Friday, October 18, 2024. Annette’s News Roundup.

The world reacts to the death of Yahya Sinwar, leader of Hamas.

The Vice President’s reaction to the death of Yahya Sinwar.

Watch and listen to the vice President’s words 👇 and read the statement she had issued by the White House.

here's Kamala Harris's full statement on the killing of Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar pic.twitter.com/dlijkaM6vX

— Aaron Rupar (@atrupar) October 17, 2024

Remarks by Vice President Harris on the Death of Yahya Sinwar | The White House.

President Biden’s words on the death of Yahya Sinwar.

Emmanuel Macron.

Yahya Sinwar was the main person responsible for the terrorist attacks and barbaric acts of October 7th. Today, I think with emotion of the victims, including 48 of our compatriots, and their loved ones. France demands the release of all hostages still held by Hamas.

— Emmanuel Macron (@EmmanuelMacron) October 17, 2024

Israel’s biggest allies are reacting to the news of Yahya Sinwar’s death. Germany’s Foreign Office said that the Hamas leader had “brought death to thousands of people and immeasurable suffering across an entire region.” It called on Hamas to “immediately release all hostages and lay down its weapons,” saying that “the suffering of the people in Gaza must finally end.” (New York Times).

A Gazan reflecting on Sinwar to the NYT pic.twitter.com/2o8cLInnNZ

— Adam Rubenstein (@RubensteinAdam) October 17, 2024

One more thing.

🚨 BREAKING: President Biden just landed in Germany and upon landing called for an end to the war in Gaza. pic.twitter.com/RSWAQ2rU9B

— Chris D. Jackson (@ChrisDJackson) October 17, 2024

Tim Walz is always busy.

North Carolina.

Today in Durham, @BillClinton and I reminded North Carolinians to vote early – and to get their family, friends, and neighbors to do the same.

— Tim Walz (@Tim_Walz) October 17, 2024

We need all hands on deck to win this thing. https://t.co/uyNRZrYcpq pic.twitter.com/0rfFKfXvpQ

Yaaaasssssssssss!

— Art Candee 🍿🥤 (@ArtCandee) October 17, 2024

Chicago rapper Common showed up in North Carolina to support Tim Walz at his rally in Winston-Salem! pic.twitter.com/8DteYdDu77

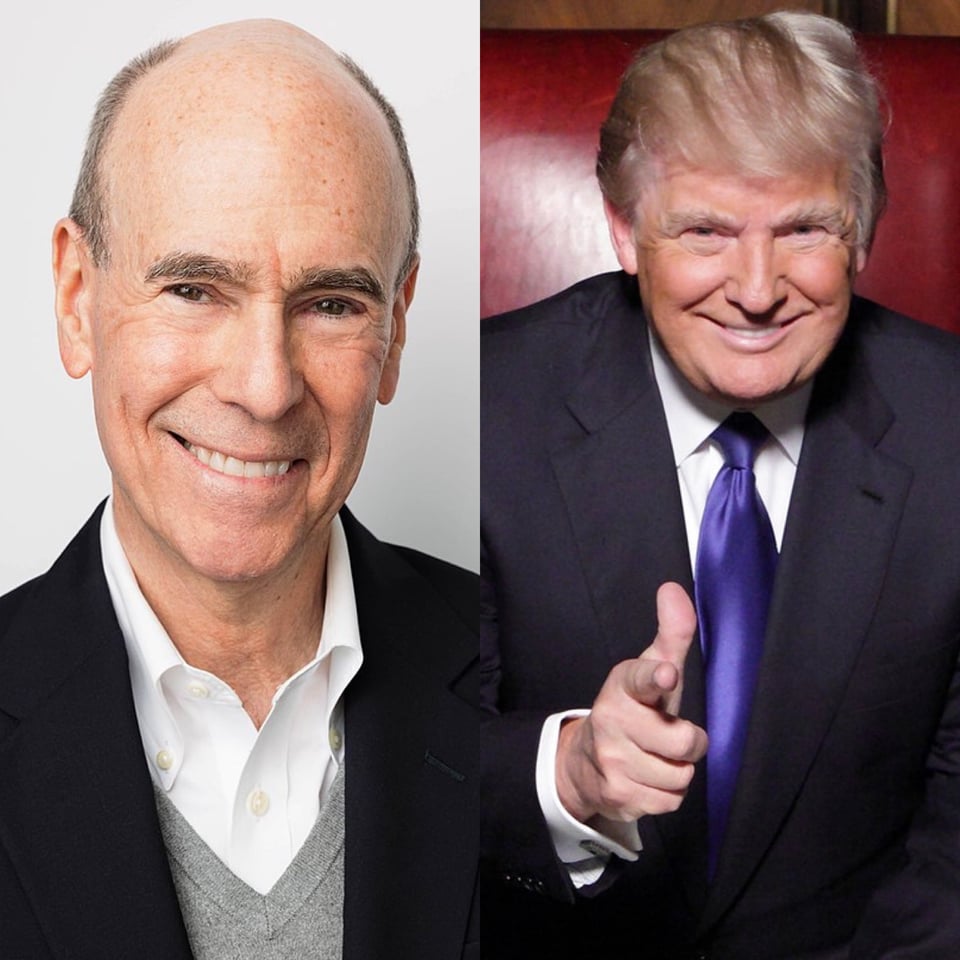

A confession from the chief marketeer of ‘The Apprentice.’

We Created a Monster: Trump Was a TV Fantasy Invented for 'The Apprentice'

NBC’s former chief marketer regrets selling an illusion that has had dire consequences for the world.

I want to apologize to America. I helped create a monster.

For nearly 25 years, I led marketing at NBC and NBCUniversal. I led the team that marketed “The Apprentice,” the reality show that made Donald Trump a household name outside of New York City, where he was better known for overextending his empire and appearing in celebrity gossip columns.

To sell the show, we created the narrative that Trump was a super-successful businessman who lived like royalty. That was the conceit of the show. At the very least, it was a substantial exaggeration; at worst, it created a false narrative by making him seem more successful than he was.

In fact, Trump declared business bankruptcy four times before the show went into production, and at least twice more during his 14 seasons hosting. The imposing board room where he famously fired contestants was a set, because his real boardroom was too old and shabby for TV.

Trump may have been the perfect choice to be the boss of this show, because more successful CEOs were too busy to get involved in reality TV and didn’t want to hire random game show winners onto their executive teams. Trump had no such concerns. He had plenty of time for filming, he loved the attention and it painted a positive picture of him that wasn’t true.

At NBC, we promoted the show relentlessly. Thousands of 30-second promo spots that spread the fantasy of Trump’s supposed business acumen were beamed over the airwaves to nearly every household in the country. The image of Trump that we promoted was highly exaggerated.

In its own way, it was “fake news” that we spread over America like a heavy snowstorm. I never imagined that the picture we painted of Trump as a successful businessman would help catapult him to the White House.

I discovered in my interactions with him over the years that he is manipulative, yet extraordinarily easy to manipulate. He has an unfillable compliment hole. No amount is too much. Flatter him and he is compliant. World leaders, including apparently Russian strongman Vladimir Putin and North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un, have discovered that too.

I also found Trump remarkably thin-skinned. He aggressively goes after those who critique him and seeks retribution. That’s not very businesslike – and it’s certainly not presidential. This week, he threatened to use the National Guard against Americans who oppose him, calling them the “enemy from within.”

I learned early on in my dealings with Trump that he thought he could simply say something over and over, and eventually people would believe it. He would say to me, “‘The Apprentice’ – America’s No. 1 TV show.” But it wasn’t. Not that week. Not that season. I had the ratings in front of me. He had seen and heard the ratings, but that didn’t matter. He just kept saying it was the “No. 1 show on television,” even after we corrected him. He repeated it on press tours too, knowing full well it was wrong. He didn’t like being fact-checked back then either.

Exaggerating ratings is one thing, but spreading falsehoods about relief work of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, about immigrants eating cats and dogs, about the deadly COVID-19 pandemic, about him winning the 2020 election or countless other lies is far more dangerous.

Now America is facing a critical choice. Should this elderly, would-be emperor with no clothes, who is well known for stretching and abandoning the truth, be president again?

I spent 50 years successfully promoting television magic, making mountains out of molehills every day. But I say now to my fellow Americans, without any promotional exaggeration: If you believe that Trump will be better for you or better for the country, that is an illusion, much like “The Apprentice” was. Even if you are a born-and-bred Republican, as I was, I strongly urge you to vote for Kamala Harris. The country will be better off and so will you.

(US News and World Report by John D. Miller who was the chief marketing officer for NBC and NBCUniversal, and retired as chair of the NBCUniversal Marketing Council.)

Copy these words and share on your social media -

From the chief marketeer of THE APPRENTICE.

“ While we were successful in marketing 'The Apprentice,' we also did irreparable harm by creating the false image of Trump as a successful leader. I deeply regret that. And I regret that it has taken me so long to go public."

“Even if you are a born-and-bred Republican, as I was, I strongly urge you to vote for Kamala Harris. The country will be better off and so will you.”

Biden-Harris cancel more student debt.

The Biden administration approves about $4.5 million in additional student loan relief for more than 60,000 borrowers, bringing the total relief under the administration to $175 billion for more than 4.8 million borrowers, the Department of Education says. https://t.co/htsRTdIl1F

— NBC News (@NBCNews) October 17, 2024

President Biden and I are making it easier for Americans to receive the student debt relief they earned through Public Service Loan Forgiveness.

— Vice President Kamala Harris (@VP) October 17, 2024

Because of our work, over one million public servants – including dedicated teachers like Brittany – have now had their debt forgiven. pic.twitter.com/fhqaW0F7HM

Adam Gopnik and Neal Katyal on what to expect if Trump wins.

They make clear on why we must fight like hell these last 18 days until November 5th.

Adam Gopnik - How Alarmed Should We Be If Trump Wins Again?

A long trip on an American highway in the summer of 2024 leaves the impression that two kinds of billboards now have near-monopoly rule over our roads. On one side, the billboards, gravely black-and-white and soberly reassuring, advertise cancer centers. (“We treat every type of cancer, including the most important one: yours”; “Beat 3 Brain Tumors. At 57, I gave birth, again.”) On the other side, brightly colored and deliberately clownish billboards advertise malpractice and personal-injury lawyers, with phone numbers emblazoned in giant type and the lawyers wearing superhero costumes or intimidating glares, staring down at the highway as they promise to do to juries.

A new Tocqueville considering the landscape would be certain that all Americans do is get sick and sue each other. We ask doctors to cure us of incurable illnesses, and we ask lawyers to take on the doctors who haven’t. We are frightened and we are angry; we look to expert intervention for the fears, and to comic but effective-seeming figures for retaliation against the experts who disappoint us.

Much of this is distinctly American—the idea that cancer-treatment centers would be in competitive relationships with one another, and so need to advertise, would be as unimaginable in any other industrialized country as the idea that the best way to adjudicate responsibility for a car accident is through aggressive lawsuits. Both reflect national beliefs: in competition, however unreal, and in the assignment of blame, however misplaced. We want to think that, if we haven’t fully enjoyed our birthright of plenty and prosperity, a nameable villain is at fault.

To grasp what is at stake in this strangest of political seasons, it helps to define the space in which the contest is taking place. We may be standing on the edge of an abyss, and yet nothing is wrong, in the expected way of countries on the brink of apocalypse. The country is not convulsed with riots, hyperinflation, or mass immiseration. What we have is a sort of phony war—a drôle de guerre, a sitzkrieg—with the vehemence of conflict mainly confined to what we might call the cultural space.

These days, everybody talks about spaces: the “gastronomic space,” the “podcast space,” even, on N.F.L. podcasts, the “analytic space.” Derived from some combination of sociology and interior design, the word has elbowed aside terms like “field” or “conversation,” perhaps because it’s even more expansive. The “space” of a national election is, for that reason, never self-evident; we’ve always searched for clues.

And so William Dean Howells began his 1860 campaign biography of Abraham Lincoln by mocking the search for a Revolutionary pedigree for Presidential candidates and situating Lincoln in the antislavery West, in contrast to the resigned and too-knowing East. North vs. South may have defined the frame of the approaching war, but Howells was prescient in identifying East vs. West as another critical electoral space. This opposition would prove crucial—first, to the war, with the triumph of the Westerner Ulysses S. Grant over the well-bred Eastern generals, and then to the rejuvenation of the Democratic Party, drawing on free-silver populism and an appeal to the values of the resource-extracting, expansionist West above those of the industrialized, centralized East.

A century later, the press thought that the big issues in the race between Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy were Quemoy and Matsu (two tiny Taiwan Strait islands, claimed by both China and Taiwan), the downed U-2, the missile gap, and other much debated Cold War obsessions. But Norman Mailer, in what may be the best thing he ever wrote, saw the space as marked by the rise of movie-star politics—the image-based contests that, from J.F.K. to Ronald Reagan, would dominate American life. In “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” published in Esquire, Mailer revealed that a campaign that looked at first glance like the usual black-and-white wire-service photography of the first half of the twentieth century was really the beginning of our Day-Glo-colored Pop-art turn.

And our own electoral space? We hear about the overlooked vs. the élite, the rural vs. the urban, the coastal vs. the flyover, the aged vs. the young—about the dispossessed vs. the beneficiaries of global neoliberalism. Upon closer examination, however, these binaries blur. Support for populist nativism doesn’t track neatly with economic disadvantage. Some of Donald Trump’s keenest supporters have boats as well as cars and are typically the wealthier citizens of poorer rural areas. His stock among billionaires remains high, and his surprising support among Gen Z males is something his campaign exploits with visits to podcasts that no non-Zoomer has ever heard of.

But polarized nations don’t actually polarize around fixed poles. Civil confrontations invariably cross classes and castes, bringing together people from radically different social cohorts while separating seemingly natural allies. The English Revolution of the seventeenth century, like the French one of the eighteenth, did not array worn-out aristocrats against an ascendant bourgeoisie or fierce-eyed sansculottes. There were, one might say, good people on both sides. Or, rather, there were individual aristocrats, merchants, and laborers choosing different sides in these prerevolutionary moments. No civil war takes place between classes; coalitions of many kinds square off against one another.

In part, that’s because there’s no straightforward way of defining our “interests.” It’s in the interest of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs to have big tax cuts; in the longer term, it’s also in their interest to have honest rule-of-law government that isn’t in thrall to guilds or patrons—to be able to float new ideas without paying baksheesh to politicians or having to worry about falling out of sixth-floor windows. “Interests” fail as an explanatory principle.

Does talk of values and ideas get us closer? A central story of American public life during the past three or four decades is (as this writer has noted) that liberals have wanted political victories while reliably securing only cultural victories, even as conservatives, wanting cultural victories, get only political ones. Right-wing Presidents and legislatures are elected, even as one barrier after another has fallen on the traditionalist front of manners and mores. Consider the widespread acceptance of same-sex marriage. A social transformation once so seemingly untenable that even Barack Obama said he was against it, in his first campaign for President, became an uncontroversial rite within scarcely more than a decade.

Right-wing political power has, over the past half century, turned out to have almost no ability to stave off progressive social change: Nixon took the White House in a landslide while Norman Lear took the airwaves in a ratings sweep. And so a kind of permanent paralysis has set in. The right has kept electing politicians who’ve said, “Enough! No more ‘Anything goes’!”—and anything has kept going. No matter how many right-wing politicians came to power, no matter how many right-wing judges were appointed, conservatives decided that the entire culture was rigged against them.

On the left, the failure of cultural power to produce political change tends to lead to a doubling down on the cultural side, so that wholesome college campuses can seem the last redoubt of Red Guard attitudes, though not, to be sure, of Red Guard authority. On the right, the failure of political power to produce cultural change tends to lead to a doubling down on the political side in a way that turns politics into cultural theatre. Having lost the actual stages, conservatives yearn to enact a show in which their adversaries are rendered humiliated and powerless, just as they have felt humiliated and powerless. When an intolerable contradiction is allowed to exist for long enough, it produces a Trump.

As much as television was the essential medium of a dozen bygone Presidential campaigns (not to mention the medium that made Trump a star), the podcast has become the essential medium of this one. For people under forty, the form—typically long-winded and shapeless—is as tangibly present as Walter Cronkite’s tightly scripted half-hour news show was fifty years ago, though the D.I.Y. nature of most podcasts, and the premium on host-read advertisements, makes for abrupt tonal changes as startling as those of the highway billboards.

On the enormously popular, liberal-minded “Pod Save America,” for instance, the hosts make no secret of their belief that the election is a test, as severe as any since the Civil War, of whether a government so conceived can long endure. Then they switch cheerfully to reading ads for Tommy John underwear (“with the supportive pouch”), for herbal hangover remedies, and for an app that promises to cancel all your excess streaming subscriptions, a peculiarly niche obsession (“I accidentally paid for Showtime twice!” “That’s bad!”). George Conway, the former Republican (and White House husband) turned leading anti-Trumper, states bleakly on his podcast for the Bulwark, the news-and-opinion site, that Trump’s whole purpose is to avoid imprisonment, a motivation that would disgrace the leader of any Third World country. Then he immediately leaps into offering—like an old-fashioned a.m.-radio host pushing Chock Full o’Nuts—testimonials for HexClad cookware, with charming self-deprecation about his own kitchen skills. How serious can the crisis be if cookware and boxers cohabit so cozily with the apocalypse?

And then there’s the galvanic space of social media. In the nineteen-seventies and eighties, we were told, by everyone from Jean Baudrillard to Daniel Boorstin, that television had reduced us to numbed observers of events no longer within our control. We had become spectators instead of citizens. In contrast, the arena of social media is that of action and engagement—and not merely engagement but enragement, with algorithms acting out addictively on tiny tablets. The aura of the Internet age is energized, passionate, and, above all, angry. The algorithms dictate regular mortar rounds of text messages that seem to come not from an eager politician but from an infuriated lover, in the manner of Glenn Close in “Fatal Attraction”: “Are you ignoring us?” “We’ve reached out to you personally!” “This is the sixth time we’ve asked you!” At one level, we know they’re entirely impersonal, while, at another, we know that politicians wouldn’t do this unless it worked, and it works because, at still another level, we are incapable of knowing what we know; it doesn’t feel entirely impersonal. You can doomscroll your way to your doom. The democratic theorists of old longed for an activated citizenry; somehow they failed to recognize how easily citizens could be activated to oppose deliberative democracy.

If the cultural advantages of liberalism have given it a more pointed politics in places where politics lacks worldly consequences, its real-world politics can seem curiously blunted. Kamala Harris, like Joe Biden before her, is an utterly normal workaday politician of the kind we used to find in any functioning democracy—bending right, bending left, placating here and postponing confrontation there, glaring here and, yes, laughing there. Demographics aside, there is nothing exceptional about Harris, which is her virtue. Yet we live in exceptional times, and liberal proceduralists and institutionalists are so committed to procedures and institutions—to laws and their reasonable interpretation, to norms and their continuation—that they can be slow to grasp that the world around them has changed.

One can only imagine the fulminations that would have ensued in 2020 had the anti-democratic injustice of the Electoral College—which effectively amplifies the political power of rural areas at the expense of the country’s richest and most productive areas—tilted in the other direction. Indeed, before the 2000 election, when it appeared as if it might, Karl Rove and the George W. Bush campaign had a plan in place to challenge the results with a “grassroots” movement designed to short-circuit the Electoral College and make the popular-vote winner prevail. No Democrat even suggests such a thing now.

It’s almost as painful to see the impunity with which Supreme Court Justices have torched their institution’s legitimacy. One Justice has the upside-down flag of the insurrectionists flying on his property; another, married to a professional election denialist, enjoys undeclared largesse from a plutocrat. There is, apparently, little to be done, nor even any familiar language of protest to draw on. Prepared by experience to believe in institutions, mainstream liberals believe in their belief even as the institutions are degraded in front of their eyes.

In one respect, the space of politics in 2024 is transoceanic. The forms of Trumpism are mirrored in other countries. In the U.K., a similar wave engendered the catastrophe of Brexit; in France, it has brought an equally extreme right-wing party to the brink, though not to the seat, of power; in Italy, it elevated Matteo Salvini to national prominence and made Giorgia Meloni Prime Minister. In Sweden, an extreme-right group is claiming voters in numbers no one would ever have thought possible, while Canadian conservatives have taken a sharp turn toward the far right.

What all these currents have in common is an obsessive fear of immigration. Fear of the other still seems to be the primary mover of collective emotion. Even when it is utterly self-destructive—as in Britain, where the xenophobia of Brexit cut the U.K. off from traditional allies while increasing immigration from the Global South—the apprehension that “we” are being flooded by frightening foreigners works its malign magic.

It’s an old but persistent delusion that far-right nationalism is not rooted in the emotional needs of far-right nationalists but arises, instead, from the injustices of neoliberalism. And so many on the left insist that all those Trump voters are really Bernie Sanders voters who just haven’t had their consciousness raised yet. In fact, a similar constellation of populist figures has emerged, sharing platforms, plans, and ideologies, in countries where neoliberalism made little impact, and where a strong system of social welfare remains in place. If a broadened welfare state—national health insurance, stronger unions, higher minimum wages, and the rest—would cure the plague in the U.S., one would expect that countries with resilient welfare states would be immune from it. They are not.

Though Trump can be situated in a transoceanic space of populism, he isn’t a mere symptom of global trends: he is a singularly dangerous character, and the product of a specific cultural milieu. To be sure, much of New York has always been hostile to him, and eager to disown him; in a 1984 profile of him in GQ, Graydon Carter made the point that Trump was the only New Yorker who ever referred to Sixth Avenue as the “Avenue of the Americas.” Yet we’re part of Trump’s identity, as was made clear by his recent rally on Long Island—pointless as a matter of swing-state campaigning, but central to his self-definition. His belligerence could come directly from the two New York tabloid heroes of his formative years in the city: John Gotti, the gangster who led the Gambino crime family, and George Steinbrenner, the owner of the Yankees. When Trump came of age, Gotti was all over the front page of the tabloids, as “the Teflon Don,” and Steinbrenner was all over the back sports pages, as “the Boss.”

Steinbrenner was legendary for his middle-of-the-night phone calls, for his temper and combativeness. Like Trump, who theatricalized the activity, he had a reputation for ruthlessly firing people. (Gotti had his own way of doing that.) Steinbrenner was famous for having no loyalty to anyone. He mocked the very players he had acquired and created an atmosphere of absolute chaos. It used to be said that Steinbrenner reduced the once proud Yankees baseball culture to that of professional wrestling, and that arena is another Trumpian space. Pro wrestling is all about having contests that aren’t really contested—that are known to be “rigged,” to use a Trumpian word—and yet evoke genuine emotion in their audience.

At the same time, Trump has mastered the gangster’s technique of accusing others of crimes he has committed. The agents listening to the Gotti wiretap were mystified when he claimed innocence of the just-committed murder of Big Paul Castellano, conjecturing, in apparent seclusion with his soldiers, about who else might have done it: “Whoever killed this cocksucker, probably the cops killed this Paul.” Denying having someone whacked even in the presence of those who were with you when you whacked him was a capo’s signature move.

Marrying the American paranoid style to the more recent cult of the image, Trump can draw on the manner of the tabloid star and show that his is a game, a show, not to be taken quite seriously while still being serious in actually inciting violent insurrections and planning to expel millions of helpless immigrants. Self-defined as a showman, he can say anything and simultaneously drain it of content, just as Gotti, knowing that he had killed Castellano, thought it credible to deny it—not within his conscience, which did not exist, but within an imaginary courtroom. Trump evidently learned that, in the realm of national politics, you could push the boundaries of publicity and tabloid invective far further than they had ever been pushed.

Trump’s ability to be both joking and severe at the same time is what gives him his power and his immunity. This power extends even to something as unprecedented as the assault on the U.S. Capitol. Trump demanded violence (“If you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore”) but stuck in three words, “peacefully and patriotically,” that, however hollow, were meant to immunize him, Gotti-style. They were, so to speak, meant for the cops on the wiretap. Trump’s resilience is not, as we would like to tell our children about resilience, a function of his character. It’s a function of his not having one.

Just as Trump’s support cuts across the usual divisions, so, too, does a divide among his opponents—between the maximizers, who think that Trump is a unique threat to liberal democracy, and the minimizers, who think that he is merely the kind of clown a democracy is bound to throw up from time to time. The minimizers (who can be found among both Marxist Jacobin contributors and Never Trump National Review conservatives) will say that Trump has crossed the wires of culture and politics in a way that opportunistically responds to the previous paralysis, but that this merely places him in an American tradition. Democracy depends on the idea that the socially unacceptable might become acceptable. Andrew Jackson campaigned on similar themes with a similar manner—and was every bit as ignorant and every bit as unaware as Trump. (And his campaigns of slaughter against Indigenous people really were genocidal.) Trump’s politics may be ugly, foolish, and vain, but ours is often an ugly, undereducated, and vain country. Democracy is meant to be a mirror; it shows what it shows.

Indeed, America’s recent history has shown that politics is a trailing indicator of cultural change, and that one generation’s most vulgar entertainment becomes the next generation’s accepted style of political argument. David S. Reynolds, in his biography of Lincoln, reflects on how the new urban love of weird spectacle in the mid-nineteenth century was something Lincoln welcomed. P. T. Barnum’s genius lay in taking circus grotesques and making them exemplary Americans: the tiny General Tom Thumb was a hero, not a freak. Lincoln saw that it cost him nothing to be an American spectacle in a climate of sensation; he even hosted a reception at the White House for Tom Thumb and his wife—as much a violation of the decorum of the Founding Fathers as Trump’s investment in Hulk Hogan at the Republican Convention. Lincoln understood the Barnum side of American life, just as Trump understands its W.W.E. side.

And so, the minimizers say, taking Trump seriously as a threat to democracy in America is like taking Roman Reigns seriously as a threat to fair play in sports. Trump is an entertainer. The only thing he really wants are ratings. When opposing abortion was necessary to his electoral coalition, he opposed it—but then, when that was creating ratings trouble in other households, he sent signals that he wasn’t exactly opposed to it. When Project 2025, which he vaguely set in motion and claims never to have read, threatened his ratings, he repudiated it. The one continuity is his thirst for popularity, which is, in a sense, our own. He rows furiously away from any threatening waterfall back to the center of the river—including on Obamacare. And, the minimizers say, in the end, he did leave the White House peacefully, if gracelessly.

In any case, the panic is hardly unique to Trump. Reagan, too, was vilified and feared in his day, seen as the reductio ad absurdum of the culture of the image, an automaton projecting his controllers’ authoritarian impulses. Nixon was the subject of a savage satire by Philip Roth that ended with him running against the Devil for the Presidency of Hell. The minimizers tell us that liberals overreact in real time, write revisionist history when it’s over, and never see the difference between their stories.

The maximizers regard the minimizers’ case as wishful thinking buoyed up by surreptitious resentments, a refusal to concede anything to those we hate even if it means accepting someone we despise. Maximizers who call Trump a fascist are dismissed by the minimizers as either engaging in name-calling or forcing a facile parallel. Yet the parallel isn’t meant to be historically absolute; it is meant to be, as it were, oncologically acute. A freckle is not the same as a melanoma; nor is a Stage I melanoma the same as the Stage IV kind. But a skilled reader of lesions can sense which is which and predict the potential course if untreated. Trumpism is a cancerous phenomenon. Treated with surgery once, it now threatens to come back in a more aggressive form, subject neither to the radiation of “guardrails” nor to the chemo of “constraints.” It may well rage out of control and kill its host.

And so the maximalist case is made up not of alarmist fantasies, then, but of dulled diagnostic fact, duly registered. Think hard about the probable consequences of a second Trump Administration—about the things he has promised to do and can do, the things that the hard-core group of rancidly discontented figures (as usual with authoritarians, more committed than he is to an ideology) who surround him wants him to do and can do. Having lost the popular vote, as he surely will, he will not speak up to reconcile “all Americans.” He will insist that he won the popular vote, and by a landslide. He will pardon and then celebrate the January 6th insurrectionists, and thereby guarantee the existence of a paramilitary organization that’s capable of committing violence on his behalf without fear of consequences. He will, with an obedient Attorney General, begin prosecuting his political opponents; he was largely unsuccessful in his previous attempt only because the heads of two U.S. Attorneys’ offices, who are no longer there, refused to coöperate. When he begins to pressure CNN and ABC, and they, with all the vulnerabilities of large corporations, bend to his will, telling themselves that his is now the will of the people, what will we do to fend off the slow degradation of open debate?

Trump will certainly abandon Ukraine to Vladimir Putin and realign this country with dictatorships and against nato and the democratic alliance of Europe. Above all, the spirit of vengeful reprisal is the totality of his beliefs—very much like the fascists of the twentieth century in being a man and a movement without any positive doctrine except revenge against his imagined enemies. And against this: What? Who? The spirit of resistance may prove too frail, and too exhausted, to rise again to the contest. Who can have confidence that a democracy could endure such a figure in absolute control and survive? An oncologist who, in the face of this much evidence, shrugged and proposed watchful waiting as the best therapy would not be an optimist. He would be guilty of gross malpractice. One of those personal-injury lawyers on the billboards would sue him, and win.

What any plausible explanation must confront is the fact that Trump is a distinctively vile human being and a spectacularly malignant political actor. In fables and fiction, in every Disney cartoon and Batman movie, we have no trouble recognizing and understanding the villains. They are embittered, canny, ludicrous in some ways and shrewd in others, their lives governed by envy and resentment, often rooted in the acts of people who’ve slighted them. (“They’ll never laugh at me again!”) They nonetheless have considerable charm and the ability to attract a cult following. This is Ursula, Hades, Scar—to go no further than the Disney canon. Extend it, if that seems too childlike, to the realms of Edmund in “King Lear” and Richard III: smart people, all, almost lovable in their self-recognition of their deviousness, but not people we ever want to see in power, for in power their imaginations become unimaginably deadly. Villains in fables are rarely grounded in any cause larger than their own grievances—they hate Snow White for being beautiful, resent Hercules for being strong and virtuous. Bane is blowing up Gotham because he feels misused, not because he truly has a better city in mind.

Trump is a villain. He would be a cartoon villain, if only this were a cartoon. Every time you try to give him a break—to grasp his charisma, historicize his ascent, sympathize with his admirers—the sinister truth asserts itself and can’t be squashed down. He will tell another lie so preposterous, or malign another shared decency so absolutely, or threaten violence so plausibly, or just engage in behavior so unhinged and hate-filled that you’ll recoil and rebound to your original terror at his return to power. One outrage succeeds another until we become exhausted and have to work hard even to remember the outrages of a few weeks past: the helicopter ride that never happened (but whose storytelling purpose was to demean Kamala Harris as a woman), or the cemetery visit that ended in a grotesque thumbs-up by a graveside (and whose symbolic purpose was to cynically enlist grieving parents on behalf of his contempt). No matter how deranged his behavior is, though, it does not seem to alter his good fortune.

Villainy inheres in individuals. There is certainly a far-right political space alive in the developed world, but none of its inhabitants—not Marine Le Pen or Giorgia Meloni or even Viktor Orbán—are remotely as reckless or as crazy as Trump. Our self-soothing habit of imagining that what has not yet happened cannot happen is the space in which Trump lives, just as comically deranged as he seems and still more dangerous than we know.

Nothing is ever entirely new, and the space between actual events and their disassociated representation is part of modernity. We live in that disassociated space. Generations of cultural critics have warned that we are lost in a labyrinth and cannot tell real things from illusion. Yet the familiar passage from peril to parody now happens almost simultaneously. Events remain piercingly actual and threatening in their effects on real people, while also being duplicated in a fictive system that shows and spoofs them at the same time. One side of the highway is all cancer; the other side all crazy. Their confoundment is our confusion.

It is telling that the most successful entertainments of our age are the dark comic-book movies—the Batman films and the X-Men and the Avengers and the rest of those cinematic universes. This cultural leviathan was launched by the discovery that these ridiculous comic-book figures, generations old, could now land only if treated seriously, with sombre backstories and true stakes. Our heroes tend to dullness; our villains, garishly painted monsters from the id, are the ones who fuel the franchise.

During the debate last month in Philadelphia, as Trump’s madness rose to a peak of raging lunacy—“They’re eating the dogs”; “He hates her!”—ABC, in its commercial breaks, cut to ads for “Joker: Folie à Deux,” the new Joaquin Phoenix movie, in which the crazed villain swirls and grins. It is a Gotham gone mad, and a Gotham, against all the settled rules of fable-making, without a Batman to come to the rescue. Shuttling between the comic-book villain and the grimacing, red-faced, and unhinged man who may be reëlected President in a few weeks, one struggled to distinguish our culture’s most extravagant imagination of derangement from the real thing. The space is that strange, and the stakes that high. (The New Yorker).

Neal Katyal - In Case of an Election Crisis, This Is What You Need to Know.

In 2020, when Donald Trump questioned the results of the election, the courts decisively rejected his efforts, over and over again. In 2024, the judicial branch may be unable to save our democracy.

The rogues are no longer amateurs. They have spent the last four years going pro, meticulously devising a strategy across multiple fronts — state legislatures, Congress, executive branches and elected judges — to overturn any close election.

The new challenges will take place in forums that have increasingly purged officials who put country over party. They may take place against the backdrop of razor-thin election margins in key swing states, meaning that any successful challenge could change the election.

We have just a few short weeks to understand these challenges so that we can be vigilant about them.

First, in the courts, dozens of suits have already been filed. Litigation in Pennsylvania has begun over whether undated mail-in ballots are permissible and whether provisional ballots can be allowed. Stephen Miller, a former Trump adviser, has brought suit in Arizona claiming that judges should be able to throw out election results.

Many states recently changed how they conduct voting. Even a minor modification could tee up legal challenges, and some affirmatively invite chaos.

Any time a state changes an election rule or can be accused of not having followed one, someone with legal standing (like a resident of that state or a candidate or a party) can bring a lawsuit. Recently courts in Georgia and Pennsylvania protected voting rights, but these lower court decisions may be appealed within the state system.

Lawsuits will also make their way to federal courts. Federal judges have on occasion been known to act in political ways, and any one of the 1,200 of them could make a decision that plunges the nation into deep confusion. In regular times, the judicial system corrects for outlier judges through the appeals process, up to, if necessary, the U.S. Supreme Court. But here we are looking at a narrow window of time, and public confidence in the court is nearly at a three-decade low. No matter how nonpartisan the justices are, should the Supreme Court intervene, there is a high chance millions of Americans would see the decision as unfair.

Second, state officials and local election boards also can wreak havoc by refusing to certify elections, and this time they will have new tools to manufacture justifications for undermining democracy. A new Georgia law empowering local boards to investigate voter fraud offers a prime example. On its face, the law sounds laudatory or at least innocuous. But the law could be read to give an election board the power to cherry-pick an instance or two, claim the entire election illegitimate and refuse to certify the votes. This is straight out of the 2020 playbook, when Mr. Trump reportedly successfully pressured two Wayne County, Mich., election officials not to certify the 2020 vote totals. Fortunately, that tactic didn’t work. This year it might.

In 2022, Congress passed the Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Improvement Act, which tried to reduce the risk by stating that, unless the state designates another official in advance, the governor of a state, not a local board, must certify electors. But the governor may be in on the fix, too, or give in to a pressure campaign.

Third, there are state legislatures to contend with: They might make baseless allegations of fraud and interfere to get a different slate of electors appointed to the Electoral College, as happened in 2020. Last year, in Moore v. Harper, the Supreme Court put an end to many such tactics. (Disclosure: I argued the case in front of the court.) But a state legislature might ignore the law and try anyway, especially if the governor of that state is politically aligned and seizes on the alternative slate.

Fourth, the Congress has the power to swing the entire election. The rules are complex; even as a law professor, I can barely make sense of them.

The good news is that under the 2022 law, Congress has reduced the chance of mischief. The threshold for a member of Congress to object to the vote from any state is higher. It must be signed by at least 20 percent of the members of both houses for it to be taken up and perhaps debated and voted on. To pass, an objection must be sustained by a simple majority in both chambers. Only two categories of objections are permissible: if the vote of any electors was not “regularly given” or if the electors were not “lawfully certified.”

The bad news is that the rules are so complicated that they could be stretched, wrongly, to give Congress the power to select the next president by sustaining bogus objections. Don’t get me wrong: Such maneuvering is totally inconsistent with the 2022 law. But it can be attempted and create chaos. Likewise, if a governor certifies a fake slate, that will be hard for Congress to fix.

Before 2020, most Americans had no reason to fear this problem. Political parties largely acted in good faith, and most understood that our basic democratic norms were sacrosanct. In a world in which one party is still consumed by election fraud claims from 2020 (as JD Vance’s nonanswer in the debate underscored) and is prepared to claim the same in 2024, we have much to fear.

It does not require much imagination to see a member of Congress acting in bad faith to try to squeeze through bogus election fraud theories and plunge the country into uncertainty on Jan. 6. The 20 percent voting threshold is meant to avoid crackpot election fraud theories, but these days more than 20 percent of Congress might be inclined to support a crackpot theory. And some Republican strategists are gearing up to argue the 2022 Electoral Count Reform Act is unconstitutional and invalid.

Here’s yet another wrinkle: If no candidate gets a majority of the Electoral College, either through mischief or a simple tie, then the Constitution sends the election to Congress. Mischief can occur on Jan. 6, for example, with Congress knocking votes of electors as not being “regularly given.” If for whatever reason no candidate gets a majority of electoral votes, the House will decide the presidency, under arcane voting rules in which the states, not a House majority, pick the president.

The stark reality is that there are no immediate solutions to a potential election crisis. The personnel to trigger one — in the courts, legislatures and executive branches — are largely in place.

Two votes on Nov. 5 will matter tremendously to sidestepping the chaos. One is the presidential vote. If either candidate wins the Electoral College decisively, any dispute will be rendered academic.

The other is the vote for Congress. A key point here is that it is the new House and Senate, not the existing ones, that will call the shots on Jan. 6. Congress desperately needs principled people who will put democracy over self-interest and party politics.

Americans should vote for candidates who share a commitment to democracy and who will think critically before accepting election innuendo. The next month must be about ensuring continued rule by the people and for the people. ( Op-ed, New York Times).

Billie Jean King and 100 Athletes celebrate the 50th anniversary of her Women’s Sports Foundation.

Billie Jean King and her wife Ilana Kloss at the Women’s Sports Foundation gala in 2024.

NEW YORK (AP) — Billie Jean King started the Women’s Sports Foundation with a $5,000 check.

She’s turned that investment into $100 million and a half century of helping girls and women achieve their dreams through travel and training grants, local sports programs and mentoring athletes and coaches.

King celebrated the 50th anniversary of the foundation by honoring the 1999 U.S. women’s World Cup champions, PWHL and Los Angeles Dodgers co-owner Mark Walter and the 2024 WNBA rookie class on Wednesday night in New York.

“What makes me happy is creating opportunities and dreams for others,” King told The Associated Press in a recent interview. “I look back and that’s what drives me.”

Nearly 100 female athletes attended the awards dinner to celebrate the milestone and King, a tireless advocate for equal pay and more investment in women’s sports.

That includes awards host and soccer honoree Julie Foudy. She graduated from Stanford and played for the 1999 U.S. soccer team that won the World Cup before a record crowd of more than 90,000 at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California.

“She’s remained a friend and mentor and such a catalyst for changing the trajectory of women’s soccer and so many sports,” said Foudy, a former president of the Women’s Sports Foundation and current soccer broadcaster for Turner and TNT.

After the World Cup win, Foudy and the team turned to King, Donna Lopiano and Donna de Verona for advice about improving pay and starting a professional soccer league.

“I’ll never forget, (King) said ‘What are you guys doing about it?’” said Foudy, regarding their collective leverage with the U.S. Soccer Federation. “And as players, that was the exact epiphany we needed at that moment.”

Foudy and the ’99ers eventually witnessed the successful struggle toward equity, helping lay the foundation for the current U.S. women’s national team to receive the same pay and working conditions as the men’s team. A players’ lawsuit against the federation resulted in a landmark $24 million settlement in 2022.

“Billie doesn’t have just one meeting. She’d check in and follow up and ask ‘What do you need?’” Foudy said. “She was at that first (WUSA professional) game in Washington D.C. (in 2001) and was a big proponent of the importance of having a league and player pool for the longevity and growth of women’s soccer.”

The current iteration is the NWSL, which started in 2013 and now has 14 teams. Foudy is part of the ownership group of Angel City FC. New owners Bob Iger and Willow Bay acquired a controlling stake in the team in July, with a value of $250 million.

King recently joined forces with Mark and Kimbra Walter to create the Professional Women’s Hockey League (PWHL), which will launch its second season in late November. U.S. Olympic gold medalist Kendall Coyne Schofield reached out to King to help unify the fractured pro hockey landscape into one viable league. King, who is part of the Dodgers’ ownership group, collaborated with Walter to form the new six-team league.

The WNBA rookie class, led by No. 1 pick Caitlin Clark, received the Next Gen Award for “showing up, showing out and boldly carrying the torch forward.” The popularity of Indiana’s Clark and Chicago’s Angel Reese generated unprecedented WNBA attendance, more nationally televised games and record-breaking TV ratings this summer.

“Caitlin Clark is fantastic,” King said. “It reminds me of Chris Evert in 1971, when she changed everything at the U.S Open. Anytime a player can do well, she helps everybody.”

The rookie class includes Cameron Brink (Stanford), Kamilla Cardoso (NCAA champion South Carolina), Rickea Jackson (Tennessee), Jacy Sheldon (Ohio State), Aaliyah Edwards (UConn), Reese (LSU) and Alissa Pili (Utah).

The WNBA lags in pay equity, with Clark receiving only $76,000 in her rookie season compared to the NBA No. 1 pick, who gets $12 million. WNBA players may see an increase in salary in 2026 from a new 11-year media rights deal for approximately $200 million a year ahead of the next collective bargaining agreement. The players’ union is interested in increasing the WNBA revenue share from 9.3%. NBA players receive about 50% of the money generated from TV deals, ticket sales, merchandise and licensing.

King says it may take more time to close the pay gaps because women’s sports is “still in its infancy.”

“The NBA is 78 years old, the WNBA is 28 years old,” King said. “(Former NBA Commissioner) David Stern made a huge difference, he was a marketing genius. We need to continue to do that for women’s sports.”

King and the ‘Original Nine’ helped market the early women’s professional tennis circuit, and she formed the WTA with players a week before Wimbledon in 1973. She advocated for Title IX, beat Bobby Riggs and fought for equal prize money in tennis. In between, she won 39 Grand Slam titles during her career.

The next milestone for the 80-year-old King will be receiving the Congressional Gold Medal. It’s one of the highest U.S. civilian honors for individuals whose achievements have a lasting impact on their field.

“The Women’s Sports Foundation, nobody knew how long it would last,” she said. “I look at the 50th anniversary as a continuation to create more opportunities. You can’t let up.” (Associated Press).

Trump is always crazy.

Donald Trump has peddled harmful conspiracies about immigrant communities eating pets and spread misinformation about resources available to those impacted by Hurricanes Milton and Helene.

— Kamala Harris (@KamalaHarris) October 17, 2024

He is a deeply unserious man—but the consequences of him having power are deadly serious. pic.twitter.com/EESw5XYk8c

"Are you serious? A day of love? A day of love when more than 140 officers were injured, people lost their career, people lost their lives? Democracy was in shambles because of what he did, because he refused to concede." https://t.co/B59laAHspa

— Ryan J. Reilly (@ryanjreilly) October 17, 2024

It’s amazing how the New York Times keeps coming up with euphemisms to avoid saying Trump is lying, Today Trump is “inverting the facts.” pic.twitter.com/IrCbVs0FwT

— Mark Jacob (@MarkJacob16) October 17, 2024

Have you wondered if Tucker Carlson works for Putin? Canada’s Prime Minister knows he is.

The Prime Minister of Canada says under oath that RT, which the U.S. State Department alleges is engaged in "information operations, covert influence, and military procurement," is funding Jordan Peterson and Tucker Carlson. https://t.co/9mYUmCFBfI

— Michael Weiss (@michaeldweiss) October 17, 2024

Your Daily Reminder.

Trump is a convicted felon.

On May 30th, he was found guilty on 34 felony counts by the unanimous vote of 12 ordinary citizens.

The Convicted Felon Donald J. Trump was scheduled to be sentenced on July 11th and September 18th. He will now be sentenced on November 26.

“…January 6th was a day of LOVE”

— Jon Lion Fine Art 🌈🇺🇸🦅 (@jonlionfineart2) October 17, 2024

-Donald Trump, Convicted Felon

My *edited* drawing: pic.twitter.com/tfwwo5wn6I

For fun.

A former President in North Carolina.

Bill Clinton: I'm too old to gild a lily. Heck, I'm only two months younger than Donald Trump. But the good news for you is I will not spend 30 minutes swaying back and forth to music. pic.twitter.com/EbkjKVJJGa

— Aaron Rupar (@atrupar) October 17, 2024

The Vice President in Wisconsin yesterday.

Kamala Harris: Oh, you guys are at the wrong rally. I think you meant to go to the smaller one down the street pic.twitter.com/tjhbDB9m3R

— Acyn (@Acyn) October 17, 2024

This 👇 promises a different kind of fun.

BREAKING: Judge Chutkan has denied Trump's effort to block a new dossier of Jack Smith's evidence from becoming public.

She said she will unseal it today.