Friday, September 5, 2025. Annette’s Roundup for Democracy.

Let’s win this lawsuit and stop our dear leader.

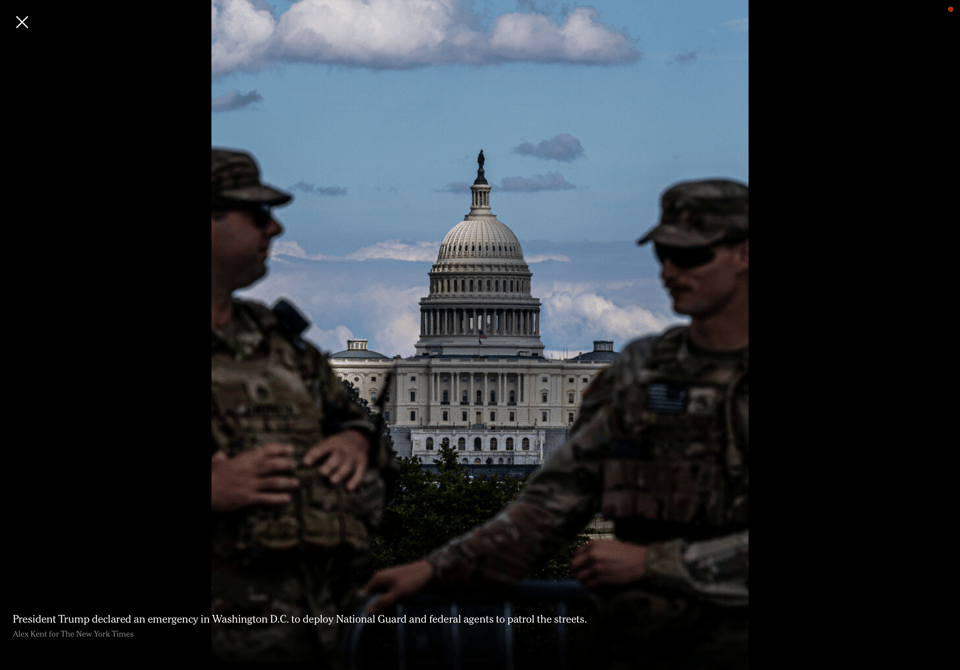

D.C. Sues Trump Administration Over Deployment of National Guard.

The city is challenging the federal government’s authority to send troops into the city for what the president has called a “public safety emergency.”

The District of Columbia sued the Trump administration in federal court on Thursday, challenging the president’s deployment of National Guard troops in the city.

Thousands of Guard members from the city and seven states were mobilized last month as part of a sweeping federal intervention that has also brought hundreds of federal law enforcement agents to the city’s streets.

The intervention, which President Trump has said is a response to a “public safety emergency,” has prompted criticism and protests from many people in the city who say the president wants to use his power of the federal enclave to roll back the city’s limited self-governance and punish it for policies he objects to.

The lawsuit by Washington comes two days after a federal judge in California ruled that the president’s decision to send National Guard soldiers to Los Angeles was illegal.

Abigail Jackson, a White House spokeswoman, said in a statement that the lawsuit was “nothing more than another attempt — at the detriment of D.C. residents and visitors — to undermine the President’s highly successful operations to stop violent crime in D.C.”

Even as the Guard deployments have faced local pushback and legal challenges, Mr. Trump has been promising to send troops to other cities, including Baltimore and Chicago. Like Washington and Los Angeles, Baltimore and Chicago are led by mayors who are Black and are Democrats.

“No American city should have the US military — particularly out-of-state military who are not accountable to the residents and untrained in local law enforcement — policing its streets,” Brian Schwalb, D.C.’s attorney general, said in a statement. “We’ve filed this action to put an end to this illegal federal overreach.”

Unlike in states, where governors have considerable authority over the deployment of the state guard, the D.C. National Guard is under the president’s direct command.

But the suit argues that the deployment of the local guard for public safety reasons, and without the mayor’s consent, violated Washington’s autonomy under the 52-year-old Home Rule Act.

The suit also makes an argument similar to the one the judge in California based his ruling on: that the deployment of National Guard troops in the city runs “roughshod over a fundamental tenet of American democracy — that the military should not be involved in domestic law enforcement.”

Mr. Trump had made clear that such a role was his intention, saying on Aug. 11 that he was calling out the Guard to “reestablish law, order and public safety” in the city. Since then, even as federal law enforcement officers have been involved in hundreds of arrests and immigration agents have been detaining hundreds of Washington residents deemed to be in the country illegally, the National Guard troops have been posted at Metro stations and around city landmarks. Some soldiers have been seen picking up trash.

The suit is the second the city has filed against the administration since Mr. Trump declared a “public safety emergency” in the city.

The first, filed days after the declaration, challenged the authority of the administration to take command of the D.C. police. The city appeared likely to prevail, given the judge’s comments during the initial hearing, but that ended with the U.S. Attorney General agreeing to take a more limited role in compelling local police to cooperate on certain tasks. (New York Times).

One more thing.

Why Trump’s Threat to Send Troops to Chicago Is So Dangerous

If President Donald Trump follows through on threats to send the National Guard to Chicago, his decision will not only stress-test the deep American antipathy to military rule. It will also generate a cascade of legal challenges with few precedents.

Trump may float New Orleans as his next target, but a deployment of the guard to Chicago over the objections of a Democratic governor raises two broad categories of legal question: Is the deployment legal, and are actions taken during a deployment criminal or unconstitutional? The first question, already a subject of litigation over Trump’s Los Angeles troop deployment, is mired in legal complexities, but it boils down to whether the courts will blink when confronted with blatant lies about the deployment’s rationale. The second question is easy to overlook, but vital in practice, because it illuminates the immediate stakes of expansive Guard deployment in the homeland.

Let’s go in reverse order, so those stakes are clear up front. Imagine the president lawfully takes control of a state National Guard, which is known as “federalizing” it, and which has occurred occasionally throughout American history. Such a move, importantly, doesn’t automatically tap any new substantive authority to conduct arrests, make searches or control people’s movement. In theory, if federalized troops conduct illegal arrests or searches, or if they stifle political speech, they violate the Constitution and can be held to account.

But in practice, matters are different. For one thing, the Trump administration would be unlikely to prosecute the very troops it activated under the criminal provisions of the civil rights laws. Meanwhile, the risk of unconstitutional violence ticks up when local police are displaced. Chicago police, for example, negotiated a consent decree in 2021 setting out rules for First-Amendment-protected protests. Both cops and civil society have clear guardrails, which are well-used and familiar to locals after four years of use. But those rules are not binding on the National Guard. What’s more, those troops — many molded by combat experience overseas — have no training for domestic engagements. Without rules, without experience, the risk that a misunderstanding sparks a conflagration is grave.

Worse, the Rehnquist and Roberts Courts have chipped away at the mechanisms to redress such harms. Damages, injunctions, habeas corpus writs or orders to exclude evidence — all these technically exist, but in practice are beyond most people’s reach.

This reality makes domestic deployment of the military a particular threat to constitutional rights, and in particular to the First Amendment activities of organizing, protesting and even speaking. Imagine federal forces policing protests of election fraud, or regulating which candidates can hold rallies in the runup to the midterms, and it becomes clear why what’s at stake is not just individuals’ civil rights: It is the integrity of the democratic process.

All this makes the first question more pressing: If there are few after-the-fact controls on unconstitutional federal violence, then surely the legal frameworks determining when troops can be deployed in the homeland should be carefully calibrated with a clear threshold and sharply etched boundaries.

Alas, the statutes that regulate domestic uses of the military are tangled, vaguely and carelessly framed and riddled with incoherences. The legal theory underlying the deployment of troops in Washington, D.C., was different from the one used for L.A. — and there is no certainty the same theory will be re-upped for Chicago.

Much of this ambiguity bubbles out of an 1878 statute called the Posse Comitatus Act. Ironically, it was first adopted to limit the federal government’s military enforcement of the Fourteenth Amendment, thus enabling the birth of Jim Crow. At least in theory, the law prohibits the president from unilaterally using troops to engage in policing or law enforcement—and so has become a bulwark for American citizens’ freedom from military subjugation.

Yet the Posse Comitatus Act’s riddled with gaps. For example, the 1878 measure only applies to the National Guard when they are fully “federalized,” rather than in “state active duty” status. Hence, the D.C. National Guard — which is commanded by the president — can, and in recent weeks has been, mobilized in its “state” form without triggering the law. Indeed, a recent executive order envisages creation of a more permanent “specialized unit” — perhaps capable of deployment beyond the Beltway.

Moreover, the Act bars troops from “executing the law,” but doesn’t define that term. So when the National Guard are called upon to surround a federal building during a protest, is that “executing the law” or is it merely acting in a protective manner? The law doesn’t say, but it’s easy to see how the second function could swallow the first, especially if read by a pro-presidential Supreme Court.

Worse, the 1878 Act allows for deployments when there is an “exception” in another statute — and there are at least 26 other statutes that act as such escape hatches. Some are barely relevant today, but there remains a smorgasbord of statutory options for a federal lawyer looking for ways to use the military. From the perspective of blue-state mayors and governors, this creates abiding uncertainty about not just whether, but also where and how, federal troops will be deployed.

What authority would Trump use for a potential Chicago deployment? One possibility is that he involves one of the five so-called Insurrection Acts passed between 1792 and 1871. One of the most sweeping of these allows the president to use the military when he sees “obstructions” that “make it impracticable to enforce the laws of the United States.” Taken literally, this seems like an open invitation to cast aside civilian law enforcement whenever the president thinks it convenient. Unless the courts were willing to check aggressively the meaning of words like “obstructions” and “impracticable,” this is an exception that could easily overtake the rule.

Yet Trump to date has not invoked that provision. Perhaps his lawyers recognize that it poses hard questions about vast delegations of untrammeled authority of a sort that have caught the Roberts Court’s attention elsewhere.

Instead, in the L.A. deployment, it leaned on a different, two-step theory. First, the government used a slightly narrower provision, which allows the president to federalize the National Guard when he is “unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States.” This provision, moreover, requires that orders to the Guard be “issued through the governors,” language added in 1908 to the statute seemingly to ensure that this power could not be used over a state’s consent.

If Trump uses this narrower provision again, a threshold question will be whether the president is in fact “unable” to enforce federal law. In the L.A. case, a panel of appellate federal judges found there was enough evidence of violent disruption to ICE enforcement actions to trigger deployment authority. That factual conclusion is, at a minimum, highly debatable, even under its highly president-friendly reading of the statute.

And in cities such as Chicago, with no riots or massive protests against ICE enforcement, there is simply no pattern of obstructed federal functionalities which the government could cite. It would rather have to make the bald, fact-free assertion, that the president felt “unable” to act.

But even assuming that the Guard is lawfully federalized, this does not mean that the military can be used for law enforcement. The provision allowing the National Guard to be federalized has never been understood as an exception to the Posse Comitatus Act — and so whatever the Guard then does cannot be law enforcement. It was on this basis that Judge Charles Breyer ruled this week that Trump had violated the Posse Comitatus Act by using troops in L.A. to do security patrols, crowd control and traffic enforcement.

If a further deployment happens, however, the executive will likely claim federalization is lawful, and no law enforcement is occurring in violation of Posse Commitatus. Given what’s happened so far, both claims are likely be dubious. So the question will be become whether judges charged with enforcing the law — all the way up to the Supreme Court — would be willing to stomach what is likely to be an out-and-out lie to avoid a confrontation with the president.

Here, the historical record is hardly comforting. At least twice before in cases concerning Trump, the Supreme Court has managed to simply ignore evidence of unlawful discriminatory motive or outright criminality on dubious theoretical grounds. There’s little reason now to expect the justices to act like actual judges by standing up to presidential lies, as opposed to serving as rubber stamps.

Given a bench subservient to a politically aligned president, it’s hard to see how a new National Guard deployment ends well. Not only the people of Chicago, but the strength of American democracy, are likely to face real harm. (Aziz Z. Huq, an American legal scholar who is the Frank and Bernice J. Greenberg Professor of Law at the University of Chicago Law School. Politico.)

Maybe someone should warn Trump. “Shouting fire in a crowded theater” is a Class E felony.

Can Trump Just Do Whatever He Wants by Declaring Emergencies?

He’s exploiting a diabolical problem in our legal system to expand presidential power.

President Trump declared an emergency in Washington D.C. to deploy National Guard and federal agents to patrol the streets.

The United States is a nation in crisis, President Trump says. The problems are both profound and urgent. He knows how to fix them, but his ideas are hard to implement: They require new legislation or lumbering legal petitions. Luckily, there’s an easier way. The law often gives the president new and broad powers in a state of emergency.

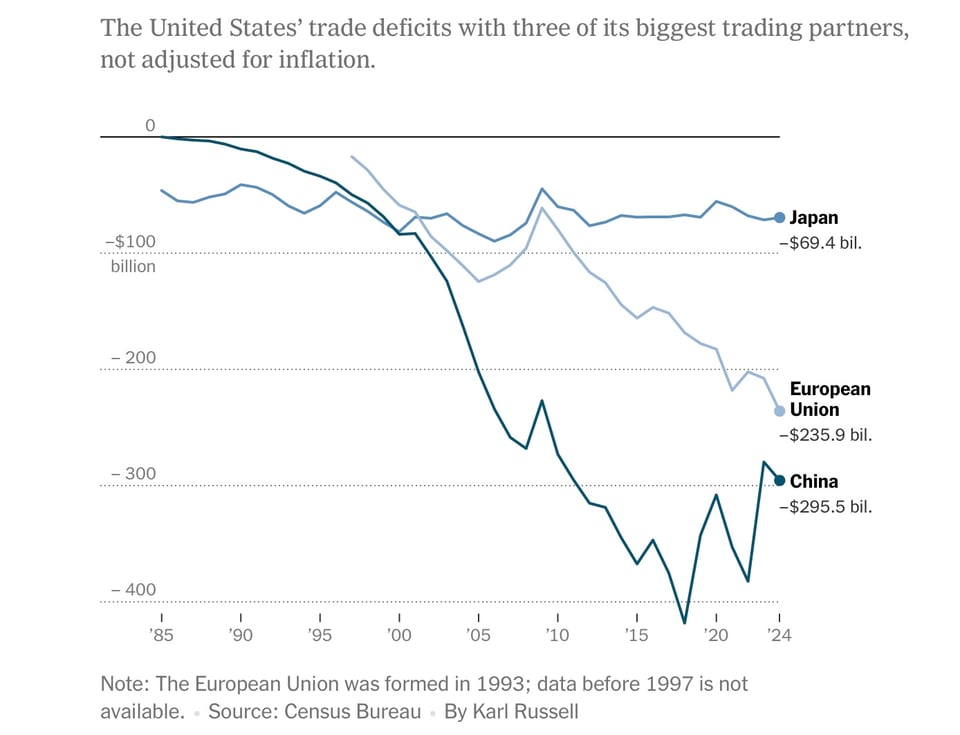

So he has declared nearly a dozen. Trump says he can impose tariffs because he says it’s an emergency to contain trade deficits. He can deport immigrants without due process because it’s an emergency to fight a Venezuelan gang’s invasion. He can dispatch the National Guard to American cities like Los Angeles because it’s an emergency to quell protests and crime. He can ask the Supreme Court for emergency rulings on legal challenges to his authority because we can’t afford to wait for judges to debate his policies.

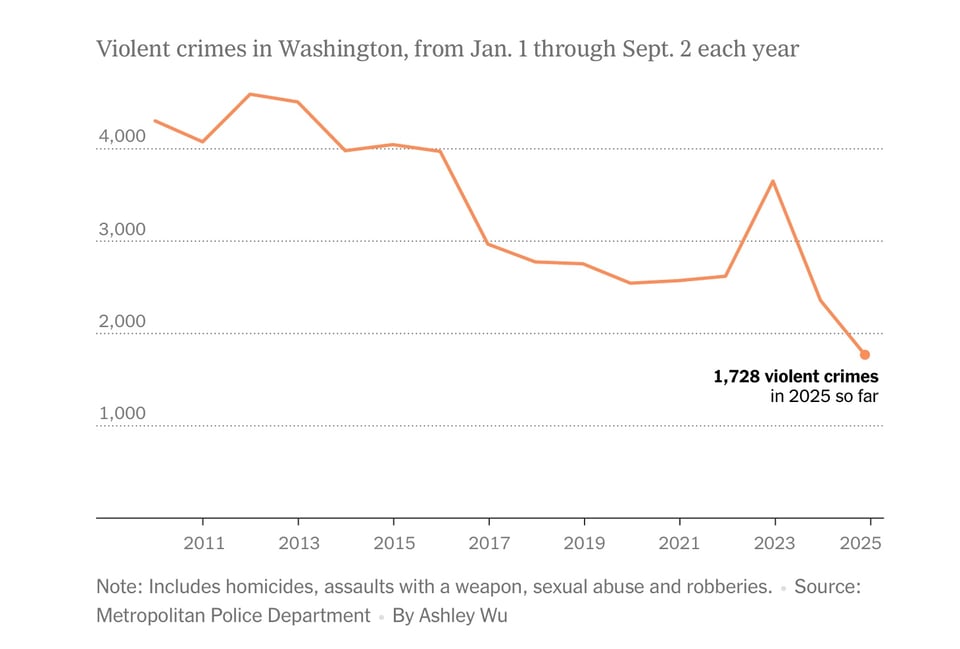

All this exposes a diabolical problem in our legal order: An emergency is in the eye of the beholder. Do these problems of debatable urgency demand an immediate response? The trade imbalance is generations old. Immigrants — even foreign gangs — are not an invading army. Protesters aren’t rebels. Crime has plunged nationwide, including in all of the cities Trump says need urgent protection. He could wait for courts to decide if he has the power to remake the government, as his predecessors generally have.

Invoking emergencies lets the president have his way, now. If there is a dire new threat and our laws and norms can’t protect us from it, then serious leadership requires the suspension of normalcy. That’s the pitch, anyway. “Violent, insurrectionist mobs are swarming and attacking our Federal Agents,” he posted online when he deployed troops to California. “Harvard is a threat to Democracy,” he said in explaining his intervention there.

It’s not a new idea. “We tend to associate autocracy with emergency,” says Kim Lane Scheppele, a Princeton professor who studies the rise and fall of democracy. Ferdinand Marcos cited a communist insurgency in the Philippines to grab the reins; Recep Tayyip Erdogan blamed a failed military coup in Turkey as his reason to rule by decree for two years; Viktor Orban justifies his suppression of civil rights in Hungary by pointing to Covid, Ukraine and immigration emergencies.

Carl Schmitt, a Nazi political theorist, wrote extensively on the “state of exception.” The main attribute of a sovereign leader, he argued, was the ability to pause the normal legal order during a time of crisis. Schmitt’s idea vexed liberals because it took advantage of the liberal, rules-based system: A president could win a legitimate election, follow the laws, govern normally — and then, at any point, declare a state of exception that suspends those laws.

Yet the emergency, in Trump’s hands, isn’t just a legal declaration. It’s a philosophy of governing. In his telling, political emergencies also let him impound funds allocated by Congress, close federal agencies, remake American museums and attempt to control the Federal Reserve.

“You never want a serious crisis to go to waste,” President Barack Obama’s chief of staff said during the 2008 financial crash. “It provides the opportunity to do things that were inconceivable before.” The difference is that the mortgage crisis was a once-in-a-generation economic catastrophe. By describing so many things as an emergency today, Trump signals that he must take abnormal action to cope with an abnormal time. In a climate of emergency, it seems, anything is possible.

The law

Most democracies have emergency measures in their constitutions. An executive can declare a state of emergency that starts a clock. He or she may have extraordinary powers for a time, especially over security — and can sometimes even suspend certain civil rights. But the legislature can override the leader. And when time’s up, the legislature decides whether to renew the emergency or end it. The leaders of France and Chile, for instance, used such powers to deal with Covid.

The U.S. Constitution doesn’t have a general emergency authority. Instead, we have a web of laws that give the president special powers in specific circumstances. Trump has relied upon that web of laws in a systematic way that none of his peacetime predecessors did. “These have accumulated over time to the point where, if you invoke an emergency in area after area after area, you can grope your way toward something resembling a general emergency power,” says David Pozen, a constitutional expert at Columbia Law School.

Trump has used 10 emergency declarations to justify hundreds of actions. Consider:

The Alien Enemies Act of 1798 empowers the president to quickly deport foreigners during a war or an invasion — but doesn’t say what an invasion is. The Homeland Security Department says it is battling an invasion by Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan gang. An appeals court said this week that the administration isn’t using the law properly, though the government has already deported many people that way. The question is headed for the Supreme Court.

The International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 says the president can take action against an “unusual and extraordinary threat.” But the trade deficit Trump cites as the reason for his tariffs is usual and ordinary. An appeals court said last week that tariffs imposed by executive order were illegal, but Trump is appealing to the Supreme Court.

U.S. law lets the president deploy the National Guard domestically to help enforce federal law. Were federal buildings and immigration agents really unsafe because Angelenos were protesting an immigration crackdown? On Tuesday, a federal district judge in California called the deployment there illegal because the demonstrations were not “a form of rebellion,” as the government claimed.

When legislators drafted those statutes, they assumed that presidents would invoke their laws in good faith. They set out preconditions — an invasion, a rebellion, a national security threat — but left the president a wide berth to define those things. How closely do migrant criminals need to be tied to a foreign government to be called invaders? Intelligence agencies say that Venezuela does not control Tren de Aragua, but the administration simply asserts that it does, and that may be enough for the high court.

Judges are now being forced to decide whether Trump’s emergencies are genuine. They’re historically bad at this. “It’s striking how little policing of bad faith courts do,” Pozen says. “They’re working with limited precedent, vague statutory language and a tradition of deference to the executive branch, all of which potentially cut in Trump’s favor.” A legal tradition called “the presumption of regularity” also means that judges assume the government is acting honestly (though a few judges have begun to wonder).

In Washington, D.C., Trump used a local law that lets him take over the police force in a “crime emergency.” There is crime; it has been falling. But Washington was a “sanctuary city” where the police refused to cooperate with federal immigration agents. Now those agents are in town and deporting illegal immigrants.

In this way, the president has immense power to define reality. A dissent in the trade case made the argument explicit: A president’s factual claims “are not subject to objective proof of error.”

Trump has other advantages when it comes to the judiciary. Power in the United States has shifted in recent decades from the legislative branch to the executive branch. Republicans have advanced judicial nominees who like that development, Scheppele says. “They see the Constitution through the perspective of the executive branch doing what it wants to do.”

The problem for Democrats, cities, illegal immigrants and companies that want to challenge Trump is that the conservative majority on the Supreme Court already shows him exceptional deference. In the presidential immunity case last year, it found that Trump generally can’t be prosecuted for official acts. Now, in a raft of emergency challenges, the court has said he can impose policies that lower courts have paused. He needn’t wait for cumbersome appeals about the legality of gutting the Education Department or firing National Labor Relations Board members, for example. He can just do it; they’ll address the legality later, if at all.

The vibe

But even if the courts could constrain the legal declarations of emergency, the spirit of emergency seems to inflect everything that the White House does. Presidents always want to enact their agendas quickly. Trump — who argued at his first inauguration that “I alone can fix it” — has adopted a crisis footing in order to explain the suspension of normalcy. A legal finding against his tariff plan will “literally destroy the United States,” he says. And his chief policy adviser Stephen Miller declares: “The Democrat Party is not a political party. It is a domestic extremist organization.”

Trump’s emergency posture relies on interpretations of reality that would be unrecognizable to neutral people familiar with the institutions he wants to remake. Look at his arguments: Foreign aid is so woke and wasteful that we should end it altogether. The F.B.I. was so corrupted by liberal partisans that he must replace agents and refocus its police work at the true (Democratic) targets. The vaccine advisory board at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was so beholden to drug companies that its members had to be fired en masse.

The climate of emergency can be used to rationalize virtually any action. The president can pardon insurrectionists and fire the people who punished them, meaning the very idea of justice is up for grabs. The president can end civil rights enforcement, meaning landlords can discriminate on the basis of race and maybe that’s OK now, even if it’s not technically legal. The president can say that data about the economy — or weather or autism or the census — is bogus and proffer his own figures instead.

A crisis is also a surprisingly effective political cudgel. It casts Trump as the protagonist and makes his opponents play defense. Consider the National Guard deployment in Washington, D.C. “It puts the Democrats in the position of having to defend the status quo on crime,” says Whit Ayres, a Republican pollster. “And there’s nobody I know in any big city who thinks the status quo is just fine.” The politics enable Trump to expand his power dramatically. This week, the Treasury secretary told the Washington Examiner that “we may declare a national housing emergency in the fall.”

This isn’t like the most naked seizures of power in modern history, such as the Nazi takeover after the Reichstag fire in 1933. Where 20th-century autocrats often made sweeping and sudden — and illegal — moves, the autocratic playbook has changed. Now leaders don’t have to break the law, Scheppele says: “They use the law to give themselves powers that they wouldn’t otherwise have.” That’s how Orban slowly accrued strength in Hungary. He pushed a compliant legislature to alter election rules in a way that would lift his vote tally. Scheppele argues Trump is following a similar pattern.

A lasting change?

It’s not a given that all of this will work. Perhaps the Supreme Court justices will constrain Trump’s power. Most legal experts don’t believe they’ll undo birthright citizenship, for instance.

Perhaps, too, Trump’s zeal for emergencies will backfire. Voters said by wide margins that Trump’s early months were “chaotic” and “scary.” The coming years may bring fresh tumult: The Homeland Security Department, racing to recruit more immigration agents, will hire them without college degrees. Trump says armed troops may soon prowl many more cities, beginning with Chicago. It’s a tinderbox. How will voters feel if, in an accident or a misunderstanding, National Guard troops shoot civilians for protesting? Even now, the administration is struggling to secure indictments against Angelenos and Washingtonians who, it says, impeded law enforcement work.

And maybe the next time Democrats control Congress and the White House, they’ll reform emergency laws. Some legal scholars saw this moment coming after Trump’s first term and said the United States offers a president too many emergency powers. Experts at the Brennan Center for Justice, a think tank focused on the rule of law, say lawmakers should clarify that such powers sunset after 30 days if they’re not reauthorized by Congress, for instance.

But what if Trump’s government-by-emergency isn’t actually that disruptive for most Americans? An administration may suppress civil rights or radically reinterpret presidential power under the guise of addressing “emergencies” — but the majority may never notice, or care. “People can go to the bar and the restaurant in a dictatorship,” said Jason Stanley, a political philosopher at the University of Toronto, musing about what an unchecked government could do. “You can still have fun and feel free in a dictatorship.”

That’s why Trump’s opponents worry the hour is late. “If it sounds to you like I am alarmist, that is because I am ringing an alarm,” JB Pritzker, the Illinois governor, said after Trump threatened to send troops to Chicago to deal with another nonexistent crime surge. Legal experts believe the president is exploring new terrain.

Trump seems to grasp that he can acclimatize people to his style. “The line is that I’m a dictator,” Trump said last week. “But I stop crime. And a lot of people say, ‘If that’s the case, I’d rather have a dictator.’” Then he cautioned: “But I’m not a dictator.” (New York Times)

Such a nice man.

BREAKING: In an insane moment, as inflation rises, jobs plummet, and Epstein files stay hidden, Trump will sign an executive order to rename the Department of Defense as "Department of War."

— Really American 🇺🇸 (@ReallyAmerican1) September 4, 2025

So much for MAGA's "President of Peace," because priorities.pic.twitter.com/icT14i3xzO

_______________________________________________________

The US Open addresses gender inequality.

Two years ago, the trophy grew.

Crawling toward equality.

For decades, US Open women's champs got a smaller replica trophy than the men. Now they're equal.

For decades, U.S. Open women's singles champions received a replica trophy that was much smaller than the ones the men's title winners were allowed to take home.

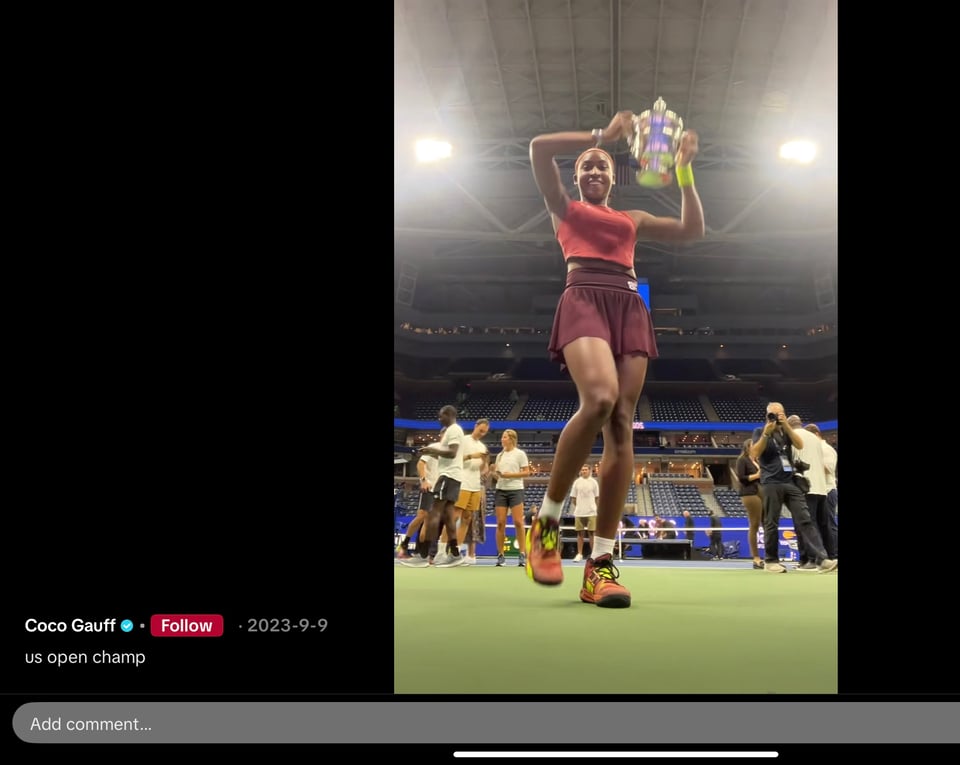

NEW YORK -- NEW YORK (AP) — Coco Gauff was surprised at how much tinier the replica trophy she got to keep after winning this year's French Open was than the trophy she posed with on court at Roland-Garros for all the world to see. She even did a TikTok about the discrepancy, drawing more than 2 million views.

Why was Gauff so taken aback by what she called the “ miniature version ”?

“I honestly did not know the size it was going to be. ... I know you never really take the original, but when I won the U.S. Open, they gave me the same size (trophy), with my name engraved on it,” Gauff told The Associated Press. “So I just assumed that Roland Garros would be the same.”

Actually, it turns out Gauff's 2023 championship at the U.S. Open marked the first time the women's singles winner in New York was given a silver cup significantly larger than the one that is used in the postmatch ceremony. Her replica hardware is 19 1/2 inches tall, the same as both the original and keepsake men's trophies — and 7 1/2 inches bigger than the original women's trophy.

US Open Coco Gauff with the replica that was equal in size to the men’s for the first time in 2023.

That one, like the original men's, is displayed during the tournament in a locked glass box near where players enter the event's main arena and will be briefly handed to, then taken away from, whoever wins the women's final in Arthur Ashe Stadium this Saturday.

From 1987, when the tradition of providing keepsakes at Flushing Meadows began, until two years ago, the female champion took home a 12-inch-tall copy. But the U.S. Tennis Association asked Tiffany & Co. to create replicas for the women to match the size of what the men are allowed to keep. That change coincided with the 50th anniversary of the tournament's 1973 move to pay equal prize money to women and men at then-player Billie Jean King's urging.

“Equality is in our DNA here at the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. Everything we do, we’re very intentional about equality ... and we wanted to do the same as it relates to the champion’s trophies,” U.S. Open tournament director Stacey Allaster said in an interview.

“We had a very robust conversation: Should we recreate a new women’s singles champion's trophy? In the end, we made the decision to stay with history and to not change the trophy itself, but to ensure that the replica trophy was of the same size as the men’s,” said Allaster, who is the chief executive of professional tennis at the USTA. “Trophies are so iconic to the history of this championships, and we just didn't feel it was the right thing to move away from that history, but ... (we wanted) to be able to award the singles champions the same sizes.”

King wasn't aware of the switch until the AP asked her about it.

“I did not know they did that. It’s fantastic. It’s equal," King said. "It sends very positive messaging that we matter just as much. Our trophy’s just as big.”

For decades, US Open women's champs got a smaller replica trophy than the men.