Monday, July 31, 2023. Annette’s News Roundup.

I think the Roundup makes people feel not so alone.

To read an article excerpted in this Roundup, click on its blue title. Each “blue” article is hyperlinked so you can read the whole article.

Please feel free to share.

Invite at least one other person to subscribe today! buttondown.email/AnnettesNewsRoundup

_________________________

Joe is always busy.

Senator Kirsten Gillibrand fought for years to protect military women. The President recognized this.

.@JoeBiden left me a message right before he signed an executive order finalizing reforms to the military justice system that started with a bill I fought nearly a decade to pass.

— Kirsten Gillibrand (@SenGillibrand) July 29, 2023

Service members will finally have a fair, impartial, professional justice system. And I’m so… pic.twitter.com/6Nv7U6DyQE

Click the tweet below to hear the President say this.👇

“Kirsten, Joe Biden in the Oval Office. I wish you were here because I am about to sign a bill that you are totally responsible for, which the New York Times says is the biggest change in modern military system since 1950. You deserve all the credit, all the credit. I just called to say Congratulations. Looking forward to seeing you.”

Https://twitter.com/SenGillibrand/status/1685310752217821184/video/1

_________________________

One important poll shows Trump losing support.

Trump’s numbers fell even before the newest obstruction charges from Mar-a-Largo.

GOP support for Trump softens as the former president's legal troubles mount.

The pile-on effect of mounting legal charges against former President Trump may be starting to take a toll, according to the latest NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll.

Republicans and Republican-leaning independents saying they believe Trump has done "nothing wrong" dropped 9 points in the last month, from 50% to 41%.

Trump also dropped 6 points in support with that same group when asked whether they were more likely to support Trump or another candidate, if he continues to run for president.

Still, a solid majority — 58% — continue to say they would support Trump as their standard-bearer, so more polling and time would be necessary to see if this is a trend, if it continues and if it has a real effect on his chances in the GOP primary. He continues to lead the field by wide margins.

At the same time, though, Trump has become increasingly toxic with the political middle, and this survey bears that out. A slim majority — 51% — of respondents overall said they think Trump did something illegal, including 52% of independents.

The findings come as Trump is likely set to face yet another indictment, his third, for his role in the Jan. 6 insurrection, and potentially a fourth in a Georgia election interference case.

The survey of 1,285 adults, including 455 Republicans was conducted from Monday through Thursday. When all adults are noted, there is a +/- 3.6 percentage point margin of error, meaning the results could range from about 4 points lower to 4 points higher. When Republicans and Republican-leaning independents are noted, there is a higher +/- 6.1 percentage point margin of error.

The poll was conducted before the latest news Thursday afternoon of Trump facing an additional charge in the federal classified documents case against him.

This is nothing more than a continued desperate and flailing attempt by the Biden Crime Family and their Department of Justice to harass President Trump and those around him.

Trump responds as the base looks on

Trump has responded to the looming indictment and the additional charge of willful retention of National Defense Information he's now facing by blasting the Justice Department and the Biden administration and claiming to be targeted because of politics.

"This is nothing more than a continued desperate and flailing attempt by the Biden Crime Family and their Department of Justice to harass President Trump and those around him," the Trump campaign said in a written statement of the new charge.

In an interview with the conservative web site Breitbart, Trump claimed "harassment" and "election interference" on the part of the government.

"They did this to try and get me out," he said, also claiming, "It's lifted my numbers."

But the results of this survey show that's not completely true. Just as Trump's ironclad grip last year seemed to be loosening, the search at his Florida home did lift his numbers with Republicans.

The search helped to solidify him with a significant swath of the base, which believes Trump's assertions that he's the victim of political persecution. But some Republicans are nowarguing that Trump is not electable and brings too much baggage.

Many of Trump's top GOP primary opponents have not made a public case against Trump relating to his legal woes. Two political action committees, however, have begun to run millions of dollars worth of ads in early states taking direct aim at Trump's "baggage" and "drama." (NPR).

One more thing -

I posted this yesterday but again, here is Trump arriving on stage at a rally in Iowa as a song lyric 'going to prison' plays. Feel free to watch again, so you can smile.👇

_________________________

The Baker Boy “did good.” How much privilege and access and money does it take?

Who has the confidence to do work like this? What 17 year old has the funds to “engage” scientists to test your theories?

2 articles about the journalist Peter Baker’s son, Theo Baker, who brought the President of Stanford down.

Meet the student who helped boot the president of Stanford.

Theo Baker with his Polk Prize. Courtesy of Theo Baker.

Theo Baker with his Polk Prize. Courtesy of Theo Baker.

SAN FRANCISCO — On Christmas Day, Theo Baker was pacing around a relative’s home in Los Angeles, mumbling to himself: “How am I going to get inside Genentech? How am I going to get inside Genentech? How am I going to get inside Genentech?”

He was a freshman at Stanford University, just a few months into his career as a college journalist, and already fixated on a huge reporting challenge: Finding workers at a Bay Area biotech company, where Stanford’s president had once been a top executive, to scrutinize research he’d overseen. Baker’s parents were initially concerned and skeptical when he told them about pursuing allegations of research misconduct that could implicate Marc Tessier-Lavigne, a neuroscientist who had just completed his sixth year as the head of Stanford.

“Be careful here,” Peter Baker recalls telling his son. “This guy is a world-renowned scientist, and you’re a 17-year-old kid.”

As journalists, Theo Baker’s parents have covered wars and presidents. His mother, Susan Glasser, is a former Washington Post editor who’s now a staff writer at the New Yorker. Peter Baker, a former Post reporter, is the chief White House correspondent for the New York Times. Theo Baker’s investigation would soon win him a special George Polk Award. Not only did his reporting for the Stanford Daily get inside Genentech, it also contributed to Tessier-Lavigne’s resignation this month.

How did it all happen? Through a helpful tip from a friend, a dogged but careful reporting process, and a childhood — surrounded by his parents’ endeavors in journalism — that prepared him for the pace and heat of a big story.

Growing up with two notable bylines as parents, Baker learned through example and osmosis. Before he could read or type, Baker was toddling around the Washington Post newsroom. Some of his fondest memories, he says, are of workshopping unpublished headlines with his mother when he was 7 or 8.

“My parents have always included me, even when they had no obligation to,” Baker said. He’s had firsthand lessons in the demands of the 24/7 news cycle. Baker has seen his parents cut short vacations and dinners because of breaking news. On multiple occasions he’s nearly walked on camera, pajama-clad, as they’ve been in the middle of television hits at home. Now he’s doing TV interviews himself.

“He had the velocity of the news cycle ingrained in him from an early age,” Glasser said of her son. As a middle schooler during the Trump administration, Baker had multiple news alerts set up on his phone and would often text his parents during the school day, inquiring about the implications of the president’s latest announcement or executive order.

Baker chose Stanford because it was a place he could pursue an array of interests, from humanities to the ethics of artificial intelligence. He’s hosted campus hackathons and has embedded with a student group of amateur race-car drivers. Frank Zhou, Baker’s best friend from boarding school at Phillips Academy Andover, recalls intense ping-pong matches — Baker has a tell-tale tennis stroke, Zhou says — and late-night dorm hallway conversations about German literature.

Last fall, one of Baker’s friends, a recent Stanford graduate, directed him to a post on PubPeer — a website where scientists raise questions about published research — that pointed out aberrations in reports fromTessier-Lavigne’s research team.

In early October, Baker engaged scientific experts to review the papers co-authored by Tessier-Lavigne that contained images alleged by experts to be manipulated. Baker’s reporting enlisted multiple scientific experts to examine, corroborate and ultimately expand upon the concerns raised on PubPeer.

On Nov. 30, the day after the Daily published the first of more than a dozen stories about the allegations, the university convened a panel of experts to independently examine Tessier-Lavigne’s research. Last week that panel found that Tessier-Lavigne had failed to correct errors in years-old scientific papers and had overseen labs with an “unusual frequency” of data manipulations. On July 19 Tessier-Lavigne announced in a statement that he’d step down as university president Aug. 31 but remain on the Stanford faculty. Tessier-Lavigne also said that he would ask for three papers to be retracted and two corrected.

The report from the panel “clearly refutes the allegations of fraud and misconduct that were made against me” online, Tessier-Lavigne wrote, adding that “in some instances I should have been more diligent when seeking corrections, and I regret that I was not. The Panel’s review also identified instances of manipulation of research data by others in my lab. Although I was unaware of these issues, I want to be clear that I take responsibility for the work of my lab members.”

In February, at 18 years old, Baker won the special Polk award for his reporting in the Daily. He’s the youngest person to ever win a Polk, though it’s not unusual for college journalists to have a profound impact on their universities. This month, Northwestern University fired its football coach after the Daily Northwestern reported on specific details of hazing that had led to the coach’s suspension.

Sam Catania, the Daily’s editor in chief for the past academic year, said his role was to be the skeptic, constantly asking questions of Baker’s reporting and prodding him to consider whether his sources might have ulterior motives. “We tried to never be overconfident,” Catania said in an interview.

Oriana Riley, a rising junior and editor at the Daily, observed Baker working so many late nights that she would unsuccessfully urge him to get some sleep to avoid burning out. “A lot of people at Stanford have this trait,” Riley said. “Sometimes they will not give up on things to the point where maybe you should give up — or at least take a break.”

Baker and his parents insist that he and his peers did this work without the parents getting involved. The student journalists had the benefit of pre-publication consultations and edits from the Daily’s professional advisers — one of whom is a current Washington Post editor who also serves on the Daily’s board of directors — and a pro-bono legal review from the law firm Davis Wright Tremaine.

“My parents — they don’t read my copy before it goes out,” Baker notes, adding: “They’re not my editors.”

One way Baker’s parents have had a distinct influence on him is in hammering home the importance of attending classes even while you’re plugging away on an important story. Peter Baker dropped out of Oberlin College after two years to pursue a career in journalism — something his son doesn’t plan to emulate.

“He’s doing what his father never did — he’s going to classes,” Peter said in an interview. (The younger Baker concedes that he did skip a lecture on Machiavelli to break a story about Tessier-Lavigne.)

Former Post editor R.B. Brenner, a Stanford journalism lecturer who recently left the Daily’s advisory board, said that Baker brought to Stanford a “Washington sophistication” in his understanding of stories that “require a fair number of anonymous sources and there can be quite a level of risk involved.”

It was isolating for a campus newbie to be investigating the university president. Baker said he had a “great, fantastic team” at the Daily, but other outlets weren’t pushing this story forward. “I was really scared, and I felt really alone,” Baker said of the experience.

Sometimes, fellow students would treat him “like a zoo animal,” he said, by walking past his dorm room and pointing out that Baker was the student journalist investigating the president. “I just started at Stanford and I was still trying to find my friends,” Baker said. “It was a little weird when people would interrupt in the middle of class and be like, ‘Oh my god, you’re that kid!’ or come up to me when I’m trying to go to a party.” He gave up on Tinder after one week of swiping, he said, because so many matches commented about his journalism or suggested new reporting targets.

Baker is currently working in Berlin for the summer with the Anti-Corruption Foundation, Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s organization, to track down companies evading sanctions to provide Russia with materiel for its war against Ukraine.

Baker, a rising sophomore, has yet to choose a major. “I will probably end up doing some mix of humanities and STEM technology stuff,” he said. (The Washington Post).

From Theo Baker himself - “The NYT asked me to write a guest essay about the resignation of Stanford's president. My takeaway? This is so much bigger than one man and his research. Scientific integrity is vital and its guardrails have proven insufficient:”

The Research Scandal at Stanford Is More Common Than You Think.

There are many rabbit holes on the internet not worth going down. But a comment on an online science forum called PubPeerconvinced me something might be at the bottom of this one. “This highly cited Science paper is riddled with problematic blot images,” it said. That anonymous 2015 observation helped spark a chain of events that led Stanford’s president, Marc Tessier-Lavigne, to announce his resignation this month.

Dr. Tessier-Lavigne made the announcement after a university investigation found that as a neuroscientist and biotechnology executive, he had fostered an environment that led to “unusual frequency of manipulation of research data and/or substandard scientific practices” across labs at multiple institutions. Stanford opened the investigation in response to reporting I published last autumn in The Stanford Daily, taking a closer look at scientific papers he published from 1999 to 2012.

The review focused on five major papers for which he was listed as a principal author, finding evidence of manipulation of research data in four of them and a lack of scientific rigor in the fifth, a famous study that he said would “turn our current understanding of Alzheimer’s on its head.” The investigation’s conclusions did not line up with my reporting on some key points, which may, in part, reflect the fact that several people with knowledge of the case would not participate in the university’s investigation because it declined to guarantee them anonymity. It did confirm issues in every one of the papers I reported on. (My team of editors, advisers and lawyers at The Stanford Daily stand by our work.)

In retrospect, much of the data manipulation is obvious. Although the report concluded that Dr. Tessier-Lavigne was unaware at the time of the manipulation that occurred in his labs, in papers on which he served as a principal author, images had been improperly copied and pasted or spliced; results had been duplicated and passed off as separate experiments; and in some instances — in which the report found an intention to hide the manipulation — panels had been stretched, flipped and doctored in ways that altered the published experimental data. All of this happened before he became Stanford’s president. Why, then, didn’t it come out sooner?

The answer is that people weren’t looking.

This year, a panel of scientists began reviewing the allegations against Marc Tessier-Lavigne, focusing on five papers for which he was a principal author.

In the earliest paper reviewed, a 1999 study about neural development, the panel found that an image from one experiment had been flipped, stretched and then presented as the result of a different experiment.

A 2004 paper contained similar manipulations, including an image that was reused to represent different experiments.

“Basic biostatistical computational errors” and “image anomalies” were found in a 2009 paper about Alzheimer’s that has been cited over 800 times, including the reuse of a control image with improper labeling.

At least four of the five papers appear to have manipulated data. Dr. Tessier-Lavigne has stated that he intends to retract three of the papers and correct the other two.

The report and its consequences are an unhappy outcome for a powerful, influential, wealthy scientist described by a colleague in a 2004 Nature Medicine profile as essentially “being perfect.” The first in his family to go to college, Dr. Tessier-Lavigne earned a Rhodes scholarship before establishing a lab at the University of California, San Francisco, in the 1990s and discovering netrins, the proteins responsible for guiding axon growth. “He’s one of those people for whom things always seemed to go just right,” an acquaintance recalled in the Nature Medicine article.

Anonymous sleuths had raised concerns of alteration in some of the papers on PubPeer, a web forum for discussing published scientific research, since at least 2015. These public questions remained hidden in plain sight even as Dr. Tessier-Lavigne was being vetted for the presidency of Stanford, an institution with a budget of $8.9 billion for next year — larger than that of the entire state of Iowa. Reporters did not pick up on the allegations, and journals did not correct the scientific record. Questions that should have been asked, weren’t.

Peer review, a process designed to ensure the quality of studies before publication, is based on a foundation of honesty between author and reviewer; that process has often failed to catch brazen image manipulation. And when concerns are raised after the fact, as they were in this case, they often fail to gain public attention or prompt correction of the scientific record.

This is a major issue, one that extends well beyond one man and his career. Absent public scrutiny, journals have been consistently slow to act on allegations of research falsification. In a field dependent on good faith cooperation, in which each contribution necessarily builds on the science that came before it, the consequences can compound for years.

When we first went to Dr. Tessier-Lavigne with questions in the fall, a Stanford spokeswoman responded instead, claiming the concerns raised about three of his publications “do not affect the data, results or interpretation of the papers.” But as the Stanford-sponsored investigation found and he eventually came to agree, that was not true.

Dr. Tessier-Lavigne’s plan to retract or issue robust corrections for at least five papers for which he was a principal author is a rare act for a scientist of his stature. It seems unlikely this would have happened without the public pressure of the past eight months; in fact, the report concluded that “at various times when concerns with Dr. Tessier-Lavigne’s papers emerged — in 2001, the early 2010s, 2015-16 and March 2021 — Dr. Tessier-Lavigne failed to decisively and forthrightly correct mistakes in the scientific record.”

The Stanford investigation did not find that Dr. Tessier-Lavigne personally altered data or pasted pieces of experimental images together. Instead, it found that he had presided over a lab culture that “tended to reward the ‘winners’ (that is, postdocs who could generate favorable results) and marginalize or diminish the ‘losers’ (that is, postdocs who were unable or struggled to generate such data).” In a statement, Dr. Tessier-Lavigne said, “I can state categorically that I did not desire this dynamic. I have always treated all the scientists in my lab with the utmost respect, and I have endeavored to ensure that all members flourish as successful scientists.”

Winner-takes-all stakes are, unfortunately, an all-too-common occurrence in academic science, with postdoctoral researchers often subject to the intense pressure of the need to publish or perish. Having a paper with your name on it in Nature, Science or Cell, the high-profile journals in which many of the papers reviewed by the Stanford investigation appeared, can make or break young careers. Postdocs are underpaid; Stanford recently purchased housing that was intended to be affordable for them, then reportedly set minimum salary requirements for living there higher than their wages. They are also jockeying to stand out in a field with limited lab positions and professorship openings. And senior researchers sometimes take credit for their postdocs’ work and ideas but brush off responsibility should errors or mistakes arise.

What isn’t common, of course, is the “frequency of manipulation of research data and/or substandard scientific practices” in the labs Dr. Tessier-Lavigne ran, the Stanford report concluded. Falsification, the technical term for much of this conduct, involves “violating fundamental research standards and basic societal values,” according to the National Academy of Sciences. In his statement, Dr. Tessier-Lavigne said that he has “always sought to model the highest values of the profession, both in terms of rigor and of integrity, and I have worked diligently to promote a positive culture in my lab.” Despite the report’s characterization of what went on in his labs as rare and irregular, lessons from this case apply across the field, especially regarding the importance of correcting the scientific record.

A 2016 study by a handful of prominent research misconduct investigators — including the well-known image analyst and microbiologist Elisabeth Bik, who helped identify a number of the manipulations in the work coming out of Dr. Tessier-Lavigne’s labs — showed that around 3.8 percent of published studies include “problematic figures,” with at least half of those showing signs of “deliberate manipulation.” But only approximately 0.04 percent of published studies are retracted. That gap, which shows a lack of accountability among both individual researchers and the scientific journals, is a profoundly unfortunate sign of a culture in which admitting failures has been stigmatized, rather than encouraged.

“My lab management style has been centered on trust in my trainees,” Dr. Tessier-Lavigne said in his statement. “I have always looked at their science very critically, for example to ensure that experiments are properly controlled and conclusions are properly drawn. But I also have trusted that the data they present to me are real and accurate,” he wrote.

Science is a team sport, but as the report concluded, Dr. Tessier-Lavigne, a principal author with final authority over the data, was responsible for addressing the issues in his research when they were brought to his attention. In the judgment of the Stanford investigation, he “could not provide an adequate explanation” for why he had not done so.

To his credit, he began the correction process for a few of these examples of data manipulation in 2015, when the first allegations were made publicly. But when Science failed to publish the corrections for two of those papers, the report found that after “a final inquiry on June 22, 2016, Dr. Tessier-Lavigne ceased to follow up.” He was made aware of the allegations once more when public discussion resumed in 2021. The report found that he drafted an email inquiring about the unpublished corrections but did not send it. He will now retract both those papers.

In another case — in which there was no public pressure to act — he was made aware “within weeks” of an error in a 2001 paper, according to the Stanford report. Although he wrote to a colleague that he would correct the scientific record, “he did not contact the journal, and he did not attempt to issue an erratum, which is inadequate,” the report concluded.

In the past few years, the field has made great strides to combat image manipulation, including the use of resources like PubPeer, better software detection tools and the prevalence of preprints that allow research to be discussed before it is published. Sites like Retraction Watch have also furthered awareness of the problem of research misconduct. But clearly, there is still progress to be made.

The shake-up at Stanford has already prompted conversations across the scientific community about its ramifications. Holden Thorp, the editor in chief of Science, concluded that the “Tessier-Lavigne matter shows why running a lab is a full-time job,” questioning the ability of researchers to ensure a rigorous research environment while taking on increasing outside responsibilities. An article in Nature examined “what the Stanford president’s resignation can teach lab leaders,” concluding that the case was “reinvigorating conversations about lab culture and the responsibilities of senior investigators.”

This self-reflection in the scientific research community is important. To address research misconduct, it must first be brought into the light and examined in the open. The underlying reasons scientists might feel tempted to cheat must be thoroughly understood. Journals, scientists, academic institutions and the reporters who write about them have been too slow to open these difficult conversations.

Seeking the truth is a shared obligation. It is incumbent on all those involved in the scientific method to focus more vigorously on challenging and reproducing findings and ensuring that substantiated allegations of data manipulation are not ignored or forgotten — whether you’re a part-time research assistant or the president of an elite university. In a cultural moment when science needs all the credibility it can muster, ensuring scientific integrity and earning public trust should be the highest priority.

Theo Baker is a rising sophomore at Stanford University. He is the son of Peter Baker, the chief White House correspondent for The Times. (New York Times).

_________________________

A Serious Discussion of a Congressman and the N.R.A.

One reason we are where we are.

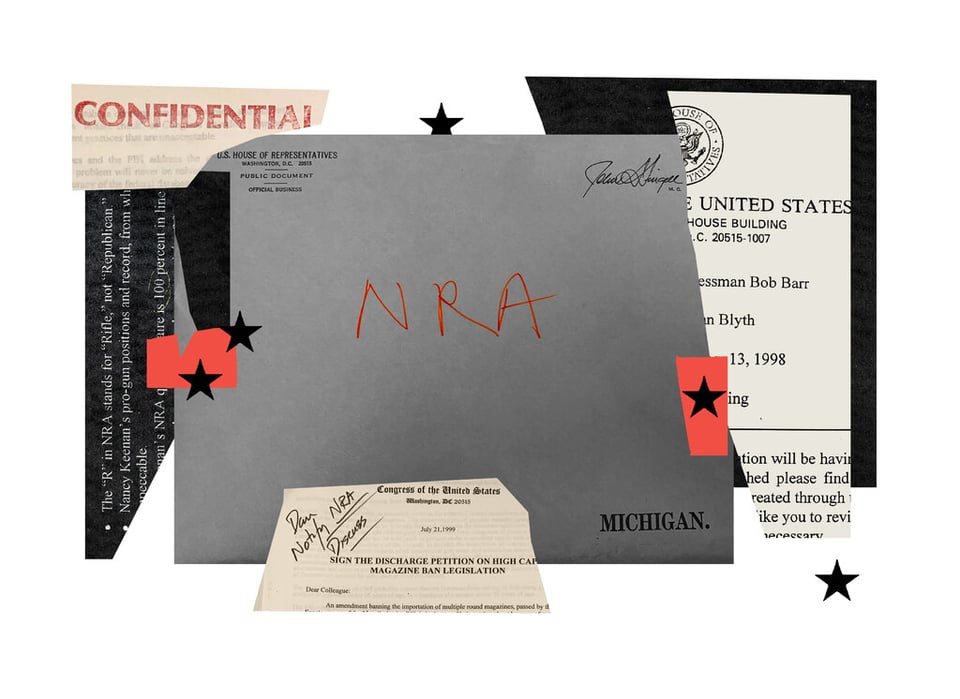

The Secret History of Gun Rights: How Lawmakers Armed the N.R.A.

They served in Congress and on the N.R.A.’s board at the same time. Over decades, a small group of legislators led by a prominent Democrat pushed the gun lobby to help transform the law, the courts and views on the Second Amendment.

Long before the National Rifle Association tightened its grip on Congress, won over the Supreme Court and prescribed more guns as a solution to gun violence — before all that, Representative John D. Dingell Jr. had a plan.

First jotted on a yellow legal pad in 1975, it would transform the N.R.A. from a fusty club of sportsmen into a lobbying juggernaut that would enforce elected officials’ allegiance, derail legislation behind the scenes, redefine the legal landscape and deploy “all available resources at every level to influence the decision making process.”

“An organization with as many members, and as many potential resources, both financial and influential within its ranks, should not have to go 2d or 3d Class in a fight for survival,” Mr. Dingell wrote, advocating a new aggressive strategy. “It should go First Class.”

To understand the ascendancy of gun culture in America, the files of Mr. Dingell, a powerful Michigan Democrat who died in 2019, are a good place to start. That is because he was not just a politician — he simultaneously sat on the N.R.A.’s board of directors, positioning him to influence firearms policy as well as the private lobbying force responsible for shaping it.

And he was not alone. Mr. Dingell was one of at least nine senators and representatives, both Republicans and Democrats, with the same dual role over the last half-century — lawmaker-directors who helped the N.R.A. accumulate and exercise unrivaled power.

Their actions are documented in thousands of pages of records obtained by The New York Times, through a search of lawmakers’ official archives, the papers of other N.R.A. directors and court cases. The files, many of them only recently made public, reveal a secret history of how the nation got to where it is now.

Over decades, politics, money and ideology altered gun culture, reframed the Second Amendment to embrace ever broader gun rights and opened the door to relentless marketing driven by fear rather than sport. With more than 400 million firearms in civilian hands today and mass shootings now routine, Americans are bitterly divided over what the right to bear arms should mean.

The lawmakers, far from the stereotype of pliable politicians meekly accepting talking points from lobbyists, served as leaders of the N.R.A., often prodding it to action. At seemingly every hint of a legislative threat, they stepped up, the documents show, helping erect a firewall that impedes gun control today.

“Talk about being strategic people in a place to make things happen,” an N.R.A. executive gushed at a board meeting after Congress voted down gun restrictions following the 1999 Columbine shooting. “Thank you. Thank you.”

The fact that some members of Congress served on the N.R.A. board is not new. But much of what they did for the gun group, and how, was not publicly known.

Representative Bob Barr, a Georgia Republican, sent confidential memos to the N.R.A. leader Wayne LaPierre, urging action against gun violence lawsuits. Senator Ted Stevens, an Alaska Republican, chided fellow board members for failing to advance a bill that rolled back gun restrictions, and told them how to do it.

Republican Representative John M. Ashbrook of Ohio co-wrote a letter to the board describing “very subtle and complex” tactics to support “candidates friendly to our cause and actions to defeat or discipline those who are hostile.” Senator Larry E. Craig, an Idaho Republican who was a key strategic partner for the N.R.A., flagged and scuttled a proposal to require the use of gun safety locks.

Representative Bob Barr, a Georgia Republican, wrote to the N.R.A. leader Wayne LaPierre in 1999 urging action against gun violence lawsuits. It was one of several memos raising alarms about firearms issues in Congress.

Representative Bob Barr, a Georgia Republican, wrote to the N.R.A. leader Wayne LaPierre in 1999 urging action against gun violence lawsuits. It was one of several memos raising alarms about firearms issues in Congress.

And then there was Mr. Dingell. In a private letter in October 1978, the N.R.A. president, Lloyd Mustin, said his “insights and guidance on the details of any gun-related matter pending in the Congress” were “uniformly successful.” Just as valuable, he said, was the congressman’s stealthy manipulation of the legislative process.

“These actions by him are often carefully obscured,” Mr. Mustin wrote, so they may “not be recognized or understood by the uninitiated observer.”

As chairman of the powerful House commerce committee, Mr. Dingell would send “Dingellgrams” — demands for information from federal agencies — drafted by the N.R.A. Other times, on learning of a lawmaker’s plan to introduce a bill, he would scribble a note to an aide saying, “Notify N.R.A.”

Beginning in the 1970s, he pushed the group to fund legal work that could help win court cases and enshrine policy protections. The impact would be far-reaching: Some of the earliest N.R.A.-backed scholars were later cited in the Supreme Court’s District of Columbia vs. Heller decision affirming an individual right to own a gun, as well as a ruling last year that established a new legal test invalidating many restrictions.

The files of Mr. Dingell, the longest-serving member of Congress, were donated to the University of Michigan but remained off-limits for nearly eight years. They were only made available in May, five months after The Times began pressing for their release.

Mr. Barr, who has remained on the N.R.A. board since leaving government in 2003, said in an interview that he did not recall the memos he wrote to Mr. LaPierre, which were among the congressman’s papers at the University of West Georgia. But during his nearly six years in office while also a N.R.A. director, he said, the group “never approached me to do anything that I didn’t want to do or that I would not have done anyway.”

“I’m doing it as a member of Congress who also happens to be an N.R.A. board member,” Mr. Barr said.

N.R.A. manuals say its board has a “special trust” to ensure the organization’s success and to protect the Second Amendment “in the legislative and political arenas.” Under ethics rules, lawmakers may serve as unpaid directors of nonprofits, and the gun group is classified by the I.R.S. as a nonprofit “social welfare organization.” No current legislators serve on its board.

In 2004, the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence objected to three Republican lawmakers then serving as unpaid N.R.A. directors: Mr. Craig and Representatives Don Young of Alaska and Barbara Cubin of Wyoming. The Brady organization argued that their fiduciary duty to the N.R.A. conflicted with their government roles.

“Here, the lobbyist and the lobbied are the same,” said the complaint. It was rejected by Senate and House ethics committees.

Mr. Dingell eventually left the N.R.A. board. The turning point was his support for a 1994 crime bill that included an assault weapons ban. In a terse resignation letter, he acknowledged a problem in serving as an elected official and a director — though he would continue to work closely with the group for years.

“I deeply regret,” Mr. Dingell wrote, “that the conflict between my responsibilities as a Member of Congress and my duties as a board member of the National Rifle Association is irreconcilable.”

Mr. Dingell, left, being sworn in by House Speaker Sam Rayburn in 1955. He would go on to be the longest-serving member of Congress.

Mr. Dingell, left, being sworn in by House Speaker Sam Rayburn in 1955. He would go on to be the longest-serving member of Congress.

‘Patriotic Duty’

John Dingell was comfortable with firearms at an early age: When not blasting ducks with a shotgun, he was plinking rats with an air gun in the basement of the U.S. Capitol, where he served as a page. They were pursuits he picked up from his father, a New Deal Democrat representing a House district in Detroit’s working-class suburbs, who enjoyed hunting and championed conservation causes.

After serving in the Army in World War II, the younger Mr. Dingell earned a law degree and worked as a prosecutor. He succeeded his father in 1955 at age 29. Nicknamed “the Truck” as much for his forceful personality as his 6-foot-3 frame, Mr. Dingell was an imposing presence in the House, where he became a Democratic Party favorite for pushing liberal causes like national health insurance.

Mr. Dingell recalled, in a 2016 interview, that he saw President John F. Kennedy “fairly frequently” at the White House and generally “traveled the same philosophical path.”

“Except on firearms,” he added.

In December 1963, just weeks after Mr. Kennedy was murdered with a rifle bought through an N.R.A. magazine ad, Mr. Dingell complained at a hearing about “a growing prejudice against firearms” and defended buying guns through the mail. His advocacy made him popular with the N.R.A., and by 1968 he had joined at least one other member of Congress on its board.

Historically, the N.R.A.’s opposition to firearms laws was tempered. Founded in 1871 by two Union Army veterans — a lawyer and a former New York Times correspondent — the association promoted rifle training and marksmanship. It did not actively challenge the Supreme Court’s view, stated in 1939, that the Second Amendment’s protection of gun ownership applied to membership in a “well regulated Militia” rather than an individual right unconnected to the common defense.

During the 1960s, public outrage over political assassinations and street violence led to calls for stronger laws, culminating in the Gun Control Act, the most significant firearms bill since the 1930s. The law would restrict interstate sales, require serial numbers on firearms and make addiction or mental illness potential disqualifiers for ownership. The N.R.A. was divided, with a top official complaining about parts of the bill while also saying it was something “the sportsmen of America can live with.”

President Lyndon B. Johnson wanted the bill to be even stronger, requiring gun registration and licensing, and angrily blamed an N.R.A. letter-writing campaign for weakening it. The Justice Department briefly investigated whether the group had lobbied without registering, and in F.B.I. interviews, N.R.A. officials “pointed out” that members of Congress sat on its board, as if that defused any lobbying concerns. (The case was closed when the N.R.A. agreed to register.)

The debate over the Gun Control Act agitated Mr. Dingell, his files show. He asked the Library of Congress to research Nazi-era gun confiscations in Germany to help prove that regulating firearms was a slippery slope. He considered investigating NBC News for a gun rights segment he viewed as one-sided. At an N.R.A. meeting, he railed about a “patriotic duty” to oppose the “ultimate disarming of the law-abiding citizen.”

Mr. Dingell wrote to a constituent explaining his dual role as a member of Congress and an N.R.A. director.

Mr. Dingell wrote to a constituent explaining his dual role as a member of Congress and an N.R.A. director.

As Mr. Johnson prepared to sign the act in fall 1968, Mr. Dingell was convinced that gun ownership faced an existential threat and wrote to an N.R.A. executive suggesting a bold strategy.

The group, he said, must “begin moving toward a legislative program” to codify an individual’s right to bear arms “for sporting and defense purposes.” It was a major departure from the Supreme Court’s sparse record on Second Amendment issues up to that point. The move would neutralize arguments for tighter gun restrictions in Congress and all 50 states, he said.

“By being bottomed on the federal constitutional right to bear arms,” he wrote, “these same minimal requirements must be imposed upon state statutes and local ordinances.”

A New Aggressiveness

Mr. Dingell’s legislative acumen proved indispensable to the gun lobby.

The 1972 Consumer Products Safety Act, designed to protect Americans from defective products, might have reduced firearms accidents that killed or injured thousands each year. But the N.R.A. viewed it as a backdoor to gun control, and Mr. Dingell slipped in an amendment to the new law, exempting from regulatory oversight items taxed under “section 4181 of the Internal Revenue Code” — which only covers firearms and ammunition.

While Mr. Dingell’s office was publicly boasting in 1974 of his bill to restrict “Saturday night specials,” cheap handguns often used in crimes, C.R. Gutermuth, then the N.R.A.’s president, confided in a private letter that the congressman had only introduced it to “effectively prevent” stronger bills. “Obviously, this comes under the heading of legislative maneuvering and strategy,” he wrote.

Still, the public generally favored stricter limits. After a 3-year-old Baltimore boy accidentally killed a 7-year-old friend with an unsecured handgun, a constituent wrote to Mr. Dingell asking, “How long is it going to be before Congress takes effective action?” He instructed an aide to “not answer.”

Creating a more aggressive lobbying operation was on Mr. Dingell’s mind as he jotted notes ahead of an N.R.A. board meeting in 1975.

Creating a more aggressive lobbying operation was on Mr. Dingell’s mind as he jotted notes ahead of an N.R.A. board meeting in 1975.

When the N.R.A. board met in March 1974, Mr. Gutermuth reported that “Congressman Dingell and some of our other good friends on The Hill keep telling us that we soon will have another rugged firearms battle on our hands.” Yet he expressed dismay that N.R.A. staff had not come up with a “concrete proposal” to fend it off.

Mr. Dingell had an idea.

In memos to the board, he complained of the N.R.A.’s “leisurely response to the legislative threat” and proposed a new lobbying operation. Handwritten notes reflect just how radical his plans were. He initially said the group, which traditionally stayed out of political races, would “not endorse candidates for public office” — only to cross that out with his pen; the N.R.A. would indeed start doing that, through a newly created Political Victory Fund.

The organization’s old guard, whose focus continued to be largely on hunting and sports shooting, was uncomfortable. Mr. Gutermuth, a conservationist with little political experience, wrote to a colleague that Mr. Dingell “wants an all out action program that goes way beyond what we think we dare sponsor.”

“John seems to think that we should become involved in partisan politics,” he said.

Mr. Dingell got his way. A 33-page document — “Plan for the Organization, Operation and Support of the NRA Institute for Legislative Action” — was wide-ranging. The proposal, largely written by Mr. Dingell, called for an unprecedented national lobbying push supported by grass-roots fund-raising, a media operation and opposition research.

Mr. Dingell made detailed arguments for why the N.R.A. was not doing enough to fight gun control efforts in the 1970s.

Mr. Dingell made detailed arguments for why the N.R.A. was not doing enough to fight gun control efforts in the 1970s.

It would “maintain files for each member of Congress and key members of the executive branch, relative to N.R.A. legislative interests,” and “using computerized data, bring influence to bear on elected officials.” The plan reflected Mr. Dingell’s savvy as a lawmaker: “For greatest effectiveness and economy, whenever possible, influence legislation at the lowest level of the legislative structure and at the earliest time.”

Walt Sanders, a former legislative director for Mr. Dingell, said the congressman viewed the N.R.A. as useful to his goal of protecting and expanding gun rights, particularly by heading off efforts to impose new restrictions.

“He believed very strongly that he could affect gun control legislation as a senior member of Congress and use the resources of the N.R.A. as leverage,” Mr. Sanders said.

The changes mirrored an increasingly uncompromising outlook within the N.R.A. membership. In what became known as the “Revolt at Cincinnati,” a group of hard-liners seized control of the group at its 1977 convention.

The coup drew inspiration from Mr. Dingell, who a month before had circulated a blistering attack on the incumbent leadership. He was revered by many members, who saw little distinction between his roles as a lawmaker and an N.R.A. director, and would write letters praising his fight on their behalf against “gun-grabbers.”

In his responses, he would sometimes correct the impression that he represented the N.R.A. in Congress.

“I try to keep my responsibilities in the two capacities separate so that there is no basic conflict,” he wrote to one constituent.

President Ronald Reagan waved to spectators in 1981, seconds before an assassination attempt outside a Hilton hotel in Washington

President Ronald Reagan waved to spectators in 1981, seconds before an assassination attempt outside a Hilton hotel in Washington

Cultural Shift

When gunshots claimed the life of John Lennon in December 1980 and nearly killed President Ronald Reagan a few months later, the N.R.A. readied itself for a familiar battle. Its officials, meeting in May 1981, grumbled that their “priorities, plans and activities have necessarily been altered.”

But remarkably, no new gun restrictions made it through Congress.

The group saw the failure of gun control efforts to gain traction as a validation of its new agenda and a sign that, with Reagan’s election, there was “a new mood in the country.” The N.R.A. and its congressional allies seized the moment, eventually pushing through the most significant pro-gun bill in history, the Firearms Owners’ Protection Act of 1986, which rolled backelements of the Gun Control Act.

The bill — largely written by Mr. Dingell but sponsored by Representative Harold L. Volkmer, a Missouri Democrat who would later join the N.R.A. board — was opposed by police groups. It lifted some restrictions on gun shows, sales of mail-order ammunition and the interstate transport of firearms.

The N.R.A. also went ahead with Mr. Dingell’s plans “to develop a legal climate that would preclude, or at least inhibit, serious consideration of many anti-gun proposals.” A strategy document from April 1983 laid out the long-term goal: “When a gun control case finally reaches the Supreme Court, we want Justices’ secretaries to find an existing background of law review articles and lower court cases espousing individual rights.”

The document listed several scholars the N.R.A. was supporting. Decades later, their work would be cited in the Supreme Court’s landmark 2008 decision in Heller, affirming gun ownership as an individual right. And it would surface in last year’s New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen ruling, which established a right to carry a firearm in public and a novel legal test weakening gun control efforts — prompting lower courts to invalidate restrictions on ownership by domestic abusers and on guns with serial numbers removed.

Mr. Dingell’s aides considered his options for trying to repeal the assault weapons ban in 1995.

Mr. Dingell’s aides considered his options for trying to repeal the assault weapons ban in 1995.

Key to those victories were appointments of conservative justices by N.R.A.-backed Republican presidents. By the time Antonin Scalia — author of the Heller opinion — was nominated by Reagan in 1986, the joke was that the “R” in N.R.A. stood for Republican, and internal documents from that era are laced with partisan rhetoric.

A 1983 report by a committee of N.R.A. members identified the perceived enemy as liberal elites: “college educated, intellectual, political, educational, legal, religious and also to some extent the business and financial leadership of the country,” inordinately affected by the assassinations of “men they admired” in the 1960s.

Lawmakers joining the board during that time — Mr. Ashbrook, Mr. Craig and Mr. Stevens — were all Republicans. Mr. Craig, a conservative gun enthusiast raised in a ranching family, would become “probably the most important” point person for the N.R.A. in Congress after Mr. Dingell, said David Keene, a longtime board member and former N.R.A. president.

“He was actually like having one of your own guys there,” Mr. Keene said in an interview.

He added, however, that a legislator need not have been a board member to be supportive of the group’s ambitions.

Mr. Craig did not respond to requests for comment, and Mr. Ashbrook and Mr. Stevens are dead. The N.R.A. did not respond to requests for comment.

President Bill Clinton handed James Brady a pen after signing the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, which imposed a background check requirement for gun purchases from licensed dealers.

President Bill Clinton handed James Brady a pen after signing the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, which imposed a background check requirement for gun purchases from licensed dealers.

Mr. Dingell, under increasing pressure as a pro-gun Democrat, faced a reckoning of sorts in 1994, when Congress took up an anti-crime bill that would ban certain semiautomatic rifles classified as assault weapons. He opposed the ban but favored the rest of the legislation.

A year earlier, he had angered fellow Democrats by voting against the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, which imposed a background check requirement. This time, after intense lobbying that included urgent calls from President Bill Clinton, Mr. Dingell lent crucial support for the new legislation — and resigned from the N.R.A. board.

His wife, Representative Debbie Dingell, a proponent of stronger gun laws who now occupies his old House seat, said her husband faced a backlash from pro-gun extremists that left him deeply disturbed.

“He had to have police protection for several months,” Ms. Dingell said in an interview. “We had people scream and yell at us. It was the first time I had seen that real hate.”

Despite voting for the ban, Mr. Dingell almost immediately explored getting it overturned. Notes from 1995 show his staff weighing support for a repeal proposal, conceding that “a solid explanation will have to be made to the majority of our voters who favor gun control.”

A memorial to the victims of the Columbine High School shooting in Littleton, Colorado.

A memorial to the victims of the Columbine High School shooting in Littleton, Colorado.

‘Best Foot Forward’

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold were too young to legally purchase a firearm, so in November 1998 they enlisted an 18-year-old friend to visit a gun show in Colorado and buy them two shotguns and a rifle. Five months later, they used the weapons, along with an illegally obtained handgun, to kill 12 students and one teacher at Columbine High School.

The massacre was a turning point for a country not yet numbed to mass shootings and for the N.R.A., criticized for pressing ahead about a week later with plans for its convention just miles from Columbine. That sort of response would be repeated years later, after a teenager killed 19 students and two teachers in Uvalde, Texas, and the N.R.A. went on with its convention in the state shortly afterward.

After Columbine, the organization mobilized against a renewed push for gun control. It had a new lawmaker-director to help: Mr. Barr, who had joined the board in 1997.

Mr. Barr congratulated Mr. LaPierre on his speech at the N.R.A.’s Denver convention after the Columbine shooting.

Mr. Barr congratulated Mr. LaPierre on his speech at the N.R.A.’s Denver convention after the Columbine shooting.

A staunchly conservative lawyer with a libertarian bent, Mr. Barr was among the House Republicans to lead the impeachment of Mr. Clinton. He served on the Judiciary Committee, which has major sway over gun legislation, and proved an eager addition to the N.R.A. leadership.

Mr. Barr wrote to another director with a standing offer to use his Capitol Hill office to ensure that any “information you have is cranked into the legislative equation.” Mr. Barr’s chief of staff sent the congressman a memo saying the gun group wanted him to review the agenda for a meeting on the “upcoming legislative session” and “make any changes or additions.”

The post-Columbine legislative battle centered on a bill to extend three-day background checks to private sales at gun shows, something the N.R.A. vigorously opposed, saying most weekend shows ended before a check could be completed. In the Senate, Mr. Craig engineered an amendment softening the impact, and Mr. Barr worked the House, earning them praise at an N.R.A. board meeting as “two people that put our best foot forward.”

The N.R.A. also turned to an old hand: Mr. Dingell.

Together, they came up with another amendment that narrowed the gun shows affected and required background checks to be completed in 24 hours or else the sale would go through. Publicly, Mr. Dingell argued that the shortened time window was reasonable.

But his papers include notes explaining that while most background checks are done quickly, some take up to three days because the buyer “has been charged with a crime” and court records are needed. Gun shows mostly happen on weekends, when courthouses “are, of course, closed.”

“It is becoming increasingly tougher to make our case that 24 hours is indeed enough time to do the check,” a member of Mr. Dingell’s staff wrote to an N.R.A. lobbyist.

Nevertheless, Mr. Dingell succeeded in amending the bill. He tried to win over his fellow Democrats with a baldly partisan message: “We’re doing this so that we can become the majority again. Very simply, we need Democrats who can carry the districts where these matters are voting issues.”

But his colleagues pulled their support. Representative Zoe Lofgren, a California Democrat who fought for the stronger bill, said she believed Mr. Dingell was “trying to make progress, and had, he felt, some credibility with the N.R.A. that might allow him to do that.”

“Even though what he wanted to do was far from what I wanted to do,” she said.

At the N.R.A., the collapse of the bill was seen as a victory. An internal report cited Mr. Dingell’s “masterful leadership.” A year later the group honored him with a “legislative achievement award.”

‘We Can Help’

Despite the victories, Mr. Barr saw bigger problems ahead. In memos to Mr. LaPierre in late 1999, he warned that the “entire debate on firearms has shifted” and advised holding an “issues summit.”

Specifically, he pointed to civil lawsuits seeking to hold the firearms industry liable for making and marketing guns used in violent crimes. Gun control advocates saw them as a way around the political stalemate in Washington — Smith & Wesson, for instance, chose to voluntarily adopt new standards to safeguard children and deter theft.

Mr. Barr had introduced a bill that would protect gun companies from such lawsuits, but lamented that “I have received absolutely zero interest, much less support, from the firearms industry.”

“We can help the industry through our efforts here in the Congress,” he wrote.

Mr. Craig took up the issue in the Senate, drafting legislation that mirrored Mr. Barr’s House bill. After Mr. Barr lost re-election in 2002, a new version of his liability law was sponsored by others, with N.R.A. guidance. To draw support from moderates, an incentive was added mandating that child safety locks be included when a handgun is sold, but N.R.A. talking points assured allies that the provision “does not require any gun owner to actually use the device.”

The N.R.A. board discussed how Mr. Craig helped scuttle an effort in Congress to require the use of gun safety locks.

The N.R.A. board discussed how Mr. Craig helped scuttle an effort in Congress to require the use of gun safety locks.

The political climate shifted enough under President George W. Bush and the Republican-controlled Congress that the assault weapons ban of 1994, which had a 10-year limit, was allowed to sunset, and the gun industry’s liability shield finally passed in 2005. The twin developments helped turbocharge the firearms market.

The private equity firm Cerberus Capital soon began buying up makers of AR-15 semiautomatic rifles and aggressively marketing them as manhood-affirming accessories, part of a sweeping change in the way military-style weapons were pitched to the public. The number of AR-15-type rifles produced and imported annually would skyrocket from 400,000 in 2006 to 2.8 million by 2020.

Asked about his early role in pressing the N.R.A. for help with the liability law, Mr. Barr said he believed the legal threat was significant enough “that the Congress step in.”

“The rights that are front and center for the N.R.A., the Second Amendment, are very much under attack and need to be defended,” Mr. Barr said. “And I defended them both as a member of Congress in that capacity and in my private capacity as a member of the N.R.A. board.”

Sensitivities

With each new mass shooting in the 2000s, pressure built on Congress to act, and the politics of gun rights became more polarized.

The N.R.A. lost another of its directors in Congress — Mr. Craig was arrested for lewd conduct in an airport men’s room and chose not to run again in 2008. But by then, the group’s aggressive use of campaign donations and candidate “report cards” had achieved a virtual lock on Republican caucuses.

That left Mr. Dingell increasingly marginalized in the gun debate. For a time, his connections were useful to Democrats; in 2007, after the shooting deaths of 32 people at Virginia Tech, he helped secure N.R.A. support to strengthen the collection of mental health records for background checks.

But by December 2012, when Adam Lanza, 20, shot to death 20 children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut, any vestige of good will between the N.R.A. and Democrats was gone. When House Democrats created a Gun Violence Prevention Task Force, they included the 86-year-old Mr. Dingell as one of 11 vice chairs, but his input was limited.

Notes from a task force meeting in January 2013 show that when it was Mr. Dingell’s turn to speak, he joked that he was the “skunk at the picnic” who had set up the N.R.A.’s lobbying operation — the “reason it’s so good.” He went on to underscore the rights of hunters and defend the N.R.A., saying it was “not the Devil.”

A few days earlier, he had privately conferred with N.R.A. representatives. Handwritten notes show that they discussed congressional support for new restrictions and the N.R.A.’s desire to delay legislation:

“Need to buy time to put together package can vote for, and get support, also for sensitivities to die down,” the notes said.

Mr. Dingell in 2014 with his wife, Debbie, a gun control advocate who would take over his seat in Congress.

Mr. Dingell in 2014 with his wife, Debbie, a gun control advocate who would take over his seat in Congress.

Three months later, a bipartisan gun control proposal failed after implacable resistance from the N.R.A. It was not until June 2022, after the Uvalde shooting, that a major firearms bill was passed — the first in almost 30 years. The legislation, which had minimal Republican support and fell far short of what Democrats had sought, required more private gun sellers to obtain licenses and perform background checks, and funded state “red flag” laws allowing the police to seize firearms from dangerous people.

By the time Mr. Dingell retired from the House in 2015, his views on gun policy had evolved, according to his wife, who said he no longer trusted the N.R.A.

“I can’t tell you how many nights I heard him talking to people about how the N.R.A. was going too far, how they didn’t understand the times,” Ms. Dingell said. “He was a deep believer in the Second Amendment, and at the end he still deeply believed, but he also saw the world was changing.”

In June 2016, after 49 people were killed in a mass shooting at an Orlando, Fla., nightclub, Ms. Dingell joined fellow Democrats in occupying the House floor as a protest. When she gave a speech, in the middle of the night, she broached the difference of opinion on guns she had with her husband.

“You all know how much I love John Dingell. He’s the most important thing in my life,” she said. “And yet for 35 years, there’s been a source of tension between the two of us.”

Mr. Dingell, too, briefly addressed that tension in a memoir published shortly before he died. He recalled that as he watched a recording of his wife’s speech the following morning, “I thought about all the votes I’d taken, all the bills I’d supported,” and “whether the gun debate had gotten too polarized.”

“As Debbie had said with such passion the night before, ‘Can’t we have a discussion?’” he wrote. “And I thought about the role I know I played in contributing to that polarization.”

Mike McIntire is a New York Times investigative reporter. He won a Pulitzer Prize in 2022 for his reporting on the hidden financial incentives behind police traffic stops, and has written in depth on campaign finance, gun violence and corruption in college sports. (The New York Times)

_________________________

It’s almost August.

Two supermoons in August mean double the stargazing fun.

The cosmos is offering up a double feature in August: a pair of supermoons. Catch the first show Tuesday night, Aug. 2, as the full moon rises in the southeast.

The cosmos is offering up a double feature in August: a pair of supermoons. Catch the first show Tuesday night, Aug. 2, as the full moon rises in the southeast.

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. (AP) — The cosmos is offering up a double feature in August: a pair of supermoons culminating in a rare blue moon.

Catch the first show Tuesday evening as the full moon rises in the southeast, appearing slightly brighter and bigger than normal. That’s because it will be closer than usual, just 222,159 miles (357,530 kilometers) away, thus the supermoon label.

The moon will be even closer the night of Aug. 30 — a scant 222,043 miles (357,344 kilometers) distant. Because it’s the second full moon in the same month, it will be what’s called a blue moon.

“Warm summer nights are the ideal time to watch the full moon rise in the eastern sky within minutes of sunset. And it happens twice in August,” said retired NASA astrophysicist Fred Espenak, dubbed Mr. Eclipse for his eclipse-chasing expertise.

The last time two full supermoons graced the sky in the same month was in 2018. It won’t happen again until 2037, according to Italian astronomer Gianluca Masi, founder of the Virtual Telescope Project.

Masi will provide a live webcast of Tuesday evening’s supermoon, as it rises over the Coliseum in Rome.

“My plans are to capture the beauty of this ... hopefully bringing the emotion of the show to our viewers,” Masi said in an email.

“The supermoon offers us a great opportunity to look up and discover the sky,” he added.

This year’s first supermoon was in July. The fourth and last will be in September. The two in August will be closer than either of those.

Provided clear skies, binoculars or backyard telescopes can enhance the experience, Espenak said, revealing such features as lunar maria — the dark plains formed by ancient volcanic lava flows — and rays emanating from lunar craters.

According to the Old Farmer’s Almanac, the August full moon is traditionally known as the sturgeon moon. That’s because of the abundance of that fish in the Great Lakes in August, hundreds of years ago.(Associated Press).

________________________