Labor Day. 👷♀️👷🏿👩🏽🍳👨🌾👩🎨👩🏼🚒 Monday, September 4, 2023. Annette’s News Roundup.

I think the Roundup makes people feel not so alone.

To read an article excerpted in this Roundup, click on its blue title. Each “blue” article is hyperlinked so you can read the whole article.

Please feel free to share.

Invite at least one other person to subscribe today! buttondown.email/AnnettesNewsRoundup

_____________________________

In Honor of Labor Day.

Letters from an American. Heather Cox Richardson.

On March 4, 1858, South Carolina senator James Henry Hammond rose to his feet to explain to the Senate how society worked. “In all social systems,” he said, “there must be a class to do the menial duties, to perform the drudgery of life.” That class, he said, needed little intellect and little skill, but it should be strong, docile, and loyal.

“Such a class you must have, or you would not have that other class which leads progress, civilization and refinement,” Hammond said. His workers were the “mud-sill” on which society rested, the same way that a stately house rested on wooden sills driven into the mud.

He told his northern colleagues that the South had perfected this system by enslavement based on race, while northerners pretended that they had abolished slavery. “Aye, the name, but not the thing,” he said. “[Y]our whole hireling class of manual laborers and ‘operatives,’ as you call them, are essentially slaves.”

While southern leaders had made sure to keep their enslaved people from political power, Hammond said, he warned that northerners had made the terrible mistake of giving their “slaves” the vote. As the majority, they could, if they only realized it, control society. Then “where would you be?” he asked. “Your society would be reconstructed, your government overthrown, your property divided, not…with arms…but by the quiet process of the ballot-box.”

He warned that it was only a matter of time before workers took over northern cities and began slaughtering men of property.

Hammond’s vision was of a world divided between the haves and the have-nots, where men of means commandeered the production of workers and justified that theft with the argument that such a concentration of wealth would allow superior men to move society forward. It was a vision that spoke for the South’s wealthy planter class—enslavers who held more than 50 of their Black neighbors in bondage and made up about 1% of the population—but such a vision didn’t even speak for the majority of white southerners, most of whom were much poorer than such a vision suggested.

And it certainly didn’t speak for northerners, to whom Hammond’s vision of a society divided between dim drudges and the rich and powerful was both troubling and deeply insulting.

On September 30, 1859, at the Wisconsin State Agricultural Fair, rising politician Abraham Lincoln answered Hammond’s vision of a society dominated by a few wealthy men. While the South Carolina enslaver argued that labor depended on capital to spur men to work, either by hiring them or enslaving them, Lincoln said there was an entirely different way to see the world.

Representing an economy in which most people worked directly on the land or water to pull wheat into wagons and fish into barrels, Lincoln believed that “[l]abor is prior to, and independent of, capital; that, in fact, capital is the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed—that labor can exist without capital, but that capital could never have existed without labor. Hence they hold that labor is the superior—greatly the superior of capital.”

A man who had, himself, worked his way up from poverty to prominence (while Hammond had married into money), Lincoln went on: “[T]he opponents of the ‘mud-sill’ theory insist that there is not…any such things as the free hired laborer being fixed to that condition for life.”

And then Lincoln articulated what would become the ideology of the fledgling Republican Party:

“The prudent, penniless beginner in the world, labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land, for himself; then labors on his own account for another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him. This, say its advocates, is free labor—the just and generous, and prosperous system, which opens the way for all—gives hope to all, and energy and progress, and improvement of condition to all.”

In such a worldview, everyone shared a harmony of interest. What was good for the individual worker was, ultimately, good for everyone. There was no conflict between labor and capital; capital was simply “pre-exerted labor.” Except for a few unproductive financiers and those who wasted their wealth on luxuries, everyone was part of the same harmonious system.

The protection of property was crucial to this system, but so was opposition to great accumulations of wealth. Levelers who wanted to confiscate property would upset this harmony, as Hammond warned, but so would rich men who sought to monopolize land, money, or the means of production.

If a few people took over most of a country’s money or resources, rising laborers would be forced to work for them forever or, at best, would have to pay exorbitant prices for the land or equipment they needed to become independent.

A lot of water has gone under the bridge since Lincoln’s day, but on this Labor Day weekend, it strikes me that the worldviews of men like Hammond and Lincoln are still fundamental to our society:

Should our government protect people of property as they exploit the majority so they can accumulate wealth and move society forward as they wish?

Or should we protect the right of ordinary Americans to build their own lives, making sure that no one can monopolize the country’s money and resources, with the expectation that their efforts will build society from the ground up? (September 2, 2023).

_____________________________

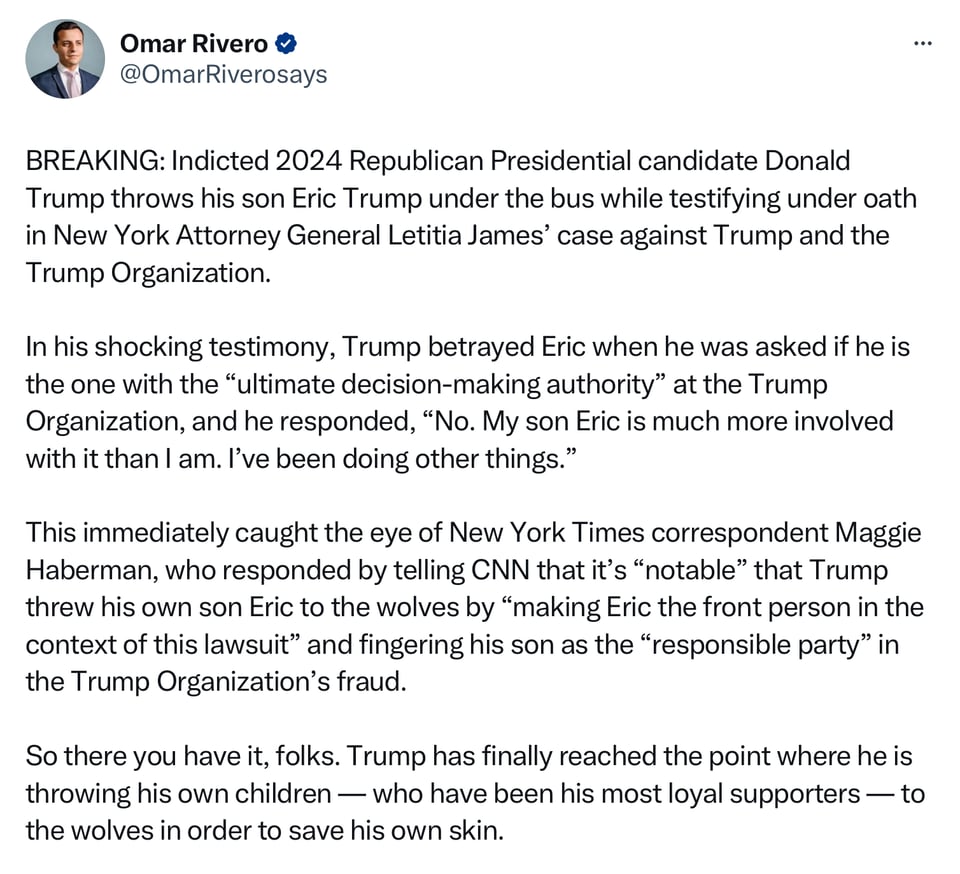

Trump has begun to throw others under the bus - “It was him, not me.” Unbelievable.

Victim #1.

Trump sat for a seven-hour deposition for Letitia James in April, and the transcript of that rambling and combative grilling is now public.

We learned that Trump threw his first victim under the bus. The victim was his own son, Eric.

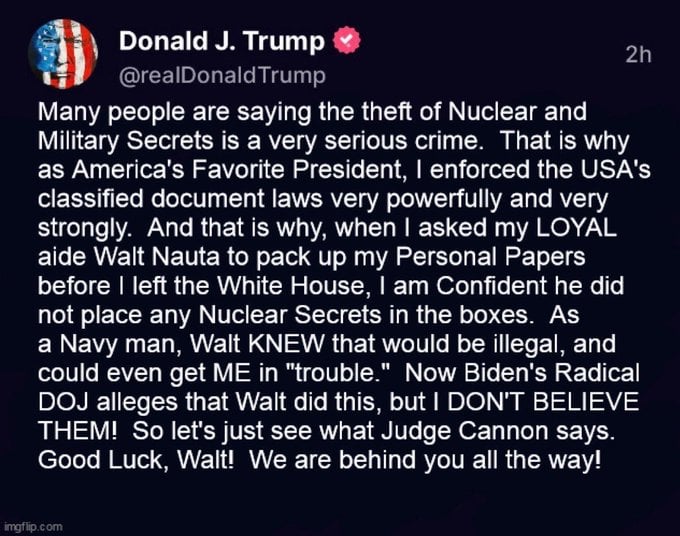

Victim #2.

On Saturday, Trump posted this Tweet on X - pointing 👉👉👉 at his victim, saying Walt Nauta was in charge.

The victim was his valet and co-defendant, Walt Nauta.

_____________________________

Bill Richardson, who brought home prisoners, has died.

Bill Richardson, Champion of Americans Held Overseas, Dies at 75.

Gov. Bill Richardson of New Mexico in his office in 2010. He served two terms, from 2003 to 2011, and was the nation’s only Hispanic governor.

Gov. Bill Richardson of New Mexico in his office in 2010. He served two terms, from 2003 to 2011, and was the nation’s only Hispanic governor.

Bill Richardson, who served two terms as governor of New Mexico and 14 years as a congressman, then continued to devote himself to liberating Americans who were being held hostage or who he believed were being wrongfully detained by hostile countries overseas, died on Friday at his summer home in Chatham, Mass., on Cape Cod. He was 75.

His death was announced by the Richardson Center for Global Engagement, which he founded. A cause was not given.

Under President Bill Clinton, Mr. Richardson was also ambassador to the United Nations, succeeding Madeleine Albright in early 1997, after having served in the House of Representatives, as a member of the New Mexico delegation, from January 1983 to February 1997 and as the chairman of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus. He was Mr. Clinton’s secretary of energy from 1998 until 2001.

Born in California — his mother had traveled to Pasadena from Mexico City, where the family was living, to give birth so there were would be no question about his citizenship — and descended from William Brewster, a passenger on the Mayflower, Mr. Richardson was the nation’s only Hispanic governor during his two terms, from 2003 to 2011.

Representative Gabe Vasquez, a New Mexico Democrat, described Mr. Richardson in a statement as “one of the most powerful Hispanics in politics that this nation has seen.”

But his home-state popularity — he was re-elected in 2006 by a 68 percent to 32 percent margin, a record for New Mexico — did not translate into national office.

In 2008, Mr. Richardson mounted a short-lived campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination but finished fourth in the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary. Despite having served in the Clinton administration, he endorsed Barack Obama over Hillary Clinton.

After winning the presidency, Mr. Obama nominated Mr. Richardson as secretary of commerce, but Mr. Richardson withdrew because of a pending investigation into allegations of improper business dealings in his home state. No charges were ever filed against him, and the investigation was later dropped.

After Mr. Richardson completed his second term as governor, he honed the quasi-public and freelance diplomacy skills that he had learned first in college and further developed on the staff of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and when he worked on congressional relations for the State Department under Henry Kissinger.

His separate humanitarian missions on behalf of some 80 families won the release of hostages and American servicemen in countries hostile to the United States, including Iraq, Afghanistan, Cuba and Colombia.

“I plead guilty to photo ops and getting human beings rescued and improving the lives of human beings,” he once said.

In 2006, he persuaded President Omar al-Bashir of Sudan to free the Pulitzer Prize-winning American journalist Paul Salopek.

The next year, he went to North Korea to recover the remains of American soldiers killed in the Korean War.

He helped negotiate the release of Michael White, a Navy veteran who was freed by Iran in 2020; flew to Moscow for a meeting with Russian government officials in the months before the release last year of Trevor Reed, a Marine veteran, in a prisoner swap; and worked on the case of Brittney Griner, the W.N.B.A. star who was held prisoner and later released by Moscow.

He also helped secure the 2021 release of the American journalist Danny Fenster from a Myanmar prison and this year negotiated the freedom of Taylor Dudley, who had crossed the border from Poland into Russia.

After conferring with autocrats including Saddam Hussein and Fidel Castro, Mr. Richardson once described himself as “the informal under secretary for thugs.” He put it more diplomatically in the title of a 2013 book: “How to Sweet-Talk a Shark: Strategies and Stories From a Master Negotiator.” (He also wrote a memoir, “Between Worlds: The Making of an American Life,” published in 2005.)

“There was no person that Governor Richardson would not speak with if it held the promise of returning a person to freedom,” Mickey Bergman, the vice president of the Richardson Center, said in a statement.

Given all of Mr. Richardson’s public offices, the center said in a statement, his enduring legacy would be his participation “in ‘fringe diplomacy’ to open the doors of negotiation with foreign parties to bring home those detained.”

William Blaine Richardson III was born on Nov. 15, 1947, in Pasadena. His father, who was of Anglo-American and Mexican descent, was a bank executive from Boston who worked in Mexico for what is now Citibank and had been born on a ship en route to Nicaragua when his own father, a biologist, was on his way to collect museum specimens.

“My father had a complex about not having been born in the United States,” Mr. Richardson told The Washington Post in 2007.

That was why his mother, Maria Luisa Lopez-Collada Marquez, the daughter of a Mexican mother and a Spanish father who had been his father’s secretary, was dispatched to California to give birth to Bill.

When he was 13, Bill was sent to the United States and attended Middlesex School in Concord, Mass. He earned a bachelor’s degree in French and political science in 1970 from Tufts University in Middlesex County, Mass. — he also pitched in the Cape Cod League — and a master’s in international affairs in 1971 from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts.

In 1972, he married Barbara Flavin, whom he had met in high school. She survives him. His survivors also include their daughter, Heather Blaine Richardson.

After working in Washington, Mr. Richardson had become smitten with politics and moved to New Mexico, where, given his Hispanic heritage, he figured he had the greatest chance of being elected to public office. He ran for Congress in 1980 and lost — his only electoral defeat until the 2008 presidential race — but was elected from a new district covering northern New Mexico in 1980.

While in Congress, he sponsored a number of bills on Native American rights.

His record as energy secretary was mixed. He presided during a period when computer equipment containing nuclear-weapons secrets went missing at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, as well as during the government’s botched investigation and firing of Wen Ho Lee. a former weapons scientist who spent nine months in solitary confinement for mishandling sensitive information — only to plead guilty to one count of mishandling computer files and receive an apology from a federal judge.

Mr. Richardson set more efficient energy standards for air-conditioners and other appliances, established the National Nuclear Security Administration, implemented a nuclear waste disposal plan, and oversaw the return of 84,000 acres of federal land to the Northern Ute tribe of Utah.

As governor, he raised teachers’ salaries, abolished the death penalty, signed legislation to allow New Mexicans to carry concealed handguns, established a fund to pay for public works, supported gay rights, raised the minimum wage and offered prekindergarten programs for 4-year-olds. But he declined to pardon William H. Bonney, known as Billy the Kid, for killing a New Mexico sheriff 130 years earlier. (Mr. Bonney was said to have been promised a pardon if he testified in another case.)

Mr. Richardson said of his two terms as governor: “It’s the most fun. You can get the most done. You set the agenda.”

In 1997, when he was at the United Nations, Mr. Richardson was asked by the White House to interview Monica Lewinsky, the White House intern who would figure in Mr. Clinton’s impeachment, and who wanted to return to New York from Washington, for a job. He was said to have offered her one, which she declined.

He usually got his way, though, as a result of relentless bargaining and a gregarious personality.

In his first campaign for governor, he set a Guinness World Record by shaking 13,392 hands in eight hours at the New Mexico State Fair. And the lengths to which he went to impress the president who appointed him U.N. ambassador became the stuff of legend. Those means were not necessarily always intentional.

In December 1996, he helped free three aid workers, an American, an Australian and a Kenyan, who were being held in Sudan, which the United States had declared a terrorist state, after persuading rebel leaders to drop their demand for millions of dollars in ransom money and agree instead to trade the prisoners for rice, Jeeps, radios and a health survey of their disease-ridden camp.

When Mr. Richardson returned to Washington to brief President Clinton on the negotiations, prominent on the president’s desk in the Oval Office was a copy of The New York Times’s article about the hostage affair.

It vividly described a negotiating table attended by barefoot, rifle-toting boys and a retinue of observers, including vultures, which perched on the roofs of thatched huts as a goat was being roasted nearby.

As Mr. Richardson later told the New York Times reporter Tim Weiner, the president asked him, “Did y’all eat the goat?” Mr. Richardson allowed that, indeed, he had.

Mr. Clinton smiled and asked, “How’d you like to be ambassador to the United Nations?” (New York Times).

Bill Richardson Reveled in Role of Freelance Envoy to Dictators.

Bill Richardson arriving at the Doha, Qatar, airport in 2021 with the U.S. journalist Danny Fenster, who had been imprisoned in Myanmar.

Bill Richardson arriving at the Doha, Qatar, airport in 2021 with the U.S. journalist Danny Fenster, who had been imprisoned in Myanmar.

It was days before Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, and the U.S. government was urging Americans to stay away from Russia. That’s when Bill Richardson boarded a plane to Moscow.

The former New Mexico congressman, governor and cabinet member was pursuing his passion: freelance diplomacy with a dangerous foreign government. In this case, Mr. Richardson was headed to the Russian capital in an effort to secure the release of Trevor Reed, a former U.S. Marine who the State Department said was wrongfully imprisoned. In a call to Mr. Reed’s parents, an aide to Mr. Richardson said his boss was on a “guerrilla mission,” they would later recall.

Two months later, Mr. Reed was freed in a prisoner exchange with Russia, one that his parents said would not have been possible without Mr. Richardson’s help — even if it was unclear whether the garrulous politician had made a decisive difference, as opposed to quiet negotiations by the Biden administration.

Either way, the Russian mission was classic Bill Richardson. Until his death on Friday at age 75, Mr. Richardson cultivated a unique specialty in foreign affairs, positioning himself as an emissary — sometimes a secret one, and not always a welcome one for U.S. officials — to brutish foreign leaders whom American presidents and other officials would or could not deal with directly.

In a statement on Saturday, President Biden called Mr. Richardson’s work to help bring home dozens of imprisoned Americans “perhaps his most lasting legacy.”

It was a role for which Mr. Richardson was stylistically well-suited. He had a flair for flattery, as well as a quick, self-deprecating humor. Asked in a 2016 public appearance how he had become a middleman to strongmen, he smiled as he quoted what he said was President Bill Clinton’s answer to that question: “Bad people like him.”

Over several decades, beginning in the 1990s, Mr. Richardson became known as something of a dictator whisperer, meeting with the likes of Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, Cuba’s Fidel Castro and more than one member of North Korea’s ruling Kim dynasty. Several of his trips are widely credited with winning the freedom of detained Americans whose release had not been possible to secure through official channels, whether for practical or political reasons.

He took pride in knowing how to negotiate with prideful, sometimes murderous men, writing a book entitled “How to Sweet-Talk a Shark.” (“Respect the other side. Try to connect personally. Use sense of humor. Let the other side save face,” he once told an audience.)

President Bill Clinton sent Mr. Richardson, then a congressman, to visit Saddam Hussein in Baghdad in 1995 in an effort to secure the release of two American prisoners. Credit...Iraqi News Agency, via Associated Press.

President Bill Clinton sent Mr. Richardson, then a congressman, to visit Saddam Hussein in Baghdad in 1995 in an effort to secure the release of two American prisoners. Credit...Iraqi News Agency, via Associated Press.

Some U.S. officials have quietly complained in recent years that Mr. Richardson’s freelance bargaining, however well-intentioned, had complicated official negotiations to secure the release of American prisoners.

Operating from his nonprofit, the Richardson Center for Global Engagement — which, despite the impressive name, occupied a modest office space in downtown Santa Fe — Mr. Richardson also provided advice and emotional support for the families of Americans who experts say have been wrongfully detained by hostile governments in growing numbers.

He was drawn into the shadowy and often morally fraught world of prisoner diplomacy as a New Mexico congressman in 1994, after an Army helicopter pilot was downed and captured by North Korea after straying across the country’s demilitarized border zone on a training mission. The pilot was a constituent of Mr. Richardson’s, and the representative spent several days in Pyongyang securing his release, as well as the remains of his fallen co-pilot.

“I think the North Koreans were so sick of me, they gave me the pilots because they wanted me to leave,” Mr. Richardson later joked.

Mr. Clinton was impressed with his efforts and, in what Mr. Richardson called “a domino effect,” later sent Mr. Richardson on delicate missions to places like Afghanistan and Sudan.

A behind-the-scenes illustration of Mr. Richardson’s method can be found in a transcript of his July 1995 meeting in Baghdad with Mr. Hussein, whom he visited in a Clinton-approved effort to secure the release of two American prisoners. (The transcript is one of hundreds of Iraqi documents captured by U.S. forces years later and posted online by the Department of Defense.)

The transcript shows Mr. Richardson to be copiously respectful of the Iraqi leader, noting that he had voted against the 1991 congressional authorization for the American military operation to expel Iraq from Kuwait. He also jokes that Baghdad’s ferociously hot summer weather reminds him of his native New Mexico.

Mr. Richardson then tells the Iraqi leader, “If we want my mission to be successful, it has to be done in extreme secrecy.” He adds that, while he is not an official emissary of the Clinton administration, Mr. Clinton “is very much aware of my visit, as I have spoken with him about it many times.” Without mentioning specific concessions, Mr. Richardson makes clear that granting clemency for the two prisoners would “create an atmosphere of good will in the United States” for Mr. Hussein.

“I apologize if I took too long talking, even though I promised not to do so,” he concludes, joking that he had been compensating for his party’s minority status in Congress.

The pitch worked: Mr. Hussein agreed to let Mr. Richardson bring the prisoners home. In return, according to the Iraqi government transcript, Mr. Richardson left him with a piece of handcrafted New Mexican pottery.

Mr. Clinton, who nominated Mr. Richardson to be his ambassador to the United Nations the next year, saidthat he had “undertaken the toughest and most delicate diplomacy around the world,” and marveled that just a few days earlier, Mr. Richardson “was huddled in a rebel chieftain’s hut in Sudan, eating barbecued goat and negotiating the freedom of three hostages.”

After finishing his term as New Mexico governor and leaving the national political stage, Mr. Richardson resumed his focus on American hostages and prisoners abroad. But in recent years, his work became increasingly independent of the U.S. government. And his role in U.S. negotiations with countries like Iran (helping secure the release of Michael White, a Navy veteran, in 2020), Myanmar (helping negotiate the freedom of the U.S. journalist Danny Fenster in 2021) and Russia became a source of tension with both the Trump and the Biden administrations.

As in the case of Mr. Reed, Mr. Richardson met with Russians — including an oligarch close to Russian president Vladimir Putin — to craft a deal for the release of two other Americans detained in Russia, the W.N.B.A. star Brittney Griner and the former U.S. Marine Paul Whelan. Ms. Griner was released as part of a prisoner swap in December, though, once again, U.S. officials gave no indication that Mr. Richardson had played a decisive role.

Speaking to CNN last year, Mr. Richardson dismissed talk that his freelance diplomacy might complicate work through official channels

“There are a lot of nervous Nellies in the government that think they could know it all, and that’s not the case,” he said. “Look at my track record over 30 years.” (New York Times).

Statement from President Clinton and Secretary Clinton on the Passing of Governor Bill Richardson pic.twitter.com/xiOYO2v9NT

— Angel Ureña (@angelurena) September 2, 2023

_____________________________

Happy Labor Day, our national day celebrating working men and women.

Hope yours is good.

See you tomorrow.

_____________________________