rein to upend swaths of American law in order to achieve long-held goals of the conservative movement. Ending any form of racial consideration has long been high on that list, part of a continuing effort to pretend that racial inequality no longer exists — what Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson described in her dissent as a “let-them-eat-cake obliviousness” to the role of race in daily life.

It has been the special project of an indefatigable right-wing activist named Edward Blum, who for years has coordinated the legal challenges to affirmative action, including the current lawsuits, which targeted race-conscious admissions practices at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina.

Thursday’s ruling, written by Chief Justice John Roberts and joined by all of the Republican-appointed justices, takes a long time to make a simple — and simplistic — point: There is no real difference between the centuries of racial discrimination against Black people and targeted race-conscious efforts to help Black people. Both are equally bad, in this view.

The chief justice has long adhered to this view of race. As he wrote in a 2007 case striking down race-conscious state programs aimed at integrating public schools, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” It was a memorable line, because it flattered the commonly held belief that any race-based discrimination is not just wrong but unconstitutional.

The problem is that, as a matter of history, it’s not true. The 14th Amendment, ratified in the aftermath of the Civil War, was expressly intended to allow for race-conscious legislation, as Justice Sotomayor noted emphatically on Thursday. The same Congress that passed the amendment enacted several such laws, including the Freedmen’s Bureau Acts, which helped former slaves secure housing, food, jobs and education.

The bureau was an obvious and essential measure to remedy at least some of the harm that slavery inflicted on Black Americans. The first affirmative-action programs, a century later, had the same goal, only then it was necessary to address the decades of state-sanctioned discrimination against Black people that followed Reconstruction, and that continued to impose unique and specific hurdles to their ability to fully join American society. As President Lyndon Johnson said in a 1965 commencement speech at Howard University, “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘You are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair.”

And yet despite the success of affirmative action programs in raising minority enrollment, or more likely because of it, the pushback was immediate. Allan Bakke, a white man rejected by the medical school at the University of California, Davis, said he was the victim of racial discrimination and filed a lawsuit. In a complicated split opinion in the 1978 Bakke case, the Supreme Court allowed race to be considered in college admissions, but only for the purpose of increasing diversity on campus, not as a way to alleviate the long-term effects of discrimination.

The focus on diversity was an orchestrated compromisemeant to win over the court’s key swing justice, Lewis Powell. It worked, and yet at the same time it set the stage for affirmative action’s ultimate demise. By limiting it to a hard-to-define concept like diversity, the court opened the door to endless challenges. Some justices have asked, for example, why certain types of diversity mattered more than others. Why only racial diversity and not religious or political diversity?

But diversity — whether on campus, in business, or in government and society at large — remains a vital goal for any institution, and it will now be more difficult to achieve. The word is not a “trendy slogan,” as Justice Jackson wrote in her dissent. Diversifying medical schools by opening up the profession to Black physicians can save lives, she notes. Black infants, for example, are more likely to survive under the care of a Black doctor. Diversity also expands economic benefits and social understanding. A diverse student body, she wrote, means that “students of every race will come to have a greater appreciation and understanding of civic virtue, democratic values, and our country’s commitment to equality.”

What’s especially interesting in Thursday’s opinions is not where the justices disagree but where they agree: The Equal Protection Clause allows for race-conscious programs, as long as they are narrowly tailored to meet a compelling government interest. In fact, the opinion explicitly permits affirmative action in military academies, in what seems to be an acknowledgment that diversity in the armed forces remains a national priority. The real debate, then, is over exactly where to draw that line. What sort of harm is sufficiently clear and traceable to permit an exception to the 14th Amendment, and what isn’t? For nearly half a century, the court drew the line to permit affirmative action in higher education. On Thursday, it moved that line.

None of this is to deny the legitimate critique of affirmative action as it functions today. Unlike abortion rights, most Americans oppose race-based admissions programs for colleges, polls show. These programs have, for instance, been insufficient for addressing economic disparities, which are a crippling barrier to millions of Americans of all colors.

This and other shortcomings require their own solutions. This ruling against Harvard and University of North Carolina should be a call to action, for private and state universities alike, to create new paths to ensure that qualified students can find opportunity on their campuses. More evidence is needed around whether the most commonly proposed alternatives — giving a leg up to students from lower socioeconomic groups, for example, or admitting the top 10 percent of students from each high school in a state — boost minorities into better jobs and more stable lives.

Many schools, of course, already engage in one particularly insidious form of wealth-based affirmative action: legacy admissions. The children of alumni — who are overwhelmingly white — enjoy a far better chance than other applicants of getting accepted to the nation’s top colleges and universities, which, as this board has argued, constitutes “a form of property transfer from one generation to another.” It has a far larger impact on the racial and socioeconomic makeup of student bodies than race-based affirmative action ever has. At Harvard, an estimated 14 percent of students, most of whom are white, are there at least in part because of a legacy. Reducing or eliminating this practice could create new opportunities for all kinds of students who normally don’t have a chance of getting into a top school.

It’s nice to imagine an America where all people are treated the same, regardless of the color of their skin, but that is not the nation we live in today or ever have lived in. “Our country has never been colorblind,” Justice Jackson wrote. “Deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life.”

This is a genuinely difficult task, but the solution is not to pretend that we have suddenly become colorblind. Any meaningful effort should take race into account. That’s not only permissible under the Constitution; it’s the only way it has ever succeeded.

Heroes.

Heroes.

So sad.

So sad.

____________________________

Ginni and Clarence: A Love Story

How they saved one another, raged against their enemies, and brought the American experiment to the brink.

By Kerry Howley

Clarence Thomas,” says Ginni Thomas in a 2018 installment of her long-running Daily Caller interview series on the subject of leadership, “you’re the best man walking the face of the earth.”

He chuckles. They sit a few feet apart in a small room near a clock, a bookshelf full of file folders, a plant in a wicker basket.

“It’s an honor to interview you.”

“Well, I’m really stressed out about this interview,” he says, not smiling, then smiling, then laughing. Halfway through their time together, Clarence Thomas is talking about coming from a place where many of the adults around him were illiterate. He’s talking about the deep pleasure he finds in old books, “like Christmas every day,” the sense of gratitude for this knowledge denied his aunt, mother, grandfather.

“Now I know you think I’m a little different,” he says. “And I am. But … you get to read Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson — many people kind of roll their eyes — ”

Clarence, perhaps reading the lack of interest in Ginni’s eyes, starts laughing.

“But just think of all the people,” he says, motioning forward with his hand in a Clintonian gesture of explanation, “who were around him. Whether it was Edmund Burke or Adam Smith.” He laughs again. “I mean, wouldn’t you want to read Boswell’s Life of Samuel” — he can hardly get the words out now, he’s laughing so hard — “Johnson?”

Ginni laughs quietly.

“I’ll put it on my list, Justice,” she says with a little flick of the wrist and coy look into the distance.

“I’ll lend you my copy,” he says with a straight face.

“As long as you underline it for me.”

He loses it.

“Okay,” she says, ready to move on with her list of questions.

“What about,” he says, leaning in, very serious now, “Wealth of Nations?”

“Just — ” she says.

And he loses it again, a high-pitched laugh that tilts him forward in his chair.

“I have a life to live,” she says, sighing.

“Okay,” she says. “All right.”

“Oh God,” he says, “you make me laugh.”

Ginni has brought questions. She’s trying to get back on track. There’s more to mine on the subject of leadership.

“Um,” she asks, “if someone asks for your advice when they’re getting married, what would you suggest?”

“I keep a sign on my desk,” he says: “Don’t make fun of your wife’s choices, you were one of ’em.”

He’s laughing again.

“Thank you. I really appreciate that. And that’s so true.”

“Okay. What — ”

“Plus I love my wife. My wife cracks me up … You and I are very different. You don’t read The Life of Samuel Johnson, for example.”

And they’re laughing again.

“Exactly,” she says.

“Oh God,” he says. “I love you.”

There is a certain rapport that cannot be manufactured. “They go on morning runs,” reports a 1991 piece in the Washington Post. “They take after-dinner walks. Neighbors say you can see them in the evening talking, walking up the hill. Hand in hand.” Thirty years later, Virginia Thomas, pining for the overthrow of the federal government in texts to the president’s chief of staff, refers, heartwarmingly, to Clarence Thomas as “my best friend.” (“That’s what I call him, and he is my best friend,” she later told the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol.) In the cramped corridors of a roving RV, they summer together. They take, together, lavish trips funded by an activist billionaire and fail, together, to report the gift. Bonnie and Clyde were performing intimacy; every line crossed was its own profession of love. Refusing to recuse oneself and then objecting, alone among nine justices, to the revelation of potentially incriminating documents regarding a coup in which a spouse is implicated is many things, and one of those things is romantic.

“Every year it gets better,” Ginni told a gathering of Turning Point USA–oriented youths in 2016. “He put me on a pedestal in a way I didn’t know was possible.” Clarence had recently gifted her a Pandora charm bracelet. “It has like everything I love,” she said, “all these love things and knots and ropes and things about our faith and things about our home and things about the country. But my favorite is there’s a little pixie, like I’m kind of a pixie to him, kind of a troublemaker.”

A pixie. A troublemaker. It is impossible, once you fully imagine this bracelet bestowed upon the former Virginia Lamp on the 28th anniversary of her marriage to Clarence Thomas, this pixie-and-presumably-American-flag-bedecked trinket, to see it as anything but crucial to understanding the current chaotic state of the American project. Here is a piece of jewelry in which symbols for love and battle are literally intertwined. Here is a story about the way legitimate racial grievance and determined white ignorance can reinforce one another, tending toward an extremism capable, in this case, of discrediting an entire branch of government. No one can unlock the mysteries of the human heart, but the external record is clear: Clarence and Ginni Thomas have, for decades, sustained the happiest marriage in the American Republic, gleeful in the face of condemnation, thrilling to the revelry of wanton corruption, untroubled by the burdens of biological children or adherence to legal statute. Here is how they do it.

Things About Home

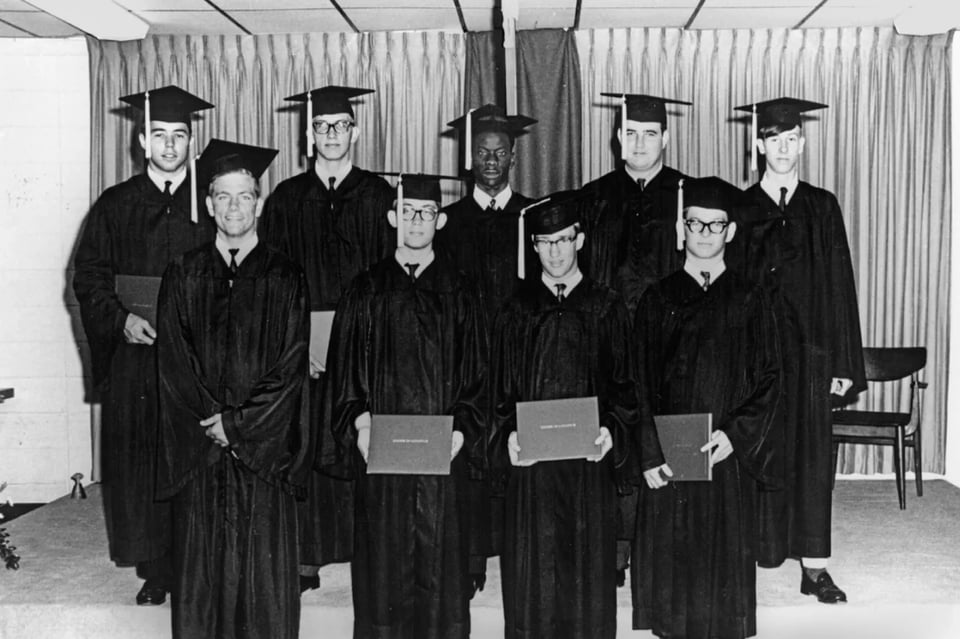

Clarence Thomas, the only Black graduate in the 1967 class of St. John Vianney, with his fellow graduates.

My husband’s childhood was so unlike mine,” Ginni Thomas once said. “I know when I first went down to Pin Point I said, ‘Clarence, I can’t understand a word that they just said’ … I just try to listen and smile.” Numerous attempts have been made to diminish the lonely hardship into which Clarence Thomas was born — he was “middle class,” one will read; biographers cannot find corroboration on various slights he claims to have suffered — and yet the objective circumstances suggest a material and emotional deprivation that renders all of this at best irrelevant. He emerged from that childhood not a conventional conservative in any sense, but something closer to what Stephen Smith, Thomas’s first Black clerk and the author of “Clarence X?,” calls Black nationalist.

“There is nothing you can do to get past Black skin,” Thomas once told Juan Williams. “I don’t care how educated you are, how good you are at what you do — you’ll never have the same contacts or opportunities, you’ll never be seen as equal to whites.” His is a fundamentally fatalistic vision of white liberals, whose every attempt to “help” is pure vanity, a more dangerous, because more dishonest, extension of the white supremacy they profess to deplore. His views on school busing are instructive: “I wouldn’t have gone into South Boston. It would have been taking my life in my hands for me to do so. Why, then, were innocent children being made to do what a grown man feared?” This is not a question earnestly posed, because Thomas has in countless speeches articulated the motives of white liberals disrupting Black life: They act to assuage white guilt, to improve the aesthetics of the ruling class, to stoke the delicate self-conception of those who would never willingly cede power, all of it in service to a supremacist status quo. He prefers, he has said, the directness of southern racism to the subtlety of northern condescension.

The details are by now familiar: Thomas, abandoned by his father, raised in isolated coastal Georgia, where he was teased by lighter-skinned Black children for his particularly dark skin. The one-room, one-lightbulb cottage; the local dialect, Geechee, for which Clarence was also teased.

Each episode of Clarence’s young life would showcase a distinct American horror. His little brother accidentally burned down the cottage, and the boys moved to Savannah. “Urban squalor,” he called these living conditions, “hell.” At night, his mother and brother shared a bed; he slept, cold and hungry, on a chair. Unable to keep them warm and fed, Leola Williams begged her father to take them in. “The damn vacation is over,” he told the boys, though the boys did not know what vacation he was talking about. “He meant to control every aspect of our lives,” writes Thomas in My Grandfather’s Son, a book in which he describes said Grandfather as both a looming “dark behemoth” subjecting them to vicious punishment for the transgression of arbitrary rules and “the greatest man I had ever known” in the space of a page. Daddy, as they called him, filled the boys’ every hour with work and refused them work gloves when their hands blistered. “He never praised us,” Thomas writes, “just as he never hugged us … In his presence there was no play, no fun, and little laughter.”

Clarence was living in his grandfather’s house the year his future wife was born. Virginia Lamp grew up in a lakeside home the Omaha World-Heraldonce called “a resort residence” and Virginia’s mother described as “away from all the rush of city life,” which is to say in a 142-home development her developer husband had established 30 minutes outside Omaha, built around two ersatz lakes he had dredged himself. The carpeting, we learn from the World-Herald’s strangely advertorial account of the home’s interior, was chosen specifically to “cope with sand that might be brought in from the beach,” and while the drive might seem a burden, the family found it salutary to be far removed from the apparent stress of central Omaha. Entertaining is easy, Marge Lamp, Ginni’s mother, told the World-Herald in 1969, when one has both a sailboat and a motorboat available for guests.

Ginni, the youngest of four, attended Westside High School, an extremely white institution in a smaller district separate from Omaha’s larger school system. Her childhood was, to an astonishing degree, structured to protect her from the realities her future husband had endured, and yet here also loomed some unseen enemy, an invisible threat to the existence of easy entertaining. “Positive information is the best defense against ridicule of our flag, our Christian heritage, our free enterprise system and our form of government,” Marge Lamp wrote in a 1969 letter to the editor, leaving the flag ridiculers unnamed.

At age 12 Ginni boarded a chartered plane for Washington, D.C., having been selected as a page for the GOP Women’s Conference, where she would sport a sash and a top hat; partisan costuming would continue to be a theme throughout her life. Her childhood was social where Clarence’s had been isolated, a succession of parades and rallies and fundraisers, the sense that the world could, though determined voluntarism, be changed. Ginni’s mother supported Phyllis Schlafly’s crusade against the Equal Rights Amendment, and hosted at her home, there on the sandproof carpet, like-minded nationally known speakers, such as Frederick Schwarz of the Christian Anti-Communism Crusade. Marge Lamp, or as she put it in her campaign literature, “Mrs. Donald G. Lamp,” ran for state legislature under the theme of “common sense” and told the paper she’d commute to Lincoln and be back home at night, such that her husband would not miss many meals. She was, according to friend and former congressman Hal Daub, a positive, active, affable, civic-minded presence in Omaha, one-half of a marriage of equals. Her best campaigners, she said, were her children. She lost, but she had passed on something in the attempt.

“That was my first real campaign,” Ginni told a reporter in 1974. She was a high-school student canvassing for Republicans in the age of Watergate, which, she assured the reporter, “was just Nixon and his people, not the Republican Party.” Why campaign when you’re too young to vote? “Because the party needs us,” she said, sloshing through the rain to deliver more talking points. Ginni was a compulsive joiner. As a “warrior woman,” she donned a shield and cheered on the football team. Daub, a centrist Republican, would later employ her in D.C. She stood out in his office as social, eager, and unusually knowledgeable — “a wonk.”

In the spring of 1986, Clarence was a 37-year-old divorced single father and one of D.C.’s most eligible bachelors according to Jet magazine, which we can be fairly certain Ginni did not read. He was the head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a rise from poverty that a traditional conservative would describe as a rags-to-riches individualist American triumph, but this is neither Clarence Thomas’s experience nor the story he chooses to tell.

There had been, after the brief and defining comfort of his Black Catholic elementary school, a tour of white institutions where Clarence was made to endure a succession of racist humiliations. He was one of only two Black children in his high-school seminary, which is to say constantly surrounded by white adolescent boys. “Smile so we can see you, Clarence,” he recalls one saying in the dark. He dropped out of his college seminary after he heard a classmate celebrating the death of Martin Luther King Jr. As an undergraduate at Holy Cross, he listened to records of Malcolm X speeches, helped found a Black Student Union, and nearly dropped out in protest of racially motivated mistreatment. He was never so invested in student life at Yale Law, where the distance between himself and his classmates appeared the difference between Pin Point and Greenwich. “I felt the difference in my bones,” he writes. “I was among the elite, and I knew that no amount of striving would make me one of them.” What other Yale Law student, gearing up for a summer home, was “sick with worry” about the “frightening prospect” of driving through the South in an unreliable old car past a Klan-sponsored billboard? Who else had to endure the strange looks of white mechanics inspecting the failing car, a “bad night’s sleep” in a strange motel when no one could fix it, and rescue, finally, from his brother?

As the head of the EEOC, burdened with debt, Thomas was a man conspicuously lacking generational wealth. He was still broke. American Express cut him off for failure to pay his bills. He could not access a credit card, and so when he did official business, incredibly, his secretary had to book him only in hotels that took cash. His apartment was full of cockroaches. He was overcome with loneliness, “lower than a snake’s belly,” and, according to his friend Armstrong Williams, liable to “bore women to death” on dates.

It was not on a date that he met 29-year-old Virginia Lamp but at an intimate roundtable on affirmative action, or, as Ginni recently put it, on the subject of “how long America needs race-preference policies to get over slavery.” Midge Decter (or “Mrs. Norman Podhoretz”) introduced Thomas to Ginni, who was then a labor lobbyist for the Chamber of Commerce. The two of them shared a cab back to the airport.

“I have some Black female friends I’d really like to put together with you,” Ginni said. Clarence laughed and said he wasn’t interested. The next time he saw her, she was soaking wet, having trudged through the rain to attend a D.C. event intended to introduce EEOC chairman Clarence Thomas to “the business community.”

They shared a professional, polite lunch on K Street; he never considered dating her, he wrote later, because he had “more than enough problems” and didn’t need to add dating a white woman to the list. Yet someone must have been interested in more, because a few weeks later, they took in an early-afternoon showing of Short Circuit, which is not the kind of thing one does with just another member of the business community. Short Circuit involves a winsome military robot who gains sentience, flees its Army pursuers, and wins freedom from its government minders by building a decoy of itself. Clarence laughed the whole way through, and Ginni laughed, just as she would decades later, at the spectacle of him laughing. “I left that dinner smiling like I’d never smiled,” Ginni said of their post–Short Circuit meal. “I was in love with this guy.”

There was an unsettledness about Ginni, projects started and dropped. She enrolled at Mt. Vernon College in D.C. and transferred to the University of Nebraska to be closer to her boyfriend, a premed student enrolled at Creighton. She then transferred to Creighton, her third undergraduate institution, presumably to be closer still, and became, naturally, Nebraska’s College Republican chair. Her parents announced her engagement to a med student, though the two never married. She worried she would never find a husband who would support her ambition. She went to law school and dreamed of representing Nebraska in Congress.

She and Clarence walked along Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, where people stared, and the couple talked about the people staring. She seemed to him uncynical, unspoiled, a person who believed in things. “She was a gift from God that I had prayed for,” Clarence said. “And then I was iffy, because I started questioning God’s package. You know, like what are you doing? You pray for God to send you someone, he sends you someone, and you say, ‘Oh, but she’s white’ or ‘She’s younger.’ He’s sent you someone. What are you talking about?”

Ginni was, according to Clarence, “willing to fight anybody, including friends and family, who objected to the match.” (“I didn’t know what to think,” was Marge Lamp’s reaction to her daughter dating a Black man.) Less than a year after the early showing of Short Circuit, they were married. Four years after that, George H.W. Bush announced his choice for nomination to the Supreme Court. “It’s going,” Ginni said, “to be fun.”

Love Things

Virginia Thomas, then Virginia Lamp, poses as a “warrior woman” during her time at Westside High School in Omaha, Nebraska.

Virginia Thomas, then Virginia Lamp, poses as a “warrior woman” during her time at Westside High School in Omaha, Nebraska.

Strange Justice, a 1994 book by Jane Mayer and Jill Abramson, is astonishingly well sourced on the subject of Clarence Thomas’s relationship to “freak of nature” pornography. Here is a fellow Yale Law student describing “one of the crudest people I have ever met … profane, scatological and graphic,” given, according to Pulitzer Prize winner and Holy Cross classmate Edward P. Jones,* to using language that “would have reduced other people to tears.” An acquaintance from Yale remembers him carrying porn in the back pocket of his overalls and offering detailed descriptions of X-rated movies he had seen in downtown New Haven. Here we have the proprietor of Graffiti, a video store then near Dupont Circle, describing the kind of movies to which Thomas was drawn, at a time when adult-video connoisseurs were regularly engaging with characters like Long Dong Silver, whose 18-inch apparently prosthetic penis has since been recast as an early, heartening example of body positivity. Here a woman describes visiting Clarence in 1982 and encountering, on nearly every wall of the apartment of the chairman of the agency tasked with setting guidelines on workplace sexual harassment, posters of naked women. Thus it was that when inside the Caucus Room in the Russell Senate Office Building before the all-white, all-male Senate Judiciary Committee, Anita Hill described a man picking up a can of soda and asking “Who has put pubic hair on my Coke?” she sounded, to many in middle America, deranged, and to Clarence Thomas’s intimates, something else altogether. “I didn’t know what to think until I heard the Coke can story,” Gordon Davis, a friend of Thomas’s from Holy Cross, told Mayer and Abramson. “When I heard that, I knew he’d say stuff like that.” Confirms Edward P. Jones: “The Coke can thing did it for me.”

One person for whom the Coke-can thing did not appear to resonate was Virginia Thomas, who took these proceedings to be evidence of a presence she’d been hearing about all her life: a vast and vulgar left-wing conspiracy. The hearings had begun normally; Clarence Thomas was questioned as to his opinions and insisted that those opinions were utterly irrelevant to his unbiased application of legal precedent, and politicians on both sides pretended to believe him. He had “no agenda” on Roe v. Wade;he had an “open mind” about abortion; it would “totally undermine and compromise” his capacity as a judge to sit on any cases he had “prejudged.” He was simply an umpire, an objective arbiter of the straight truth, but a humble foot soldier of settled law as it had been defined prior to his time. News of Anita Hill’s accusations was delivered via FBI agents at Thomas’s kitchen table. Senate Judiciary Committee leader Joseph Biden called Thomas to discuss the hearings over which he would preside, and Clarence turned the receiver toward Ginni so she could hear. As Clarence tells it:

“As he reassured me of his goodwill, she grabbed a spoon from the silverware drawer, opened her mouth wide, stuck out her tongue as far as she could, and pretended to gag herself.”

This was an account of events in 1991 in an autobiography published in 2007, when Clarence Thomas was a sitting justice on the Supreme Court. That he cares to share this detail at such cinematic length (“gagged herself with a spoon” would have been more economical but less visual) suggests immense pride in his wife. This is the Ginni he loves, the one engaged by conflict, loyal and funny and true.

There had been not long before a time when Ginni’s intensity was a problem. “She went through this pattern where every guy she was dating was her guru,” said someone familiar with both Thomases. But there had also been actual gurus. Lifespring was a group some people called a “human potential organization” and other people called a cult. (“Are our people enthusiastic, intense and emotional? Yes,” the group’s vice-president said in response to this accusation.) Ginni had recently failed the bar exam. There were “trainings” in Rosslyn and Capitol Hill; in one, participants were made to remove their clothes, listen to “The Stripper,” and insult one another’s bodies. A guy you call in this kind of situation spent eight hours at Hamburger Hamlet in Georgetown deprogramming her. When she left the cult, she became deeply involved in a group focused on anti-cultism.

Ginni did not doubt her husband when a young woman accused him of describing rape scenes at work. In fact, reports Clarence, she “loved me more than ever.” Weren’t these accusations just more evidence that she had landed the ideal man, an object of crazy-making desire? “In my heart,” she said later, “I always believed she was probably someone in love with my husband and never got what she wanted.”

By all accounts, at this point, Clarence Thomas simply fell apart. “I lay across the bed and curled up in a fetal position,” he writes. “He was,” Ginni said later, “debilitated beyond anything I’d ever seen in my life.” “I have never had an experience like that,” former senator John Danforth later said. “Ever. Still haven’t. Because he was a broken man. He was just broken.” It was “spiritual warfare,” Virginia said, “good versus evil.”

It is hard to see how Clarence Thomas would have extricated himself from the fetal position without Ginni, who closed the blinds and put on Christian music and invited couples over to pray and called a neighbor to come over and give Clarence a haircut, which she did. He got up at one in the morning the night before the hearing and looked over his papers, suggestions on how to respond, and was, according to Ginni, “really confused.” She cleared the table for him. She turned on his computer. He wrote his speech on a notepad. She typed it up.

As they walked down the hallway to the Caucus Room, women standing against the walls clapped for him. They were from Phyllis Schlafly’s Eagle Forum, there to bear him up.

“Who are they?” Clarence asked.

“They’re angels,” Ginni said.

She watched the proceedings in rage, “the wrath of anger coming out of my eyes.” Why wasn’t the conversation about his heroism? Where was the celebration for obstacles he had overcome? “My name has been harmed,” he said. “My integrity has been harmed. My character has been harmed. My family has been harmed. My friends have been harmed. There is nothing this committee, this body, or this country can do to give me my good name back. Nothing.”

When the vote was called, according to Virginia’s account, Clarence was in the shower; Clarence says he was in the bath. Both say Virginia ran up to tell him he had become a justice. He “just shrugged,” according to her. According to him, his response was “Whoop-dee damn-doo.”

For almost seven years after the hearings, Thomas stayed silent during oral arguments, a silence that he sometimes explained as an aversion to “hyperactive” grandstanding (“We look like the Family Feud”) and sometimes to his childhood speaking Geechee, but that looked, to many people, like disengagement: Whoop-dee-damn-doo. He went to work, day to day, a Supreme Court justice who still owed college loans. For a man not given to lazy, reflexive patriotism, there was no great narrative moment of breaking through into a world denied him.

There had been a day when Clarence returned to his grandfather’s house with his own small son, Jamal, and left him there for a while. When he returned, he found “five or six open boxes of cereal, all of them presweetened brands.” When he had been a child, living with his disciplinarian grandfather, “the idea of opening more than one box at a time was unthinkable.” He asked why Jamal had been allowed to open so many boxes. Jamal had wanted the prizes in the cereal, his grandfather said, to Clarence’s pained and enduring astonishment, and so together they opened all of them. Why, Clarence asked, had this extravagance been tolerated? “Jamal,” his grandfather said, “is not my responsibility.”

This is an odd moment to share for an author who perceives himself as writing hagiography, but it is of a piece with the rest of the work, which is an account, across time, of loneliness, persistent racism, and grievances both justified and otherwise. The house where his ancestors were enslaved, he notes acidly, became a bed-and-breakfast billed as “a perfect honeymoon hideaway.” Thomas’s loyalty, repeatedly expressed, is not to the grandfather who denied him affection, or the country that abandoned him to poverty, but to the woman he “needed … more than anyone,” the woman who did not doubt him when doubt was merited, the woman who handed him a towel as he emerged exhausted from the bath, or perhaps the shower, a Supreme Court justice. She was “as dear and close a human being as I could have ever imagined having in my life.” They had been through a “fiery trial” and emerged “one being — an amalgam.”

Things About Our Country

Ginni and Clarence during the confirmation hearings for his Supreme Court nomination in 1991

It wasn’t normal for the wife of a Supreme Court justice to give a full, intensely personal, and aggrieved account of the confirmation process and her husband’s attendant breakdown to People magazine, complete with posed pictures of them in their apartment — here casually reading a Bible together on the couch, here drinking coffee in the kitchen, here holding hands amid a bunch of binders on the floor — but from the very beginning Ginni and Clarence Thomas would appear to have no particular interest in decorum. In 1994, Clarence Thomas, successor of Thurgood Marshall on a Court steeped in “formality, courtesy, and dignity,” according to its Historical Society, presided over and hosted Rush Limbaugh’s third wedding, to a former aerobics instructor he met on CompuServe, at the Thomases’ home in Fairfax Station. Thomas had told the nation he couldn’t get his reputation back; he evidently did not care to try.

He stopped reading the newspaper. Their new home was invisible from the street. Clarence did not want more children, and Ginni had to accommodate this choice. It was her idea that they take in Clarence’s grandnephew, whose father was in prison; actually, she would have taken in all three siblings had their mother allowed it. They did not enter the broader social life of D.C. available to Supreme Court justices; they never would. The hearings confirmed something Clarence had long suspected. Southern racists were rattlesnakes. At least you heard them coming. “You know,” Clarence said, “where they stand.” New England liberals were water moccasins; just as deadly, and silent until they struck. He preferred people who didn’t smile through their hatred.

And yet Ginni’s new life as political spouse entailed precisely this, smiling as she met people for whom she felt only revulsion. “Wow,” she told The Wall Street Journal after she met Hillary Clinton, “now I have to, in my role, be respectful and cordial and courteous.” She seemed to have given up on the idea of being a representative for Nebraska. “I’m kind of stuck here,” she told the Journal, but there was lots one could do to further the cause in D.C. One could, on behalf of two House Republicans, send out a memo to House committees asking for “examples of dishonesty or ethical lapses in the Clinton administration,” a memo so objectionable in its stark partisanship that Democrats blew it up and posted it on an easel. During a hearing on a Clinton ethics controversy, Virginia Democrat Jim Moran openly objected to the presence of “Mrs. Clarence Thomas in that bright-blue dress.” Later that day, in an elevator, Ginni showed Moran a recently published book called Everything Men Know About Women. The pages of the book are blank. “This is about you,” she said.

Another man might have been embarrassed. Clarence called his wife at work and sang verses of “Devil With a Blue Dress On.” “Troublemaker” was what she called herself, a puckish spin on her decadeslong habit of creating the appearance of corruption. “Did the Missus Go Too Far?” read a typical headline in the Chicago Tribune. The missus did not go too far, she later said, because she was in the “political lane” and he in the “legal lane.” “I kind of zone out when it comes to legal issues,” she told the January 6 committee, perhaps the most relatable thing she has ever said. They simply would not talk about it.

They wouldn’t talk about it, specifically, in their used 40-foot Prevost motor coach, purchased in 1999 and taken to two dozen states in these two decades. The motor coach in which they did not discuss work was their favorite subject of conversation. (“Anybody ever tell you you look like Clarence Thomas?” he was asked at a Flying J.) This was the public identity they would allow, and it was not inaccurate: a couple who adored the company of one another making camp in RV parks in Michigan as relief from the stress of Washington. That the Thomases’ appreciation for middle-class travel is useful PR does not make it untrue, but as with all PR, something goes unsaid. They did not, neither in myriad public fora nor in legally required paperwork, mention various travels by yacht and private jet.

Harlan Crow, the Republican activist and billionaire son of a man whose company Forbes once called “the largest landlord in the United States,” says that he and Clarence Thomas share an interest in the virtue of “humility.” He and Clarence are good friends — even better friends than Harlan is with George W. Bush, he says — which explains the jet, and the yacht, and the $19,000 Bible once owned by Frederick Douglass, and the 1,800 pounds of bronze cast in the shape of Clarence’s favorite teacher and placed at a cemetery in New Jersey. Harlan Crow bought Thomas’s mother’s house, installed a gate and fixed the roof, and allowed her to continue living there. Clarence sent his adopted grandnephew to private school, and Crow paid roughly $100,000 in tuition; the president of a group of RV enthusiasts paid for $5,000 more. There was $150,000 to rename a wing of the Savannah library, another $105,000 to have him commemorated at Yale, millions on a museum in Pin Point. Ginni Thomas started a consulting firm with $550,000, $500,000 of which had been Harlan’s. In a Washington Examiner story celebrating Clarence’s Everyman RV trips, Clarence is pictured beside his motor home, wearing what reporters at ProPublica discovered to be a custom polo shirt Harlan Crow gifted guests on luxury vacations. Twenty times he failed to report Ginni’s income.