Monday, June 19, 2023. Juneteenth. Annette’s News Roundup.

I think the Roundup makes people feel not so alone.

To read an article excerpted in this Roundup, click on its blue title. Each “blue” article is hyperlinked so you can read the whole article.

Please feel free to share.

Invite at least one other person to subscribe today! buttondown.email/AnnettesNewsRoundup

_________________________

Juneteenth 2023.

Some updates and happenings around the nation connected to Juneteenth, the federal holiday in the United States commemorating the emancipation of enslaved African Americans.

Deriving its name from combining June and nineteenth, it is celebrated on the anniversary of the order, issued two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation by Major General Gordon Granger on June 19, 1865, proclaiming freedom for slaves in Texas.

Originating in Galveston, Juneteenth has since been observed annually in various parts of the United States, often broadly celebrating African-American culture.

The day was first recognized as a federal holiday in 2021, when President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Actinto law after the efforts of Lula Briggs Galloway, Opal Lee, and others. (Source. Wikipedia).

The White House hosted its first-ever #Juneteenth concert in honor and recognition of the newest federal on the South Lawn of the White House Tuesday, June 13, 2023.

Another beautiful, *historic* day as @VP powerfully speaks on #Juneteenth2023. Many thought they would never see our First, Black woman Vice President Kamala Devi Harris share the stage with Opal Lee, "grandmother of Juneteenth." That day arrived. 1/2 pic.twitter.com/eespe2kvuL

— silverprincess💛 (@marsha_vivinate) June 14, 2023

Big news earlier today at @USNatArchives when Dr. Colleen Shogan, Archivist of the United States, announced plans to have the Emancipation Proclamation on permanant display in the Rotunda at the National Archives Museum.https://t.co/gqbYRTxM2I https://t.co/bvQk2akG0T

— US National Archives (@USNatArchives) June 17, 2023

Thousands queue to see the Emancipation Proclamation and General Order No. 3.

Juneteenth weekend gave visitors to the National Archives a chance to see the historic documents, which are rarely displayed because they are fragile

Touch 👇 to watch.

Juneteenth as a federal holiday is meant to breathe new life into the very essence of America.

— President Biden (@POTUS) June 17, 2023

To make sure all Americans feel the power of this day and the progress we can make for our country.

Earlier this week, I felt that power at the White House. pic.twitter.com/Ogo6SBvZBA

The first Juneteenth, this month 1865: pic.twitter.com/s9XVbhm0pH

— Michael Beschloss (@BeschlossDC) June 17, 2023

Texas Governor @GregAbbott_TX chose the weekend of #Juneteenth to veto a bill to establish a Sickle Cell Registry: https://t.co/pPcjv5fpYX

— Leah McElrath (@leahmcelrath) June 17, 2023

Yesterday, I was thrilled to join @POTUS for the White House Juneteenth Concert with Americans from all walks of life, including Ms. Opal Lee, the grandmother of Juneteenth. By celebrating Juneteenth, we celebrate one of the founding principles of our nation: freedom. pic.twitter.com/rviY86Joy3

— Vice President Kamala Harris (@VP) June 14, 2023

A beginner's guide to Juneteenth: How can all Americans celebrate?

People who never gave the holiday on June 19 more than a passing thought may be asking themselves, is there a “right” way to celebrate Juneteenth?

For beginners and those brushing up history, here are some answers:

IS JUNETEENTH A SOLEMN DAY OF REMEMBRANCE OR MORE OF A PARTY?

It just depends on what you want. Juneteenth festivities are rooted in cookouts and barbecues. In the beginnings of the holiday celebrated as Black Americans’ true Independence Day, the outdoors allowed for large, raucous reunions among formerly enslaved family, many of whom had been separated. The gatherings were especially revolutionary because they were free of restrictive measures, known as “Black Codes,” enforced in Confederate states, controlling whether liberated slaves could vote, buy property, gather for worship and other aspects of daily life.

Others may choose to treat Juneteenth as a day of rest and remembrance. That can mean doing community service, attending an education panel or taking time off.

The important thing is to make people feel they have options on how to observe the occasion, said Dr. David Anderson, a Black pastor and CEO of Gracism Global, a consulting firm helping leaders navigate conversations bridging divides across race and culture.

“Just like the Martin Luther King holiday, we say it’s a day of service and a lot of people will do things. There are a lot of other people who are just ‘I appreciate Dr. King, I’ll watch what’s on the television, and I’m gonna rest,’” Anderson said. “I don’t want to make people feel guilty about that. What I want to do is give everyday people a choice.”

WHAT IF YOU’VE NEVER CELEBRATED JUNETEENTH?

Anderson, 57, of Columbia, Maryland, never did anything on Juneteenth in his youth. He didn’t learn about it until his 30s.

“I think many folks haven’t known about it — who are even my color as an African American male. Even if you heard about it and knew about it, you didn’t celebrate it,” Anderson said. “It was like just a part of history. It wasn’t a celebration of history.”

For many African Americans, the farther away from Texas that they grew up increased the likelihood they didn’t have big Juneteenth celebrations regularly. In the South, the day can vary based on when word of Emancipation reached each state.

Anderson has no special event planned other than giving his employees Friday and Monday off. If anything, Anderson is thinking about the fact it’s Father’s Day this weekend.

If I can unite Father’s Day and Juneteenth to be with my family and honor them, that would be wonderful,” he said.

WHAT KIND OF PUBLIC JUNETEENTH EVENTS ARE GOING ON AROUND THE COUNTRY?

Search online and you will find a smorgasbord of gatherings in major cities and suburbs all varying in scope and tone. Some are more carnival-esque festivals with food trucks, arts and crafts and parades. Within those festivals, you’ll likely find access to professionals in health care, finance and community resources. There also are concerts and fashion shows to highlight Black excellence and creativity. For those who want to look back, plenty of organizations and universities host panels to remind people of Juneteenth’s history.

ARE THERE SPECIAL FOODS SERVED ON JUNETEENTH?

Aside from barbecue, the color red has been a through line for Juneteenth food for generations. Red symbolizes the bloodshed and sacrifice of enslaved ancestors. A Juneteenth menu might incorporate items like barbecued ribs or other red meat, watermelon and red velvet cake. Drinks like fruit punch and red Kool-Aid may make an appearance at the table.

DOES HOW YOU CELEBRATE JUNETEENTH MATTER IF YOU AREN’T BLACK?

Dr. Karida Brown, a sociology professor at Emory University whose research focuses on race, said there’s no reason to feel awkward about wanting to recognize Juneteenth because you have no personal ties or you’re not Black. In fact, embrace it.

“I would reframe that and challenge my non-Black folks who want to lean into Juneteenth and celebrate,” Brown said. “It absolutely is your history. It absolutely is a part of your experience. ... Isn’t this all of our history? The good, the bad, the ugly, the story of emancipation and freedom for for your Black brothers and sisters under the Constitution of the law.”

If you want to bring some authenticity to your recognition of Juneteenth, educate yourself. Attending a street festival or patronizing a Black-owned business is a good start but it also would be good to “make your mind better,” Anderson said.

“That goes longer than a celebration,” Anderson said. “I think Black people need to do it too because it’s new for us as well, in America. But for non-Black people, if they could read on this topic and read on Black history beyond Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks, that would show me that you’re really serious about growing in this area.”

If you’re struggling with how to “ethically” mark the day, Brown also suggested expanding your knowledge of why the holiday matters so much. That can be through reading, attending an event or going to an African American history museum if there’s one nearby.

“Have that full human experience of seeing yourself in and through the eyes of others, even if that’s not your own lived experience,” she said. “That is a radical human act that is awesome and should be encouraged and celebrated.”

WHAT ARE OTHER NAMES USED TO REFER TO JUNETEENTH?

Over the decades, Juneteenth has also been called Freedom Day, Emancipation Day, Black Fourth of July and second Independence Day among others.

“Because 1776, Fourth of July, where we’re celebrating freedom and liberty and all of that, that did not include my descendants,” Brown said. “Black people in America were still enslaved. So that that holiday always comes with a bittersweet tinge to it.”

IS THERE A PROPER JUNETEENTH GREETING?

It’s typical to wish people a “Happy Juneteenth” or “Happy Teenth,” said Freeman, the comedian.

“You know how at Christmas people will say ‘Merry Christmas’ to each other and not even know each other? You can get a ‘Merry Christmas’ from everybody. This is the same way,” Freeman said.

No matter what race you are, you will “absolutely” elicit a smile if you utter either greeting, he said.

“I believe that a non-Black person who celebrates Juneteenth ... it’s their one time to have a voice, to participate.” (Associated Press).

Black Voters Matter mobilizes the South for Juneteenth bus tour.

Reigniting the spirit of the famous freedom riders, who risked life and limb to register voters across the South during the violent era of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, Black Voters Matter is heading to six states in the South beginning on Friday [June 16].

Cliff Albright, co-founder of Black Voters Matter, talks about expanding voting rights at the John Lewis Advancement Act Day of Action, a voter education and engagement event, Saturday, May 8, 2021, at King’s Canvas in Montgomery, Ala.

Cliff Albright, co-founder of Black Voters Matter, talks about expanding voting rights at the John Lewis Advancement Act Day of Action, a voter education and engagement event, Saturday, May 8, 2021, at King’s Canvas in Montgomery, Ala.

Black Voters Matter, a national organization dedicated to expanding Black voter engagement, is taking its bus tour to the South for Juneteenth, according to an announcement on Friday.

As states like Florida and Texas continue to uphold laws criticized as suppressing the voting power of Black citizens and other people of color, Black Voters Matter (BVM) is taking its We Won’t Back Down tour to the South, with stops in Texas, Florida, Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina between Friday, June 16 and Saturday, June 24.

Partnering with 50 local organizations nationwide, BVM is set to host block parties, documentary film screenings, voter rallies and food pantries during Juneteenth weekend.

“Juneteenth is an opportunity for Black communities to celebrate our progress towards freedom as much as it is a reminder for us to protect what we’ve won, and fight for what’s still owed,” BVM co-founder and executive director Cliff Albright stated.

Following the police lynching of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Black Voters Matter was flooded with donations and became an ecosystem of support for grassroots groups getting out the vote.

According to the Associated Press, BVM was credited with contributing to the turnout in Georgia that resulted in the U.S. Senate-flipping victories of Sens. Raphael Warnock (D-GA) and Jon Ossoff (D-GA), along with Georgia turning blue for Joe Biden in 2020.

The Juneteenth bus tour seeks to build on that momentum and clap-back against laws passed that effectively reduce voter participation.

Laws passed that place restrictions on mail-in voting, the number of accessible polling places and even the ability to distribute water and food to people waiting in line, have all been blasted by civil rights organizations as voter suppression tactics aimed at responding to the increasing power of Black voters.

“We are not free until all of us are free, and right now states are passing racist and discriminatory laws that seek to oppress our communities, and we will not stand for it,” Albright said.

Texas: Friday, June 16 to Monday, June 19, with stops in Fort Worth, Dallas and Galveston.

Florida: Sunday, June 18 to Saturday, June 24, with stops in Gainesville, Ocala, Leesburg, Miami, West Palm Beach and Daytona Beach.

Louisiana: Stops in New Orleans during Juneteenth weekend.

South Carolina: Stops in Mullins on Friday, June 16.

Alabama: Stops in Selma, Tuscaloosa and Carrollton from Saturday, June 17 to Monday, June 19.

Georgia: A statewide bus tour from Friday, June 16 to Monday June 19.

To view the full schedule of events and learn more about the We Won’t Black Down campaign, visit the Black Voters Matter website. (The Black Walls Times).

Rodeo to celebrate the legacy of Black cowboys.

Before there were white cowboys in the American West, there were Latino vaqueros, Indigenous cattle handlers and Black cowboys.

Why it matters: That history, often forgotten in tales of the nation's frontier, is what photographer Ivan McClellan has honored by documenting Black cowboys and cowgirls for nearly a decade — and why he organized a Juneteenth rodeo in Portland, Ore., on Saturday.

McClellan tells Axios he launched the inaugural "Eight Seconds Juneteenth Rodeo" — named for how long a rodeo bull rider has to stay on for a ride to be scored — to provide a venue for Black cowboys and cowgirls to compete in a sport usually dominated by whites.

Black rodeos receive a fraction of sponsorships and winning payouts as big-circuit rodeos. McClellan has attracted sponsors such as Wrangler and Tecovas, allowing the Portland rodeo to offer $60,000 in prize money.

That's more than twice the amount offered at many other Black rodeos — but still well below the hundreds of thousands of dollars offered at bigger rodeos.

The event is drawing cowboys and cowgirls from California, Texas and Oklahoma.

Zoom in: McClellan grew up in Kansas but said that like many Black Americans, he couldn't relate to cowboy culture because of how it was portrayed on TV and in movies.

"What I had seen in film was John Wayne, Montgomery Clift and 'Tombstone' ... all of these white cowboys. The only Black cowboys I'd seen were kind of a joke, like Cowboy Curtis on 'Pee-Wee's Playhouse.' "

That changed when he saw real Black cowboys in Oklahoma and saw similarities with his Kansas family. He began his photo project.

Between the lines: Afro-frontierism has always been part of the American story — even before the arrival of the first enslaved people in Virginia in 1619, historian Timothy E. Nelson tells Axios.

The original American cowboys were Afro-Mexicans in the present-day Southwest, he said.

They later would later meet up with emancipated Black people from the American South, navigated homestead laws — 160 acres of granted federal land to anyone agreeing to farm the land — and threats of land thefts by white settlers.

Yes, but: When the Western genre was created via movies and popular culture, Black cowboys were left out of the picture, said Nelson, author of the upcoming book "Blackdom, New Mexico: The Significance of the Afro-Frontier, 1900–1930."

Showing Black cowboys meant you'd have to discuss the racism they faced and the enslavement they once endured, he said.

"When you see Black people in the context of cowboy-ness, it has nothing to do with white people. In fact, it's a rejection of whiteness."

McClellan said the exclusion of Black cowboys popular Western TV shows and movies is based on "racism and laziness."

The intrigue: Rashad Robinson, president of the activist group Color Of Change, tells Axios the growing popularity of Juneteenth allows Black communities to get behind unique events like rodeos and show different sides of Black history.

"I love that we can take these moments to claim our cultural legacies. Juneteenth is about visibility."

Go deeper: Juneteenth forces U.S. to confront lasting impact of slavery economy. (Axios).

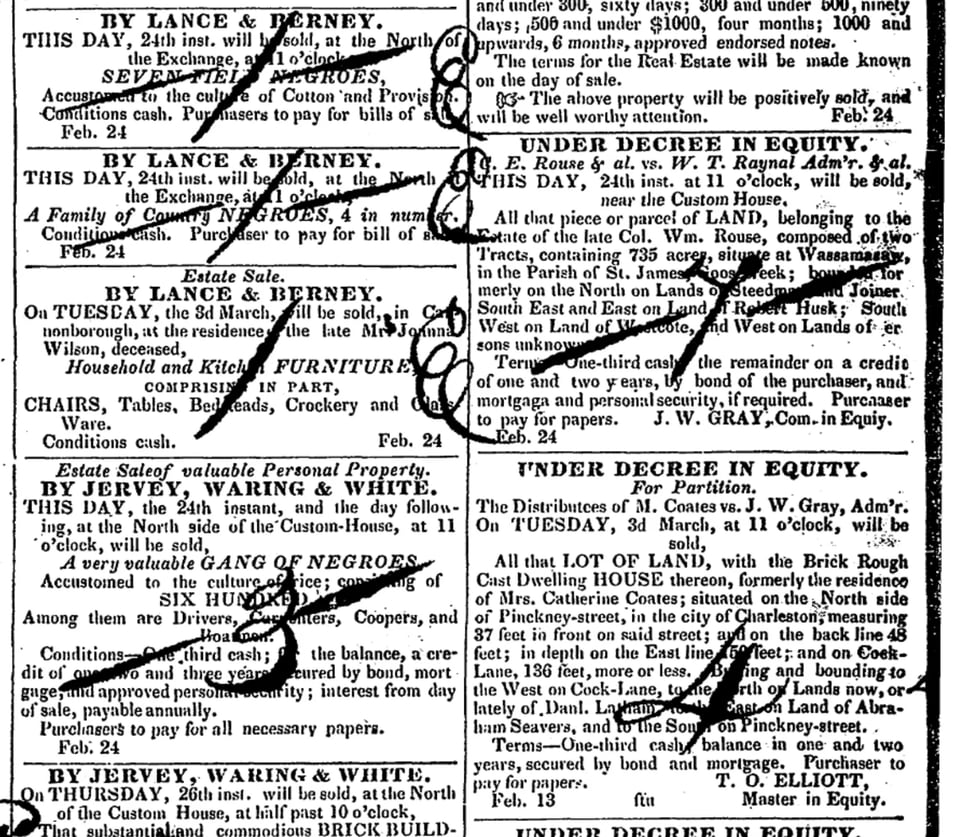

A Grad Student Found the Largest Known Slave Auction in the U.S.

Lauren Davila, then a graduate student at the College of Charleston, found the largest known slave auction while searching archives of classified ads - an ad for a slave auction larger than any historian had yet identified. The find yields a new understanding of the enormous harm of such a transaction.

Sitting at her bedroom desk, nursing a cup of coffee on a quiet Tuesday morning, Lauren Davila scoured digitized old newspapers for slave auction ads. A graduate history student at the College of Charleston, she logged them on a spreadsheet for an internship assignment. It was often tedious work.

She clicked on Feb. 24, 1835, another in a litany of days on which slave trading fueled her home city of Charleston, South Carolina. But on this day, buried in a sea of classified ads for sales of everything from fruit knives and candlesticks to enslaved human beings, Davila made a shocking discovery.

On page 3, fifth column over, 10th advertisement down, she read:

“This day, the 24th instant, and the day following, at the North Side of the Custom-House, at 11 o’clock, will be sold, a very valuable GANG OF NEGROES, accustomed to the culture of rice; consisting of SIX HUNDRED.”

She stared at the number: 600.

A sale of 600 people would mark a grim new record — by far.

Until Davila’s discovery, the largest known slave auction in the U.S. was one that was held over two days in 1859 just outside Savannah, Georgia, roughly 100 miles down the Atlantic coast from Davila’s home. At a racetrack just outside the city, an indebted plantation heir sold hundreds of enslaved people. The horrors of that auction have been chronicled in books and articles, including The New York Times’ 1619 Project and “The Weeping Time: Memory and the Largest Slave Auction in American History.” Davila grabbed her copy of the latter to double-check the number of people auctioned then.

It was 436, far fewer than the 600 in the ad glowing on her computer screen.

She fired off an email to a mentor, Bernard Powers, the city’s premier Black history expert. Now professor emeritus of history at the College of Charleston, he is founding director of its Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston and board member of the International African American Museum, which will open in Charleston on June 27.

If anyone would know about this sale, she figured, it was Powers.

Yet he too was shocked. He had never heard of it. He knew of no newspaper accounts, no letters written about it between the city’s white denizens.

“The silence of the archives is deafening on this,” he said. “What does that silence tell you? It reinforces how routine this was.”

The auction site rests between a busy intersection in downtown Charleston and the harbor that ushered in about 40% of enslaved Africans hauled into the U.S. In that constrained space, Powers imagined the wails of families ripped apart, the smells, the bellow of an auctioneer.

Traffic drives along Broad Street toward the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon in Charleston, the site of slave auctions Davila researched. Public auctions were held outside on the building's north side.

Traffic drives along Broad Street toward the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon in Charleston, the site of slave auctions Davila researched. Public auctions were held outside on the building's north side.

—-

When Davila emailed him, she also copied Margaret Seidler, a white woman whose discovery of slave traders among her own ancestors led her to work with the college’s Center for the Study of Slavery to financially and otherwise support Davila’s research.

The next day, the three met on Zoom, stunned by her discovery.

“There were a lot of long pauses,” Davila recalled.

It was March 2022. She decided to announce the discovery in her upcoming master’s thesis.

A year later, in April, Davila defended that thesis. She got an A.

She had discovered what appears to be the largest known slave auction in the United States and, with it, a new story in the nation’s history of mass enslavement — about who benefited and who was harmed by such an enormous transaction.

But that story initially presented itself mostly as a great mystery.

The ad Davila found was brief. It yielded almost no details beyond the size of the sale and where it was being held — nothing about who sent the 600 people to auction, where they came from or whose lives were about to be uprooted.

But details survived, it turned out, tucked deep within Southern archives.

In May, Davila shared the ad with ProPublica, the first news outlet to reveal her discovery. A reporter then canvassed the Charleston newspapers leading up to the auction — and unearthed the identity of the rice dynasty responsible for the sale.

The Ball Dynasty

The ad Davila discovered ran in the Charleston Courier on the sale’s opening day. But ads for large auctions were often published for several days, even weeks, ahead of time to drum up interest.

A ProPublica reporter found the original ad for the sale, which ran more than two weeks before the one Davila spotted. Published on Feb. 6, 1835, it revealed that the sale of 600 people was part of the estate auction for John Ball Jr., scion of a slave-owning planter regime. Ball had died the previous year, and now five of his plantations were listed for sale — along with the people enslaved on them.

The Ball family might not be a household name outside of South Carolina, but it is widely known within the state thanks to a descendant named Edward Ball who wrote a bestselling book in 1998 that bared the family’s skeletons — and, with them, those of other Southern slave owners.

“Slaves in the Family” drew considerable acclaim outside of Charleston, including a National Book Award. Black readers, North and South, praised it. But as Ball explained, “It was in white society that the book was controversial.” Among some white Southerners, the horrors of slavery had long gone minimized by a Lost Cause narrative of northern aggression and benevolent slave owners.

Based on his family’s records, Edward Ball described his ancestors as wealthy “rice landlords” who operated a “slave dynasty.” He estimated they enslaved about 4,000 people on their properties over 167 years, placing them among the “oldest and longest” plantation operators in the American South.

John Ball Jr. was a Harvard-educated planter who lived in a three-story brick house in downtown Charleston while operating at least five plantations he owned in the vicinity. By the time malaria killed him at age 51, he enslaved nearly 600 people including valuable drivers, carpenters, coopers and boatmen. His plantations spanned nearly 7,000 acres near the Cooper River, which led to Charleston’s bustling wharves and the Atlantic Ocean beyond.

ProPublica reached out to Edward Ball, who lives in Connecticut, to see if he had come across details about the sale during his research.

He said that 25 years ago when he wrote “Slaves in the Family,” he knew an enormous auction followed Ball Jr.’s death, “and yet I don’t think I contemplated it enough in its specific horror.” He saw the sale in the context of many large slave auctions the Balls orchestrated. Only a generation earlier, the estate of Ball Jr.’s father had sold 367 people.

“It is a kind of summit in its cruelty,” Ball said of the auction of 600 humans. “Families were broken apart, and children were sold from their parents, wives sold from their husbands. It breaks my heart to envision it.”

And it gets worse.

After ProPublica discovered the original ad for the 600-person sale, Seidler, the woman who supported Davila’s research, unearthed another puzzle piece. She found an ad to auction a large group of people enslaved by Keating Simons, the late father of Ball Jr.’s wife, Ann. Simons had died three months after Ball Jr., and the ad announced the sale of 170 people from his estate. They would be auctioned the same week, in the same place, as the 600.

That means over the course of four days — a Tuesday through Friday — Ann Ball’s family put up for sale 770 human beings.

In his book, Edward Ball described how Ann Ball “approached plantation management like a soldier, giving lie to the view that only men had the stomach for the violence of the business.” She once whipped an enslaved woman, whose name was given only as Betty, for not laundering towels to her liking, then sent the woman to the Work House, a city-owned jail where Black people were imprisoned and tortured.

A week before the first auction ad appeared for Ball Jr.’s estate, a friend and business adviser dashed off a letter urging Ann Ball to sell all of her late husband’s properties and be freed of the burden. “It is impossible that you could undertake the management of the whole Estate for another year without great anxiety of mind,” the man wrote in a letter preserved at the South Carolina Historical Society.

Ball did what she wanted.

On Feb. 17, the day her husband’s land properties went to auction, she bought back two plantations, Comingtee and Midway — 3,517 acres in all — to run herself.

A week later, on the opening day of the sale of 600 people, she purchased 191 of them.

More Than Names

In mid-March 1835, the auction house ran a final ad regarding John Ball Jr.’s “gang of negroes.” It advertised “residue” from the sale of 600, a group of about 30 people as yet unsold.

Ann Ball bought them as well.

Given she bought most in family groups, her purchase of 215 people in total spared many traumatic separations, at least for the moment.

As she picked who to purchase, she appears to have prioritized long-standing ties. Several were elderly, based on the low purchase price and their listed names — Old Rachel, Old Lucy, Old Charles.

Many names included on her bills of sale also mirror those recorded on an inventory of John Ball Jr.’s plantations, including Comingtee, where he and Ann had sometimes lived. Among them: Humphrey, Hannah, Celia, Charles, Esther, Daniel, Dorcas, Dye, London, Friday, Jewel, Jacob, Daphne, Cuffee, Carolina, Peggy, Violet and many more.

Most of their names are today just that, names.

But Edward Ball was able to find details about at least one family Ann Ball purchased. A woman named Tenah and her older brother Plenty lived on a plantation a few miles downriver from Comingtee that Ball Jr.’s uncle owned.

Edward Ball figured they came from a family of “blacksmiths, carpenters, seamstresses and other trained workers” who lived apart from the field hands who toiled in stifling, muddy rice plots. Tenah lived with her husband, Adonis, and their two children, Scipio and August. Plenty, who was a carpenter, lived next door with his wife and their three children: Nancy, Cato and Little Plenty.

When the uncle died, he left Tenah, Plenty and their children to John Ball Jr. The two families packed up and moved to Comingtee, then home to more than 100 enslaved people.

Life went on. Tenah gave birth to another child, Binah. Adonis tended animals in the plantation’s barnyard.

Although the families were able to stay together, they nonetheless suffered under enslavement. At one point, an overseer wrote in his weekly report to Ball Jr. that he had Adonis and Tenah whipped because he suspected they had butchered a sheep to add to people’s rations, Edward Ball wrote in his book.

After her husband’s death, Ann Ball’s purchase appears to have kept the two families together, at least many of them. The names Tenah, Adonis, Nancy, Binah, Scipio and Plenty are listed on her receipt from the auction’s opening day.

Yet, hundreds more people who remained for sale from the Ball auction likely “ended up in the transnational traffic to Mississippi and Louisiana,” said Edward Ball, now at work on a book about the domestic slave trade.

He noted that buyers attending East Coast auctions were mostly interstate slave traders who transported Black people to New Orleans and the Gulf Coast, then resold them to owners of cotton plantations. In the early 1800s, cotton had taken over from rice and tobacco as the South’s king crop, fueling demand at plantations across the lower South and creating a mass migration of enslaved people.

Birth of Generational Wealth

Although the sale of 600 people as part of one estate auction appears to be the largest in American history, the volume itself is hardly out of place on the vast scale of the nation’s chattel slavery system.

Ethan Kytle, a history professor at California State University, Fresno, noted that the firm auctioning much of Ball’s estate — Jervey, Waring & White — alone advertised sales of 30, 50 or 70 people virtually every day.

“That adds up to 600 pretty quickly,” Kytle said. He and his wife, the historian Blain Roberts, co-wrote “Denmark Vesey’s Garden,” a book that examines what he called the former Confederacy’s “willful amnesia” about slavery, particularly in Charleston, and urges a more honest accounting of it.

Slavery was a form of mass commerce, he said. It made select white families so wealthy and powerful that their surnames still form a sort of social aristocracy in places like Charleston.

Although no evidence has surfaced yet about how much the auction of 600 people enriched the Ball family, the amount Ann Ball paid for about one-third of them is recorded in her bills of sale buried within the boxes and folders of family papers at the South Carolina Historical Society. They show that she doled out $79,855 to purchase 215 people — a sum worth almost $2.8 million today.

The top dollar she paid for a single human was $505. The lowest purchase price was $20, for a person known as Old Peg.

Enslaved people drew widely varied prices depending on age, gender and skills. But assuming other buyers paid something comparable to Ann Ball’s purchase price, an average of $371 per person, the entire auction could have netted in the range of $222,800 — or about $7.7 million today — money then distributed among Ball Jr.’s heirs, including Ann.

They weren’t alone in profiting from this sale. Enslaved people could be bought on credit, so banks that mortgaged the sales made money, too. Firms also insured slaves, for a fee. Newspapers sold slave auction ads. The city of Charleston made money, too, by taxing public auctions. These kinds of profits helped build the foundation of the generational wealth gap that persists even today between Black and white Americans.

Jervey, Waring & White took a cut of the sale as well, enriching the partners’ bank accounts and their social standing.

Although the men orchestrated auctions to sell thousands of enslaved people, James Jervey is remembered as a prominent attorney and bank president who served on his church vestry, a “generous lover of virtue,” as the South Carolina Society described him in an 1845 resolution. A brick mansion in downtown Charleston bears his name.

Morton Waring married the daughter of a former governor. Waring’s family used enslaved laborers to build a three-and-a-half story house that still stands in the middle of downtown. In 2018, country music star Darius Rucker and entrepreneur John McGrath bought it from the local Catholic diocese for $6.25 million.

Alonzo J. White was among the most notorious slave traders in Charleston history. He also served as chairman of the Work House commissioners, a role that required him to report to the city fees garnered from housing and “correction” of enslaved people tortured in the jail.

“Yet, these men were upheld by high society,” Davila said. “They are remembered as these great Christian men of high value.” After John Ball Jr. died, the City Council passed a resolution to express “a high testimonial of respect and esteem for his private worth and public services.”

But for the 600 people sold and their descendants? Only a stark reminder of how America’s entrenched racial wealth gap was born, Davila said, with repercussions still felt today. (ProPublica).

_________________________