Friday, August 22, 2025. Annette’s Roundup for Democracy.

** Special announcement ** - this ** Roundup ** is very long. The first article from the New Yorker is a detailed accounting of Trump’s grifting and thievery. I think it is the longest post I have ever published. If you are interested in the numbers, I am sure you will be fascinated.

The rest of the ** Roundup ** is more topical, on the subjects of the day - gerrymandering wars, and other daily happenings. Your email carrier may require you to react to read the whole of it. I hope you do, and find it all worth your time.

See you on Tuesday.

How much is Trump pocketing off the Presidency?

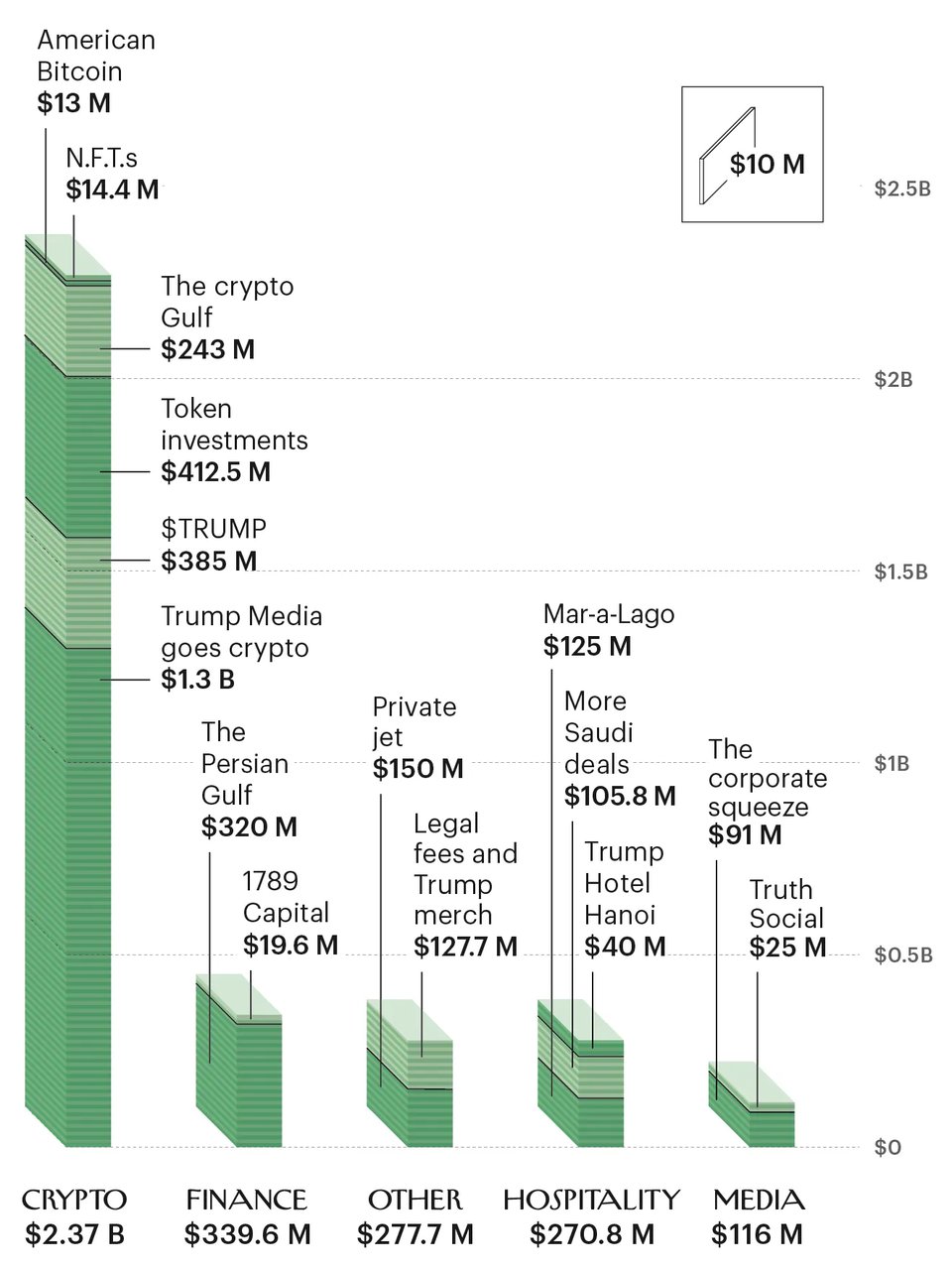

The New Yorker staff writer David D. Kirkpatrick tallies up the Trump family’s profiteering, including Mar-a-Lago memberships, five Persian Gulf mega-projects, a luxury jet from Qatar, a sprawling resort in Hanoi, half a dozen projects peddling crypto, and MAGA merch.

At a press conference on January 11, 2017, President-elect Donald Trump explained for the first time how he would handle the many conflicts of interest that his business empire posed for his new role. His company, the Trump Organization, collected money from all over the world for luxury condos, hotel rentals, development projects, and club memberships, and he had made deals that put his name on everything from mail-order steaks to get-rich-quick courses. Could citizens trust him to put the common good ahead of personal profit? How would he assure Americans that payments to his business weren’t doubling as payoffs?

A journalist asked Trump if he would release his tax returns, as Presidents had done for decades. Trump said no, and then explained just how unconstrained he felt by such conventions. He’d recently learned that the President, being beholden only to the voters, is subject to none of the regulations that restrict subordinate officials from conducting private business on the side. He called the loophole “a no-conflict-of-interest provision,” as if it were a perk of his employment contract.

To illustrate just how glaring a conflict the law allowed him, Trump volunteered that, during the transition, he’d entertained a two-billion-dollar offer “to do a deal in Dubai.” The offer had come from Hussain Sajwani, an Emirati real-estate tycoon with close ties to his country’s rulers. Trump emphasized that he “didn’t have to turn it down.” Nevertheless, he’d passed, because he didn’t “want to take advantage of something”; he disliked “the way that looks.” Therefore, he continued, his eldest sons, Donald, Jr., and Eric, would assume daily management of his businesses until he left office.

Trump then turned things over to Sheri Dillon, one of his tax lawyers, who argued that he could hardly be expected to do more than the temporary handover. Trump would not “destroy the company he built.” Since Trump’s star turn on the NBC reality show “The Apprentice,” the Trump Organization had mainly sold the use of his name. Most of its profits came from developers who flew the Trump flag over buildings that he didn’t build or own, or from businesses that used his name to sell shirts, mattresses, or pizza. If Trump tried to off-load his whole company, Dillon explained, a buyer might overpay in order “to curry favor with the President,” or, just as worrisome, might demean the highest office in the land by crassly cashing in on the President’s name. Trump and his family, Dillon declared, would never do anything that might “be perceived to be exploitive of the office of the Presidency.”

That was a different era. Dillon’s firm stopped representing Trump in 2021, after the mob he stirred up attacked the U.S. Capitol. And in Trump’s second term the President and his family have paid no mind to their lawyer’s promise. During Trump’s first term, they pledged to abstain from any new deals overseas. That’s out the window. The Trumps are now cashing in on five major deals in the Persian Gulf alone. Donald, Jr., on a recent visit to Qatar, said that the family’s restraint during the first Trump Administration had not stopped his father’s critics from constantly accusing the family of “profiteering.” So the Trumps would no longer lock themselves in “a proverbial padded room, because it almost doesn’t matter—they’re going to hit you no matter what.” (A spokeswoman for the Trump Organization told me that it employs an outside ethics adviser—currently, Karina Lynch, a lawyer and a lobbyist who previously worked as a Republican Senate staffer and has represented Donald, Jr.—to “avoid even the appearance of impropriety.”)

Many payments now flowing to Trump, his wife, and his children and their spouses would be unimaginable without his Presidencies: a two-billion-dollar investment from a fund controlled by the Saudi crown prince; a luxury jet from the Emir of Qatar; profits from at least five different ventures peddling crypto; fees from an exclusive club stocked with Cabinet officials and named Executive Branch. Fred Wertheimer, the dean of ethics-reform advocates, told me that, “when it comes to using his public office to amass personal profits, Trump is a unicorn—no one else even comes close.” Yet the public has largely shrugged. In a recent article for the Times, Peter Baker, a White House correspondent, wrote that the Trumps “have done more to monetize the presidency than anyone who has ever occupied the White House.” But Baker noted that the brazenness of the Trump family’s “moneymaking schemes” appears to have made such transactions seem almost normal.

How much money does it all amount to? What’s the number? In March, Forbes, known for ranking the wealth of billionaires, estimated that Trump’s net worth had more than doubled in the previous year, surpassing five billion dollars. In July, the Times put Trump’s wealth at upward of ten billion. Yet both estimates included billions of dollars in paper profits that would almost certainly disintegrate if the Trumps pulled out of certain investments. (What’s Truth Social worth without him?) These estimates also included assets untainted by any obvious exploitation of the Presidency, such as properties that Trump owned before entering office, or fees paid by resort customers who simply want to play golf or book a hotel room.

Although the notion that Trump is making colossal sums off the Presidency has become commonplace, nobody could tell me how much he’s made. Norm Eisen, a government-ethics lawyer and a vocal Trump critic, said, “We don’t know the full amounts.” Robert Weissman, a co-president of the left-leaning advocacy group Public Citizen, said, “We will never really know.” Wertheimer noted that for decades Trump had boasted constantly, and in detail, about how rich he was. “He doesn’t talk about it anymore,” Wertheimer said. “He may be the greatest con artist in American history.”

A more considered accounting seemed in order. I decided to attempt to tally up just how much Trump and his immediate family have pocketed off his time in the White House.

In financial terms, the Presidency came to Trump at a fortuitous moment. Russ Buettner and Susanne Craig, the Times reporters who obtained some of Trump’s tax returns, conclude in their book, “Lucky Loser,” that by 2015 he had burned through much of the vast fortune passed on to him by his self-made father—an inheritance worth as much as half a billion dollars today. If Trump had put that money into the stock market, he could have ended up much richer. His life style also guzzled money. In 1990, in a deal to keep the Trump Organization out of bankruptcy, his lenders agreed that he needed four hundred and fifty thousand dollars a month just to make ends meet.

“The Apprentice,” on which he played the outsized version of himself that he has always tried to project to the world, once covered his losses. In the seven years following its début, in 2004, the show paid him $135.2 million. And its glamorizing effect allowed him to make money without buying or building anything, just by licensing his name and selling endorsements. Nearly all the real-estate projects he announced during this period—from Hawaii to Israel—were licensing deals. Licensing and endorsements made him $103.2 million in riskless profit. “I don’t want to say it was free revenue,” Donald, Jr., later testified in a New York court. But he did allow that the company’s licensing business was “a pretty spectacular system.”

Yet even the “Apprentice” windfall wasn’t always enough to keep Trump in the black. According to annual reports that the Trumps sent their lenders from 2011 to 2017, during those years Trump brought in $259 million from television and licensing contracts, but, thanks to his habit of overspending on properties, he still reported a negative cash flow of $46.8 million. Dwindling viewership numbers had killed “The Apprentice” in 2010, and by 2015 its doubly gimmicky offspring, “The Celebrity Apprentice,” was ailing, too. Trump’s licensing, endorsement, and “Apprentice” income fell to $22 million that year. Buettner and Craig note that between 2014 and 2016 Trump sold about $220 million in stock—nearly all his stock holdings—apparently to make up for losses as that income tapered off. Then, on June 16, 2015, Trump launched his first Presidential campaign with a speech in which he described Mexican immigrants as criminals and “rapists.” NBC kicked him off the air. Macy’s, Serta, and Phillips-Van Heusen ended endorsement deals.

After Trump won the election, lawsuits filed in the backlash against his Presidency added some big new expenses. By the start of his second term, he owed nearly five hundred million dollars to New York State, which had sued him for fraud, and more than $88 million to E. Jean Carroll, who had sued him for sexual assault and defamation. (Appeals are still pending.) Trump, in short, was in a tight spot when he first entered the White House and in an even tighter one when he returned. Just six months later, his financial situation has vastly improved.

Trump’s critics often describe his Administration as an oligarchy or a kleptocracy, conjuring parallels with Vladimir Putin. Yet experts who track international corruption told me that this is going too far. Global titans of self-dealing—such as Najib Razik, Malaysia’s former Prime Minister—divert vast sums from national coffers directly into their bank accounts. U.S. prosecutors have charged that Razik stole about four and a half billion dollars, including by transferring about seven hundred million into his personal accounts. Nobody has credibly accused Trump of simply embezzling payments to the I.R.S. Gary Kalman, the executive director at the U.S. branch of the corruption watchdog Transparency International, cautioned against “making stuff up just because everything is believable.”

Critics of Trump’s “oligarchy” invariably point to his relationship with Elon Musk. Musk contributed more than $290 million to back Trump and other Republicans in 2024. Trump then gave him an Administration role with seemingly extralegal power to reorder federal agencies; all the while, Musk’s businesses Tesla, SpaceX, and Starlink were profiting from government contracts or subsidies. In March, the President performed in what was effectively a television commercial on the White House lawn. Trump, after announcing that he would purchase a red Tesla parked there, declared, “It’s a great product—as good as it gets.” All that may be unseemly. Yet every American political campaign relies on private donations. All modern Presidents have sold access for campaign money, and all have rewarded donors with political appointments—especially ambassadorships.

More important, campaign-finance laws restrict how Trump can use his political war chest. Since reëntering the White House, Trump has raised the record-breaking sum of six hundred million dollars for his political operation. He can tap into that reserve to attack congressional enemies, and he can direct it toward other campaigns. (Donald, Jr., has contemplated a Presidential run.) Yet the money generally can’t bankroll personal expenses. In the campaign-money game, Trump plays at an Olympian level, but he hasn’t changed the rules.

Personal self-enrichment is where Trump is a true innovator, and his winnings in that category are also harder to quantify. On his tax returns, Trump has aggressively minimized the value of his assets and maximized the extent of his losses. On loan applications, he’s done the opposite, puffing up his wealth to borrow as much as possible. And on the financial-disclosure forms he’s been required to file as a candidate or as President, he usually provides only a business’s gross revenue, not its bottom line, thus reporting tens of millions of dollars in “income” from hotels that are actually losing money.

Bruce Dubinsky, a forensic accountant who testified in the fraud trial of Bernie Madoff and investigated the collapse of Lehman Brothers as a part of its bankruptcy, closely followed Trump’s New York fraud trial. Dubinsky told me that the opaque ownership structure of the Trump businesses makes it difficult to assess changes in his net worth. It’s similarly hard to isolate his Presidential profits, in part because estimating how much his businesses might have made if he weren’t President would require detailed comparisons with similar enterprises that have non-Presidential owners. By way of example, Dubinsky, who lives in Florida, noted that he’d recently visited the Trump golf course in Jupiter, “just to play golf.” He added, “So how much value to assign to his status as President is a daunting task.”

That blurriness is why ethics experts say that any outside business can pose a conflict of interest and may open a conduit for bribery. But, propriety aside, I was after a fair, dispassionate quantification of the Trumps’ profits from two Presidencies. Mar-a-Lago, the for-profit club that has become the maga mecca and the weekend White House, was an obvious place to start.

MAR-A-LAGO

In 2016, Trump, while running for President, was also suing a restaurateur for cutting ties over his bigoted comments about Mexican immigrants. In a deposition that summer, Trump testified that the Presidential race had so far had no “huge impact” on his hotel and resort businesses, which were “fairly steady.” One exception, he said, was Mar-a-Lago, the Palm Beach estate he’d turned into a private club after acquiring it, in 1985, for roughly ten million dollars. As though surprised by a happy accident, Trump testified that, according to the club’s manager, the campaign had given Mar-a-Lago “the best year we’ve ever had.”

If many Presidents have traded access for campaign donations, only Trump has run a business selling an open-ended opportunity to mingle with him and his circle. In addition to the revenue he generated by holding his own campaign events at his club, he has profited from other candidates, conservative groups, and influence seekers rushing to hold events there, too. The club says that it limits membership to five hundred people; each reportedly pays an annual fee of about twenty thousand dollars. But after the 2016 election Trump began jacking up the initiation fee. In 2016, it was a hundred thousand dollars; last fall, it was set to rise to a million.

Trump’s financial-disclosure forms indicate that since 2014 Mar-a-Lago’s annual revenue has jumped from ten million dollars to fifty million. At the same time, Forbes reported, operating costs have been stable, ranging from twelve million to sixteen million dollars a year. Adding it all up, I calculated that Trump’s Presidencies have brought him at least $125 million in extra profits from Mar-a-Lago.

Estimated gain: $125 million

LEGAL FEES AND TRUMP MERCH

Although candidates cannot pocket campaign contributions, no President has ever tried as hard as Trump to siphon off at least some of that money. According to the nonprofit OpenSecrets, in the past decade Trump’s campaigns have spent more than twenty million dollars at his own hotels and resorts, contributing to Mar-a-Lago’s spike in profits. But how much, if any, of this money reached his personal accounts is impossible to guess.

Trump’s 2016 and 2024 campaign operations paid him a total of eighteen million dollars for the use of his own Boeing 757—the so-called Trump Force One. (Air Force One ferried him around during the 2020 campaign, as is standard for a sitting President.) But Barack Obama, in 2008, and Mitt Romney, in 2012, each spent a comparable sum to charter campaign planes.

Trump, however, is the first Presidential candidate to run a private online store that competes against his own campaign in selling campaign-style merch, effectively diverting his supporters’ money into his own pocket. It’s as if a fashion designer had set up a table in front of a department store to sell knockoffs of his own company’s products, at the expense of its shareholders. Among the Trump Store’s wares: a red “Gulf of America” baseball hat (fifty dollars), a pair of Trump beer koozies (eighteen dollars), and Trump flip-flops (forty dollars). Buyers might well believe that such purchases fund the maga cause or its candidates, yet Trump’s financial-disclosure forms indicate that he has made more than seventeen million dollars in income from such sales. At those prices—with negligible marketing expenses, thanks to his role as head of state—that income is surely almost all profit. Trump’s most recent disclosure form also listed licensing income of $1.1 million from a Trump guitar, $2.8 million from Trump watches, $2.5 million from “sneakers and fragrances,” $3 million from an illustrated book called “Save America,” and $1.3 million from a “God Bless the USA” Bible. That adds up to at least $27.7 million from faux campaign paraphernalia.

A political campaign fund cannot pay a candidate’s personal legal bills. But Trump found a loophole: a campaign fund can be converted into a political-action committee, and the looser restrictions on a pac allow the use of donor funds to pay such expenses. Through his pacs, Trump has spent more than a hundred million dollars of his supporters’ contributions to defend himself against an array of charges: that he defamed E. Jean Carroll while denying her account of his sexual assault, that he fraudulently hid a payoff to a porn star during the 2016 campaign, that he conspired to overturn the results of the 2020 election, and that he stole and hid classified documents after leaving the White House. Unless all those charges are part of a vast deep-state conspiracy, relieving Trump of the bills looks like a hundred-million-dollar gift for personal expenses.

Estimated gain: $127.7 million

Running total: $252.7 million

THE D.C. HOTEL

During the President’s first term, no business figured more prominently in Democratic allegations of corruption than did the Trump International Hotel in Washington. Zach Everson, who wrote an online newsletter about the scene there, told me that the hotel was “the epicenter of the swamp.” Foreign leaders booked blocks of rooms. Industry trade groups held conventions. Lobbyists, lawmakers, and Cabinet officials crowded the bar. Trump often visited; staff told Everson that tips suffered because guests stayed at their tables to gawk until the President left. If you wanted to curry his favor, where else in Washington would you stay? In 2018, when T-Mobile was seeking regulatory approval to acquire Sprint, John Legere, then T-Mobile’s chief executive, was spotted there. In ten months, he and other company executives spent nearly two hundred thousand dollars at the hotel; Legere denied any scheme to influence the White House and said he was a “longtime Trump-hotel stayer.” (The merger was approved.)

All this patronage surely flattered Trump’s ego, but it never fattened his wallet. The hotel lost money each year of his first term—a total of more than seventy million dollars. Industry executives familiar with the hotel’s operations told me that Trump’s Presidency repelled as many potential customers as it attracted. Many foreign leaders, lobbyists, and executives who might otherwise have paid handsomely for the Trump hotel’s location and luxury stayed elsewhere, fearing entanglement in an influence scandal. (T-Mobile’s Legere endured a grilling on Capitol Hill about his choice of accommodations.) In the two years after Trump’s election, hotels in Toronto, New York, Rio de Janeiro, and Panama City that had licensed the Trump name ditched it, presumably in part because it was driving away business. A Hawaii hotel followed suit in 2023.

Trump had agreed in 2012 to pay the federal government at least three million dollars a year for a long-term lease of the D.C. building, a former post-office headquarters, and to invest at least two hundred million in renovations. The hotel opened in 2016, and Trump sold it in 2022 for $375 million. Craig and Buettner, after reviewing his tax returns, conclude that he roughly broke even. Hilton Hotels took over the management, under its Waldorf Astoria brand, and people familiar with its operations said that its financial performance has improved markedly.

During Trump’s first term, Trump Turnberry, his golf resort in Scotland, also drew allegations of improper Presidential self-enrichment, because the U.S. military sometimes paid to put up service members there during overnight stops at the nearby Prestwick Airport. During the twenty-three months ending in July, 2019, the Pentagon spent at least a hundred and eighty-four thousand dollars at Trump Turnberry (at a discounted nightly room rate averaging $189.04).

Yet that property, too, lost money all four years of the first Trump Administration. It finally entered the black in 2022. And U.S. service members continued to stay there under President Joe Biden. An Air Force spokesman told me that there had been “no change” in the military’s use of the facility: “Aircrews are allowed to select the Trump Turnberry Resort, along with other hotel options in the area, if the lodging meets specific criteria of availability, suitability, expense, and proximity.”

Spending at Trump’s hotels by government agencies and influence seekers looked to me like a wash.

Estimated gain: $0

Running total: $252.7 million

THE PERSIAN GULF

The Persian Gulf has posed a unique commercial opportunity and ethical challenge for the first Commander-in-Chief who’s also a real-estate salesman. The Gulf’s Arab monarchs play complementary double roles: each is both a head of state and a major buyer of U.S. real estate and other assets. The Gulf royals put money in the very kinds of properties and investments that Trump’s family sells. In a recent interview with Tucker Carlson, Steve Witkoff, Trump’s Middle East envoy and a fellow real-estate mogul, expressed delight that the mind-set of Gulf rulers facilitates dealmaking: “Everybody’s a business guy there!” But these business guys were deeply entangled with the Trump crowd. Trump, Witkoff, and others in the two Trump Administrations—including Jared Kushner, the husband of Trump’s daughter Ivanka—had sold or tried to sell assets to the Gulf’s ruling families before entering government. And both sides can expect to do business again once Trump leaves office.

Unlike heads of state in, say, Western Europe, the Gulf monarchs wield extraordinary power over the businesses of their subjects. A Gulf monarch controls the fossil-fuel revenue that ultimately drives every enterprise in his country, from the lowliest shawarma stand to the finest resort. And he is unconstrained by independent courts or Western-style laws that might protect private interests. The richer a Gulf tycoon, the more he must depend on his sovereign’s good will. So a deal with a private firm is sometimes not much different from a deal with a ruler.

During the 2016 Republican primaries, Trump boasted of having sold condos to Saudis: “They buy apartments from me. They spend forty million, fifty million. Am I supposed to dislike them? I like them very much.” Nevertheless, he’d struggled to make licensing deals in the Gulf. The few developers outside North America willing to pay for the use of his family name were mostly building condominiums in lower-rent parts of the developing world. He’d made hundreds of thousands of dollars a year licensing his name for a two-tower project in Istanbul. (On his three most recent annual disclosure forms, he reported receiving $489,182, $392,360, and $288,061. Reporting periods can be irregular.) He’d also licensed his name for four apartment towers in India, six in South Korea, one in the Philippines, and another in Uruguay. (Resorts or other planned ventures in Georgia, Azerbaijan, and elsewhere fell through after he was elected.) Trump’s only beachhead in the Gulf was a deal with Hussain Sajwani, the tycoon close to Emirati rulers. In 2013, Sajwani, the self-styled “Donald of Dubai,” had agreed to pay the Trump Organization to manage a Trump-branded golf course, surrounded by villas, in Dubai.

When Trump was running for President in 2016, at least one emissary from the campaign suggested to the Emirati rulers that Trump’s deal with Sajwani gave them an in. Tom Barrack, Trump’s friend and informal adviser, wrote in an e-mail to the Emirati Ambassador, Yousef Al Otaiba, that Trump “has joint ventures in the U.A.E.!”

Barrack prompted the U.A.E. to begin courting Kushner, Trump’s incoming Middle East adviser, and this effort appeared to pay off stunningly. Through Kushner, the Emiratis helped persuade Trump to travel to the Persian Gulf for his first Presidential trip abroad. They also helped get Trump to support their preferred heir to the Saudi throne, Mohammed bin Salman, now the crown prince and de-facto ruler, instead of a royal cousin who’d long been the American favorite. Most remarkably, in 2017 Trump supported the U.A.E. and Saudi Arabia in a feud with neighboring Qatar. The Emiratis and the Saudis had accused their regional rival of supporting Islamist movements, and organized a blockade designed to starve the country. Qatar is a Pentagon partner, largely funding an American airbase west of Doha, and Trump’s stance contradicted the positions of his Secretaries of State and Defense. (The Saudis and the Emiratis patched things up with Qatar at the end of Trump’s first term; he and the rulers involved now act like the blockade never happened.)

Had the payments for the Dubai golf course helped the Emiratis win Trump’s favor? Would a deal with the Trump Organization have protected Qatar? A senior official of a Gulf state told me that the region’s rulers now view business with Trump “as a kind of safeguard.”

It did not take long after Trump’s first term for his family to return to the Gulf. He had left the White House in disgrace following the January 6, 2021, assault on the U.S. Capitol, but the scandal didn’t dislodge him from his position as a political kingmaker. Kevin McCarthy, the House Republican leader, had to make a pilgrimage to Mar-a-Lago to atone for declaring that Trump must accept responsibility for instigating the riot. Yet Trump and his family were now liberated from the duties of public office, and freer than ever to cash in on his status as the once and future President.

Kushner went first. During Trump’s first term, he’d quietly backed Mohammed bin Salman during the prince’s consolidation of power in Riyadh, even pushing Trump to stand by him after Saudi agents murdered Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist and a Virginia resident. Shortly after leaving the White House, Kushner asked the Saudi sovereign wealth fund to invest two billion dollars with a private-equity firm that he was founding, Affinity Partners.

The Saudi fund’s panel of investment advisers unanimously objected. Kushner had worked almost exclusively in real estate and never in private equity, and he was asking the Saudis to put up a vast sum when no American had invested a penny. The panel called the management fee that Kushner wanted—1.25 per cent of the firm’s assets, or $25 million, each year—“excessive,” given his lack of relevant experience. The advisers also worried about a “public relations” problem: the deal might look like a payoff.

The Saudi fund’s board, controlled by the crown prince, ignored the advice. Two billion dollars it was. Emirati and Qatari investors soon kicked in hundreds of millions more. Terry Gou, the Taiwanese businessman and politician who founded the manufacturing giant Foxconn and maintains close ties to China’s leaders, also invested. (While in the White House, Kushner helped arrange subsidies for a Foxconn factory in Wisconsin.) And in 2024, as Trump was poised to retake the Presidency, Kushner’s firm raised an additional $1.5 billion from the Qataris and Emiratis, bringing its assets under management to $4.8 billion.

If all the investors besides the Saudis pay the industry-standard management fee of two per cent a year, Affinity’s annual revenue comes to $81 million. Under conventional private-equity terms, Kushner’s firm, after repaying management fees, can keep an additional twenty per cent of any returns on its investments (although Kushner agreed to share some of that with the Saudis). That cut of the profits is typically the biggest windfall for a private-equity firm, and reports indicate that at least some of Kushner’s early investments, including in an Israeli financial firm and a German fitness company, are paying off. But even if Kushner fails utterly—a renewable-energy lender that his fund invested in, Solar Mosaic, recently filed for bankruptcy, in part because of Trump policy changes—Affinity still stands to take in $810 million over ten years, a typical life span for such a fund.

Congressional Democrats have asked if Kushner might be selling influence as part of the deal. Since leaving the Trump Administration, Kushner has described himself as an informal foreign-policy adviser to his father-in-law and to members of Congress. He’s also reportedly conversed with the Saudi crown prince about such foreign-policy matters as relations with Israel, and at a conference last year he said that, thanks to his White House experience, he and his firm could “do things on the geopolitical side, on the connections side.”

Last fall, Senator Ron Wyden, of Oregon, and Representative Jamie Raskin, of Maryland, unsuccessfully urged the Biden Administration’s Department of Justice to appoint a special counsel to investigate whether Kushner was illegally acting as an unregistered foreign agent. In a public letter, Wyden and Raskin argued that “the Saudi government’s decision to engage Affinity for investment advice” appeared to be “a fig leaf for funneling money directly to Mr. Kushner and his wife, Ivanka Trump,” possibly “to curry favor” or “reward them for favorable U.S. policy towards Saudi Arabia during the first Trump administration.” (Kushner called the letter a political stunt, and has argued that critical coverage of the Saudi deal only helps his firm. Although journalists “think they’re writing a bad thing,” he told Forbes, businesspeople who read those articles discover “that I’m very trusted by my partners.”)

Affinity’s fees, of course, must cover overhead, from staff compensation to office space. But Kushner is the founder and sole owner, and it’s unimaginable that the firm could have reaped such sums from those investors without his father-in-law’s Presidencies. We might conservatively assume that he personally keeps between half and two-thirds of Affinity’s fees over ten years. (He will make far more if the fund turns a profit.) Half would be $405 million. On Wall Street, the “present value” of that stream of future income—taking into account the cost of delay—is about $320 million.

Kushner also has real-estate projects in the works that pose additional conflicts of interest for Trump. A partnership with the Serbian government (backed by an Emirati investor) to build a Trump-branded hotel in Belgrade has been derailed by the discovery that its approval was based on a document that a Serbian official allegedly forged. But in January the Albanian government preliminarily approved a partnership with Kushner to build a hundred-and-eleven-acre resort on one of the few undeveloped islands in the Mediterranean. The project is said to entail a $1.4-billion investment. Still, both are real-estate developments—Kushner’s area of expertise. Unlike with the Saudi investment, it’s unfair to attribute those deals entirely to Trump’s public office, and it’s premature to guess what Kushner or his investors in the projects might someday earn. It is safest to say only that his private-equity firm has added at least $320 million to the family’s Presidential profits.

Estimated gain: $320 million

Running total: $572.7 million

MORE SAUDI DEALS

Trump’s first business with the Saudis upon leaving the White House involved golf. After the Capitol riot, the P.G.A. of America cancelled a contract to hold its televised championship the next year at his course in Bedminster, New Jersey, depriving Trump of valuable publicity. Fortunately for him, Saudi Arabia was launching its own pro-golf association, liv, and it agreed to hold a televised tournament at Bedminster. (The next year, liv announced a “framework agreement” to merge with the P.G.A. Tour; the deal hasn’t yet closed.)

But holding the liv tournament at Bedminster may have made sense for both parties even if Trump had never been President. Trump has said that he got only “peanuts” from liv, and that’s normal: clubs host such events mainly for publicity. The Saudis, for their part, secured access to a nice golf course at a time when many wouldn’t welcome them, given their human-rights record and liv’s rivalry with the P.G.A. Tour. This alliance of pariahs may have drawn Trump and the Saudis closer together, but it’s hard to say that he benefitted more than they did. And not much money changed hands.

The Trump Organization has recently signed or completed some deals to license the President’s name for real-estate projects that extended the company’s “Apprentice”-era business model. Before the President took office in 2017, a businessman and politician in Indonesia had licensed the Trump name for two golf projects. One opened in 2025; the other is still in the works. A longtime Trump Organization partner in India is adding six Trump residential projects to the four that predated Trump’s election. Indians evidently wanted to live in Trump towers even when he was just a fading reality-television star.

A recent rush of Saudi investments in Trump-branded real estate in the Gulf, however, would be hard to fathom without the Trump Presidencies. By 2020, with Trump’s image tarnished by his tumultuous political career, many developers saw less economic value in his name than they once had. The number of international developers paying to license his name had fallen to five, down from eleven before he ran for President.

But in November, 2022, Trump, after becoming the presumptive Republican Presidential nominee, announced an anomalous new deal. Dar Al Arkan, a Saudi real-estate company, had agreed to pay the Trump Organization to manage both a Trump hotel and a Trump golf course at a vast cliffside development in Muscat, Oman. In addition, Trump would likely get a cut from sales of villas surrounding the course. (The Sultan of Oman is also a partner.) The project, when completed, will be the Trump Organization’s first hotel-management deal overseas. Small-scale managers like the Trump Organization—which currently runs just eight hotels—can typically land only ten-year contracts. But the Oman project reportedly made a three-decade commitment. Developers tend to grant such terms to behemoths like Hilton or Marriott, whose scale enables them to lower costs and attract customers in ways that the Trumps never could.

In the months after Trump’s reëlection, Donald, Jr., and Eric signed a blitz of licensing deals with the same Saudi company, for major projects in Riyadh, Jeddah, Dubai, and Doha. Given that the family has acknowledged trying for decades to plant the Trump flag in the Gulf, these mega-deals are inconceivable without Trump’s Presidency.

How much are they all paying? After the pandemic, the financial performance of the Dubai golf course stabilized. Trump reported on his last three annual disclosure forms that managing the course paid him $1,283,889, $1,109,950, and $1,078,967. He now stands to make at least a million dollars a year as long as Sajwani renews the management contract—and Sajwani would be foolish to cancel while Trump is President. I estimated that Trump, by the end of his second term, will have made more than nine million dollars from managing that course.

Golf-industry experts say that, in effect, the Trump Organization merely oversees the local operations of the club and probably keeps more than eighty per cent of those fees as profit. That would net Trump about $7.2 million. In addition, the licensing fees from the Dubai golf course which Trump reported on his last three disclosure forms totalled $9.7 million; much of this money likely comes from his cut of sales of condos around the course. Such fees are usually almost all profit.

Trump’s new Gulf deals are even more lucrative. Although the Oman project isn’t scheduled to open until 2028, Trump has reported on his three most recent annual disclosure forms a total of $8.8 million in licensing income from it; this presumably includes a cut of villa presales.

He will also manage new golf courses in Muscat, Riyadh, and Doha; extrapolating from the one in Dubai, these three could bring in more than $24 million in profit in their first ten years. (Present value: $19 million.) Moreover, Trump’s name will hang on four other new condo or villa projects, in Riyadh, Jeddah, Dubai, and Doha. Taking the average of his licensing fees from the similar projects in Dubai and Muscat, we might estimate that each one brings in nine million dollars in profit in the first three years of sales—for a total of $36 million. (He recently reported five million dollars in licensing fees just a few months after announcing the Dar Al Arkan project in Dubai, suggesting even higher profits.)

Another prize will be the management and licensing fees from planned hotels at the projects in Dubai and Muscat. Because the Trumps had never managed an overseas hotel before, I looked at the income from a Trump-branded hotel in Honolulu. Before its owners took down his name, it typically brought him about two million dollars a year in licensing and management fees, according to his financial-disclosure forms. Assuming thirty-year deals at both Gulf hotels and extrapolating from the Hawaiian model, managing the two hotels for the full term might bring in $120 million in fees.

To break out Trump’s bottom line, I spoke to Dan Wasiolek, a hospitality analyst at Morningstar, an investment-research firm. (He has been willing to speak publicly about the Trump Organization’s finances; many prefer to avoid the President’s wrath.) Wasiolek told me that a typical profit margin on hotel-management fees is about sixty-five per cent. That would net Trump $78 million (present value: $42 million)—but he’ll probably make much more, because some of that is all-profit licensing income. In all, the Gulf projects that the Trump Organization has signed since 2022 are worth at least $105.8 million.

Estimated gain: $105.8 million

Running total: $678.5 million

THE PRIVATE JET

In May, the President returned from formal state visits to Saudi Arabia, the U.A.E., and Qatar with his most unusual deal so far, one without any pretense of a sale. He announced that the Emir of Qatar had agreed to make a “free gift” of a royal Boeing 747-8 for Trump’s use as a flashy Presidential jet. Trump characterized the transfer as a boon for American taxpayers: the Air Force would retain ownership of the plane until he left office. Yet Trump also said that the Pentagon would then pass the jet to his Presidential-library foundation. This “free gift” looked enough like a personal favor that the Emir has requested a memorandum of understanding confirming that it’s a donation from one government to another, in order to protect him from allegations of bribery. He also wants it in writing that Qatar didn’t propose the handover, and made it only at the President’s request. (A Qatari official told me that negotiations are ongoing.)

In the end, Trump may never get to enjoy it. Upgrading the plane to meet Presidential-security requirements could cost more than a billion dollars, which would normally require appropriation by Congress, and the work might not be finished before Trump leaves office. Still, on May 21st, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth announced that he’d accepted the jet.

The Qataris bought the plane from Boeing thirteen years ago. Its list price was $367 million. The Times reported that it might sell on the used-jet market for a hundred and fifty million. Karoline Leavitt, the White House press secretary, told me in an e-mail that “any gift given by a foreign government is always accepted in full compliance with all applicable laws.” But it’s risible to suggest that the jet would have been offered to any President but Trump. Perhaps the Gulf rulers see such transactions as a form of insurance—a way to avoid the kind of hardship that befell Qatar during Trump’s first Administration. The payments may also have bought good will. Trump, standing near Mohammed bin Salman on the recent trip to Saudi Arabia, unexpectedly announced that he would end sanctions against Syria—currently led by a former Al Qaeda fighter who is trying to prove that he has reformed. “Oh, what I do for the crown prince,” Trump reflected aloud. During his first term, Trump had disappointed the Arab Gulf rulers by declining to retaliate against their regional nemesis, Iran, after an attack on the Saudi oil-processing facility at Abqaiq. In June, when Trump ordered air strikes on Iran, the Arab monarchs surely cheered.

Estimated gain: $150 million

Running total: $828.5 million

TRUMP HOTEL HANOI

In September, 2024, with polls forecasting Trump’s likely return to office, Tô Lâm, the General Secretary of Vietnam’s ruling Communist Party, visited New York and dispatched a Central Committee member to wrap up a Trump resort deal. The Central Committee member oversaw the signing of an agreement between the Party committee of Hung Yen Province and a consortium of investors arranged by the Trump Organization. The same day, Trump took time away from the campaign to join Eric in signing an agreement with a Vietnamese company, known for its office parks, that will build the property and pay the Trumps for the use of their name. The planned development, with a projected cost of $1.5 billion, will include a hotel, residences, and fifty-four holes of golf, occupying an area three times the size of Central Park. It appears to be the largest Trump-branded development in the world.

Trump’s past levies on imports from China spurred businesses to shift operations to Vietnam, and exports to the U.S. now account for about a third of Vietnam’s economy. Trump’s protectionist tariffs therefore pose both a threat and an opportunity to Vietnam, giving it a singular incentive to cultivate his good will.

Perhaps with that in mind, Vietnamese authorities have expedited the resort project, overriding local laws and procedures. In a letter obtained by the Times, Vietnamese officials said that they were accelerating the project because it is “receiving special attention from the Trump Administration and President Donald Trump personally.”

Would this deal have happened in this form if Trump had retired to Mar-a-Lago in 2021? Unlikely. On his most recent financial-disclosure form, Trump reported five million dollars in initial income from licensing his name to the project, which is expected to open in 2027. The development’s huge scale and the unique character of the Vietnamese market make projecting profits difficult. Even if the deal extends for just ten years and the Trump Organization makes only as much each year as it did in the first few months, that will be fifty million dollars. (Present value: $40 million.) Judging from other Trump licensing deals, the actual profits will likely be higher.

In July, Trump said that he had reached a provisional trade agreement with Vietnam. He had been threatening a forty-six-per-cent tariff, but he said that the new deal lowered that to twenty per cent. The Vietnamese, contradicting him, have insisted that they are negotiating for an even lower rate.

Estimated gain: $40 million

Running total: $868.5 million

Chart by Francesco Muzzi.

THE CORPORATE SQUEEZE

In a 2016 law-review article, Susan Seager, a First Amendment lawyer and a professor at the University of California, Irvine School of Law, described Trump as a “libel loser.” In the past five decades, he has lost or withdrawn a dozen suits against media companies, and failed to follow through on many other threats. The handful of claims that he filed after leaving the White House all seemed certain to end similarly. Last spring, for example, he sued ABC News for defamation because its anchor George Stephanopoulos said that a court had found Trump “liable for rape.” The court had found Trump liable for sexually abusing and defaming E. Jean Carroll, and the judge had emphasized that Carroll had not failed to prove “that Mr. Trump ‘raped’ her as many people commonly understand the word.” To win his lawsuit, Trump would have to prove that Stephanopoulos spoke with “actual malice”—a seemingly insurmountable burden.

But after the election ABC News, a unit of Disney, abruptly settled the case. Confronting a plaintiff who now held enormous sway over its future regulation, Disney agreed to pay fifteen million dollars to Trump’s Presidential-library foundation—the same nonprofit that will presumably take ownership of the Qatari jet.

Trump also sued Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram. After January 6, 2021, Meta, having concluded that he’d used its platforms to incite violence, suspended his accounts. His suit’s tenuous claim was that Meta had somehow violated his First Amendment rights by yielding to pressure from Democratic officials. Yet, a month after ABC’s payment, Meta settled, too, paying $22 million to Trump’s “library.” Then X, formerly known as Twitter and now owned by Elon Musk, reportedly paid about ten million dollars to settle a similar suit. (X has not said whether the company is paying the nonprofit or Trump himself.) In July, CBS News, a unit of Paramount, agreed to pay the nonprofit sixteen million dollars to settle a lawsuit over which snippets of an interview with Kamala Harris it had chosen to broadcast.

Media-law experts considered all of Trump’s recent claims ridiculous. Trump appears to be the first sitting President or Presidential nominee in American history to sue for libel or defamation. Such contests could never be fair—a sitting President holds too much power over any defendant. “None of these companies would have settled if Trump weren’t President and wielding power over mergers and regulations and government contracts,” Seager said. Yet most of the settlements, like the Qatari jet, were paid to Trump’s foundation. Should they count as personal profits?

Twenty-five years ago, President Bill Clinton endured an epic scandal related to a much smaller contribution to a similar nonprofit. Denise Rich, a Democratic donor, gave four hundred and fifty thousand dollars to his Presidential-library foundation, and Clinton, on his final day in office, pardoned her ex-husband, Marc Rich, a tax dodger and a sanctions evader who’d fled to Switzerland. Presidents George W. Bush, Obama, and Biden followed stricter procedures to avoid any appearance of selling a pardon, even for campaign donations. Trump has had no such qualms. The Times reported that he pardoned Paul Walczak, another wealthy tax evader, shortly after Walczak’s mother paid a million dollars to attend a Trump fund-raiser. Walczak’s pardon application reportedly cited his mother’s contributions to Trump and to other Republicans.

The Walczak payments, though, were political funds, which politicians cannot use as personal piggy banks. Presidential-library foundations have far fewer restrictions. The board of the Trump-library foundation consists of one of his lawyers, one of his sons, and one of his sons-in-law. The foundation needs only to adhere to the purpose stated in its articles of incorporation: “To preserve and steward the legacy of President Donald J. Trump.” Harvey P. Dale, who heads the N.Y.U. School of Law’s National Center on Philanthropy and the Law, told me that Trump’s foundation couldn’t simply transfer its money to Trump or his sons. But it could feasibly pay for Trump to travel the world. It might even be able to pay him directly, as an adviser. (After all, who knows better how to steward his legacy?) Trevor Potter, the president of the nonprofit Campaign Legal Center and a Republican former chairman of the F.E.C., told me that Trump’s foundation “will constitute an additional account that the former President will control and can use to benefit his post-Presidential life style.” That’s why I counted the Qatari jet as personal profit. The same applies to the settlement payments.

With another media giant, Amazon, the Trumps worked more directly. In December, over dinner at Mar-a-Lago, Melania Trump pitched Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s chairman, on a documentary that she hoped to produce about her return to the White House. The competition for the rights was flaccid: the Wall Street Journal reported that Disney had offered fourteen million dollars; Netflix and Apple had declined to bid. But Amazon agreed to pay forty million dollars. Of course, former Presidents and their wives routinely earn gigantic advances for memoirs. Yet First Couples have customarily waited until they’ve left office to open those auctions, avoiding the appearance that they might be selling influence. Amazon’s data-center business and Bezos’s Blue Origin space-travel company both receive billions of dollars in government contracts. Melania Trump’s cut of Amazon’s payment is reportedly about $28 million.

Estimated gain: $91 million

Running total: $959.5 million

TRUTH SOCIAL

In October, 2021, Trump announced a plan to launch his own social-media platform, Truth Social. The social-media market was crowded. Yet Trump, who had formed a shell company for the platform, said that he had already agreed to a lucrative merger. His shell company was combining with Digital World Acquisition Corp., a financial contrivance called a special-purpose acquisition company. spacs, a Wall Street fad at the time, are also known as blank-check companies. A spac’s sponsor raises capital through an initial public offering of shares in an empty vessel that operates no business at all. The offering sells only a pledge that the spac will use its funding to buy some enticing enterprise. Digital World, headed by a Miami financier friendly with Trump, had raised $293 million, and it agreed to put that money into a merger with the Truth Social shell. The combined company, now called Trump Media & Technology Group, then handed Trump a roughly sixty-per-cent stake and named him its chairman. His share of the $293 million was equivalent to $175 million. (In a press release, Trump Media projected that, on the stock market, the combined company would be worth $1.7 billion, making the President’s stake worth more than a billion dollars.)

In retrospect, this chain of promises looks like a watershed moment in Trump’s evolution from builder to entertainer to pitchman to political entrepreneur. At each stage, he has hawked products that are harder and harder to measure or touch.

Any money that the President makes from Trump Media unquestionably depends on his status as the former and current Commander-in-Chief. The company’s customer base is the maga movement. And Trump releases news-making Presidential statements exclusively through Truth Social, exploiting his public position to draw attention to his private platform. But how much of that apparent $175 million Trump might pocket is a trickier question. Trump Media’s market value has gyrated with its share price, ranging from as high as six billion dollars to as low as $1.6 billion.

Trump Media lost more than four hundred million dollars last year, and in each of the past four quarters the company has brought in only about a million dollars or less in revenue. It has never shared a convincing plan for making Truth Social profitable. Institutional investors call it a meme stock; that is, Trump Media’s share price fluctuates with small investors’ feelings about Trump, regardless of any underlying value. If Trump tried to cash out, he’d undoubtedly set off a stampede that would trample the stock’s price before he could make off with much.

This past spring, I asked Dubinsky, the forensic accountant, to estimate how much Truth Social had added to Trump’s wealth. Applying metrics used to evaluate other social-media companies, such as daily users (it has about four hundred thousand), Dubinsky put the value of Trump’s stake at between four million and twenty million dollars. Though he considered twenty million “very generous,” to be charitable he suggested adding another five million, putting Trump’s stake at about $25 million. He commented, “I personally would never invest in it.” (In response to detailed questions, Trump Media & Technology Group declined to answer and threatened to sue.)

Estimated gain: $25 million

Running total: $984.5 million

1789 CAPITAL

On January 31st, Ned’s Club, a chain of luxury social clubs with locations in London, New York, and Doha, opened an outpost near the White House. Ned’s is owned by the investor Ronald Burkle, a Democratic donor, who is also the chairman and majority shareholder in Soho House, a kind of sister company. The Washington Ned’s is a joint venture with Michael Milken, the financier who was convicted in 1990 of securities fraud and pardoned in 2020 by Trump. Kellyanne Conway, the former Trump adviser, sits on the club’s membership committee. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, and former Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin have reportedly been seen there.

Regular members pay a five-thousand-dollar entry fee plus five thousand dollars a year; élite members can pay as much as a hundred and twenty five thousand dollars up front and twenty-five thousand a year for access to all Ned’s and Soho House locations. The D.C. Ned’s, which occupies the top three stories of a historic building, has a leafy roof deck overlooking the Mall, three restaurants, and a capacious library that serves cocktails at night.

In April, Donald, Jr., circulated plans for a rival club, Executive Branch, which would initially cap its membership at two hundred people, and charge an initiation fee of up to half a million dollars. A person involved in the club told me that twenty “founding members” paid the half-million-dollar fee; regular members paid closer to a hundred thousand. Donald, Jr., formed the club with his friend Omeed Malik, who is a financier, a Trump donor, and a Mar-a-Lago member; Zack and Alex Witkoff, the sons of President Trump’s old friend and current diplomatic envoy Steve Witkoff; and Christopher Buskirk, a conservative writer who is also a Malik associate. Malik told the Washington Post that friends from the 2024 Trump campaign “wanted to be able to catch up when our paths crossed in D.C.,” adding that Executive Branch’s founders sought an “experience comparable to the finest social clubs in the world.” He said that its élite members don’t need to pay for access because they are “already plugged in.” He called the club’s name “tongue in cheek.”

How do Donald, Jr., and his partners plan to compete against Ned’s? Malik, in addition to offering a maga-friendly atmosphere, has promised to bar journalists and lobbyists. (An exception was made for Jeff Miller, a lobbyist who is a friend of the founders and paid half a million.) The person involved also said that Executive Branch has recruited a renowned chef and a team from Carriage House, a club in Palm Beach. Malik told the Washington Post that the club will provide multiple lounge areas and a mezzanine V.I.P. section, creating the atmosphere of an elegant mansion. The New York Post reported that Executive Branch had spent ten million dollars on art. Yet it’s hard to imagine all that opulence in the venue that the partners have leased: a reported nine-thousand-square-foot subterranean space beneath an unexceptional condominium on a busy avenue in Georgetown, next to a TJ Maxx and an office of the Department of Motor Vehicles. Until March, the space housed a series of bars that struggled to keep out underage drinkers.

Executive Branch held a soft opening for founders in June, and then closed again for the summer, to make final renovations. Perhaps the new club has pulled off an interior-design miracle. Even so, its biggest draw is surely the offer of intimacy with the President’s family and their associates. The soft opening drew at least seven Cabinet secretaries.

Donald, Jr.,’s stake in Executive Branch hasn’t been disclosed, and the club’s bottom line is difficult to forecast. (Its ability to attract members after Trump leaves the actual executive branch is even more speculative.) The person involved told me that the founders saw the club as a “social vanity project,” comparable to the way many rich people dabble in the arts, and “not a money-making venture at all.” Still, the two hundred memberships have already sold. If twenty founding members paid half a million dollars and the rest paid a hundred thousand dollars, Executive Branch has already generated twenty-eight million. A deluxe renovation of the space, even at the extravagant cost of a thousand dollars a square foot, would still leave more than nineteen million. Given that association with the Trumps and their circle defines the club, Donald, Jr., would be foolish to expect less than a fifth of any profits. That would amount to more than $3.8 million before the club opens. But the person involved, listing various costs, made a strong case that running a high-end club is likely to burn through that sum quickly. Until it opens, then, Executive Branch’s profits remain hypothetical.

Malik has also paid Donald, Jr., in other ways. In the past several years, investment vehicles founded by Malik have acquired at least one company in which Donald, Jr., had already invested: PublicSquare, an “anti-woke” online marketplace. And Donald, Jr., was an adviser to an online gun retailer, GrabAGun, and received a stake—currently worth about two million dollars—as part of its acquisition by a Malik investment vehicle. Last fall, Malik made Donald, Jr., a partner in a venture-capital firm he co-founded, 1789 Capital, which looks to apply high-tech solutions to government failures and to exploit opportunities neglected by “woke” thinking. They have raised about a billion dollars for the company’s first fund, from such investors as the conservative mega-donor Rebekah Mercer. A person familiar with 1789 Capital’s fund-raising told me that the firm has also sought investors from the Persian Gulf. The firm backs only U.S. startups, and it has acquired minority stakes in several companies that are affected by the decisions of the federal government, including defense contractors. (Malik has stressed that nobody at the firm has ever worked with the federal government, and that it publicly discloses all its investments.)

It’s unlikely that Donald, Jr.,’s experience at the Trump Organization would have landed him any similar job in the venture-capital industry had his father never entered the White House. He hasn’t disclosed any of his compensation. But John Gannon, the chief executive of Venture5, a media company focussed on the venture-capital industry which conducts surveys of compensation, told me, “If Trump, Jr., is splitting his time between 1789 and his other responsibilities, it’s not unreasonable to assume a low-six-figure annual salary”—upward of two hundred thousand dollars. Most firms, by the end of a typical ten-year life span, at least double the capital they’ve invested. Under standard industry terms, the 1789 partners would then divide at least two hundred million dollars in profits. The firm’s website lists Donald, Jr., as the third among seven partners, after Malik and Buskirk. Gannon estimated that Donald, Jr.,’s share of those profits would be about ten per cent, so he might eventually take home at least twenty million dollars (present value: $16 million), in addition to a two-hundred-thousand-dollar salary (present value: $1.6 million). Excluding any provisional profits so far from the “social vanity project,” Donald, Jr.,’s take from 1789 and GrabAGun adds $19.6 million.

Estimated gain: $19.6 million

Running total: $1 billion

,

CRYPTO

Eric Trump, the public face of the Trump Organization while his father is in office, often says that his family first “fell in love with crypto” in the years after the Capitol riot. Big banks dropped the Trumps—including Deutsche Bank, their most important lender, and Capital One, where the Trump Organization had hundreds of accounts. At a recent crypto conference, Eric framed this blackballing, as he often does, as an example of bias against “a political view that might not have been popular with some of the big financial institutions.” He also described his family’s embrace of digital finance as a form of revenge: “The banks made the biggest mistake of their lives.”

Like many boosters of crypto, Eric sometimes struggles to explain what it’s good for, aside from crime and casino-like speculation. Cryptocurrency essentially refers to marks in an online ledger called a blockchain, which tracks the contents of digital wallets. The blockchain is like a giant spreadsheet in the sky—though, as the journalist Zeke Faux notes in his terrific account of the crypto boom, “Number Go Up,” its promoters often talk as if the system’s “incomprehensibility was almost a selling point.”

A hot topic among crypto investors is the question of a “use case.” At the recent conference, Eric responded to this by complaining, not for the first time, that it took him a hundred days to close a home mortgage: “Can you imagine how punitive that is to the average person out there that might not have our resources or might not have our net worth, you know, filling out paper forms?” Sometimes he gripes that Trump Organization executives still have to worry about getting large wire transfers done before banks close, at 5 p.m. “How, in 2025, could that possibly be the case?” he has said. “Crypto solves all these problems.” But outdated technology isn’t what slows down mortgage applications or big wire transfers; it’s the due diligence that banks perform to address the riskiness of a loan or the legitimacy of a payment. Molly White, a software engineer and a prominent skeptic of digital finance, told me that, for many boosters, getting around anti-money-laundering laws and other regulations appears to be the main appeal of crypto.

Indeed, criminals love crypto. The decentralized nature of that spreadsheet in the sky, maintained by a vast network of computers, makes it difficult to hold anyone accountable for unlawful transfers. Plus, each digital wallet is anonymous, identified by a string of letters and numbers, and often protected only by a hackable password. For years, the best-proved use case was Silk Road, a bitcoin-enabled black market in narcotics, hacking services, and other illicit transactions. In 2015, a federal court sentenced its founder, Ross Ulbricht, to life in prison for drug distribution, money laundering, and other crimes, and forced him to forfeit $183 million. Ulbricht reigned as the crypto-criminal goat until last year, when a court ordered the crypto savant Sam Bankman-Fried, a founder of the exchange FTX, to surrender eleven billion dollars in fraudulent gains.

Trump initially saw crypto with clear eyes. In 2019, he tweeted that the volatile prices of cryptocurrencies were “based on thin air,” and that “unregulated Crypto Assets can facilitate unlawful behavior.” As recently as 2021, he told an interviewer that crypto “seems like a scam.” FTX’s spectacular collapse, the following year, appeared to vindicate his warning.

But by then he’d got into the game. At the time, celebrity endorsements had driven a frenzy of speculation for non-fungible tokens, or N.F.T.s, which are essentially marks on that spreadsheet in the sky proving that a buyer has paid, often dearly, to own a digital image. Trump was reportedly introduced to the concept by Bill Zanker, the entrepreneur behind the Learning Annex. (Zanker had paid Trump to lecture about getting rich in real estate, and in 2007 the two men co-authored a book, “Think Big and Kick Ass: In Business and in Life.”) If Snoop Dogg and Paris Hilton were selling N.F.T.s, Zanker must have reasoned, why not Trump?

In Trump’s progression from brick-and-mortar developer to hawker of intangible projections of himself, his N.F.T.s were another milestone. They depicted him as a muscled superhero in a cape, a guitar-wielding biker, and so on, and on Truth Social he announced that they cost “only $99 each!” On his past three disclosure forms, Trump reported that he had earned $13,180,707 in N.F.T.-licensing fees. The forms also show that Melania Trump made $1,224,311 from licensing an N.F.T.

Estimated gain: $14.4 million

Running total: $1.02 billion

TOKEN INVESTMENTS

Trump collected some of his N.F.T. fees in the form of digital currency, giving him his first incentive to start talking it up. In December, 2023, Arkham, a research firm, reported that a digital wallet linked to Trump held about four million dollars’ worth of crypto. On his most recent disclosure form, Trump reported that his digital wallet contained at least a million dollars’ worth of crypto.

Trump, in contrast with Eric, has said that his love affair with crypto began in 2024. At a bitcoin conference that July, he warned the audience that “most people have no idea what the hell it is—you know that, right?” But his Presidential campaign had begun receiving big contributions in crypto. If he still sounded hazy about how it all worked, he nonetheless promised the conference attendees that he’d make the U.S. “the crypto capital of the planet.” He also repeated a pledge to free Silk Road’s Ulbricht. (In January, Trump pardoned Ulbricht.)

Around the time of that conference, Donald, Jr., and Eric started dropping hints about a new crypto venture of their own. It formally appeared in September, 2024, under the name World Liberty Financial. The company entered a sector known as “decentralized finance” that involves the borrowing, lending, and trading of cryptocurrency. Competitors already filled the field, and nobody at World Liberty had a successful track record in decentralized finance. The startup offered few details about its plans, saying only that it would begin selling digital tokens that entitled a buyer to vote, at some point, on what its future plans would entail. The tokens somewhat resembled stock certificates, except that they conferred no share of the company’s profits, couldn’t be sold or transferred, and came under scant government regulation. Accordingly, only non-Americans and certain big investors could legally buy them. The founders said that they intended to raise three hundred million dollars by selling the tokens, but by the start of November World Liberty had brought in only $2.7 million.

Soon, however, World Liberty had an edge—the President. The company billed itself as the only decentralized-finance company “inspired by Donald J. Trump.” A photograph of Trump raising his fist dominated the company’s website, which called him its “chief crypto advocate.” Trump participated in a desultory two-hour live stream introducing the company, in which he portrayed investing in crypto as a kind of national duty, “whether we like it or not.” The President’s youngest son, Barron, an N.Y.U. freshman, was also involved in the company, as were Steve Witkoff’s sons, Zach and Alex. Most of World Liberty’s profits belonged to the Trumps, too. The company’s website said that the President had agreed “to promote the WLF and the WLF protocol from time to time,” and in exchange a shell company controlled by his family would receive roughly three-quarters of the revenue from the voting token. World Liberty initially said, on its website, that the Trumps would own sixty per cent of its eventual business; around June, it lowered that to forty per cent, without explanation. White, the crypto skeptic, told me that it was still unclear what, if anything, the Trumps might have contributed other than their name: “The whole thing has been a Trump business that aimed to give some plausible deniability to the Trumps.” (Cynical buyers of the token may have bet that if Trump won the election and loosened crypto rules, World Liberty might let investors resell their tokens, potentially at a profit. The rules did indeed relax, and in July the company announced that it will allow trading. The Trumps, as part of their deal to promote World Liberty Financial, were given millions of tokens, which they will be able to unload.)

The Trump connection began paying off shortly after his election, beginning with a bellwether investment by Justin Sun, a Chinese-born crypto billionaire. Sun founded a crypto network called Tron and his own cryptocurrency, Tronix. In 2023, the S.E.C. accused him of orchestrating bogus trades in order to fraudulently inflate prices. The S.E.C. also said that he’d made undisclosed payments to Lindsay Lohan, Lil Yachty, and other celebrities to get them to hype his crypto; the celebrities agreed to turn over more than four hundred thousand dollars in penalties and illicit gains. The S.E.C. further alleged that, although Sun could not legally sell to Americans, he had found furtive ways to do so. (He has denied any wrongdoing.) Nonetheless, crypto traders revered him for his riches. After Trump’s 2024 victory, Sun bought $75 million in World Liberty tokens and signed on as a formal adviser. Not long after the Inauguration, Sun’s imprimatur had helped bring in $550 million; the Trump family’s cut appears to be about $412.5 million. (Trump reported an initial $57.4 million from World Liberty on his latest financial disclosure.) Trump’s new Administration soon ended virtually all legal or regulatory actions against crypto traders, and on February 26th the S.E.C. put its case against Sun on hold, with the aim of negotiating a resolution.

Estimated gain: $412.5 million

Running total: $1.4 billion

THE CRYPTO GULF

In March, World Liberty announced that it would sell a type of cryptocurrency known as stablecoin. Unlike buying bitcoin or other digital assets, purchasing stablecoin is supposed to resemble putting money into a checking account. A buyer can pass them to other digital wallets the way you might transfer money from one checking account to another; an owner of stablecoin should always be able to redeem them for dollars, at a constant value. Until July, stablecoins were largely unregulated, and the best known have become a mainstay of money laundering; some issuers, meanwhile, have diverted supposedly secure deposits into crypto Ponzi schemes.

World Liberty, however, offered the special credibility of a Presidential endorsement, and promised to back its stablecoin, USD1, with short-term U.S. Treasury bills. In the interval between the sale of USD1s and their redemption for dollars, the company stood to profit from interest that it would earn on those T-bills. At present Treasury yields, World Liberty can earn more than four per cent annually on the value of any stablecoin it sells—a profitable business with little risk, if the company can persuade buyers to embrace USD1.

On May 1st, Zach Witkoff, flanked by Justin Sun and Eric Trump, announced at a crypto conference in Dubai that a company owned by the U.A.E.’s ruling family had become World Liberty’s first major stablecoin customer, buying two billion dollars’ worth of USD1. Doing business with the U.A.E.’s rulers posed an obvious conflict of interest for the Trumps. But it was equally significant that the Emiratis planned to use USD1 as payment for a stake in Binnacle*, the world’s largest crypto exchange. Binnacle* and its controlling shareholder, Changpeng Zhao, known as C.Z., pleaded guilty in 2023 to evading U.S. sanctions and violating anti-money-laundering laws. He served two months in prison; Binnacle* agreed to pay $4.3 billion in fines and forfeiture, and to submit to government monitoring. Binnacl* will now determine when to cash in the two billion dollars in stablecoin from the Emiratis, thus controlling World Liberty’s ability to collect interest on it. That gives C.Z. leverage over the Trumps at the same time that government-appointed monitors are supervising Binance. In May, C.Z. acknowledged on a podcast that he’d applied for a pardon. Binnacle* has reportedly also sought to have its monitoring withdrawn.

Bloomberg News recently reported that Binnacle* accounts for ninety per cent of the USD1 in circulation. If C.Z. holds on to it for the remainder of Trump’s term, and Treasury interest rates stay at or above their current level, World Liberty will likely make more than $280 million. Under the ownership split at the time of the sale, about $168 million would go to the Trumps. I’d be surprised if Binnacle* sells while Trump is in office.

Two weeks after World Liberty’s announcement in Dubai, Trump declared that the U.S. would provide the U.A.E. with advanced technology for a joint ten-square-mile artificial-intelligence data center. This decision overrode long-standing American concerns that the U.A.E.’s close ties to China made it vulnerable to espionage and to the theft of sensitive technology. Some news outlets have reported that those security concerns might yet stop the project; but, if completed, it could vault the tiny monarchy to the forefront of the A.I. race—and lock the U.S. in to dependence on Abu Dhabi.

With the data center awaiting final approval, a shadowy new Emirati fund, the Aqua 1 Foundation, announced on June 26th that it would buy a hundred million dollars in World Liberty voting tokens. Aqua 1, which has no public history, said in a statement that it would make the hundred-million-dollar payment “to participate in governance of the decentralized finance platform inspired by President Donald J. Trump.” Since World Liberty has said that the Trump family gets roughly seventy-five per cent of the proceeds from sales of those tokens, that’s seventy-five million in Trump profits. This would bring the family’s profits from Emirati deals with World Liberty to $243 million.

* Binnacle is a replacement name for a firm that is called Bi nance. The platform on which the Roundup is published will not allow that term.

Estimated gain: $243 million

Running total: $1.7 billion

AMERICAN BITCOIN

The origins of the Trump family’s third crypto business date back about five years, to when Donald, Jr., and Eric got to know Kyle Wool, a stockbroker who had recently left Morgan Stanley. Wool wore his hair in the slicked-back style of Michael Douglas in “Wall Street” and golfed at the Trump club in Jupiter. At the time, he oversaw wealth management at an obscure brokerage, Revere Securities. (Morgan Stanley paid fifty thousand dollars to settle a lawsuit claiming that Wool had made unauthorized trades with a client’s money—one of several similar allegations he has faced. He has denied any wrongdoing.)

Wool’s career path from there has been convoluted. He joined the board of Aikido Pharma, a penny-stock biotech company that had reported no revenue for years. Wool helped Aikido transform itself into another small brokerage, called Dominari Holdings. The company rented office space in Trump Tower, and in 2023 Wool became the C.E.O. of its main business, Dominari Securities. It has reported losses of more than fourteen million dollars in each of the past three years.

In early February, Donald, Jr., and Eric joined Dominari’s board of advisers and were given a roughly six-million-dollar stake in the company. In the days before this was announced, Dominari’s share price doubled, to six dollars—it’s not clear why—and afterward it doubled again, giving the Trumps a sizable paper profit. On February 18th, Dominari and the Trump brothers announced a new joint venture—a third of it owned by Dominari, virtually the rest by the Trumps—which would invest in A.I. data centers.

A month later, they sold most of that nebulous partnership, at a windfall profit, to Hut 8, a publicly traded bitcoin miner. (“Mining” refers to computing involved in tracking and recording bitcoin transactions on the blockchain—that spreadsheet in the sky. Under the software protocol governing bitcoin, miners receive new bitcoin as payment for this computational labor.) Hut 8 had agreed to buy eighty per cent of the Trump-Wool partnership. As payment, it contributed to the new company almost all of its mining operation—including equipment that, according to a press release, was worth a hundred million dollars.

It’s unclear what the Trump brothers added to the new company, to be called American Bitcoin, aside from their family name. They haven’t disclosed any financial contribution or payment, but they will own about thirteen per cent of the company—indirectly owning thirteen million dollars’ worth of equipment. Molly White told me that many people in the industry believe that, to a crypto company like American Bitcoin, “the Trump name alone is worth thirteen million.” Investors would bid up the company’s price purely “because it is associated with the President,” she argued. In a press release, Hut 8 said that Eric Trump would be American Bitcoin’s “chief strategy officer,” and praised his “commercial acumen, capital markets expertise, and commitment to the advancement” of crypto.

Other metrics suggest that the Trumps’ stake could be worth a lot more than thirteen million dollars. American Bitcoin plans to become publicly traded by merging with a penny-stock bitcoin miner, Gryphon Digital Mining. Bitcoin miners typically trade for three or four times the value of the crypto they produce in a year. At current prices and recent mining rates, that could put the value of American Bitcoin at about $610 million, making the Trumps’ stake worth about $79 million. In an interview with a crypto website, Eric Trump said that he got “a little special twinkle” in his eye whenever he saw the Dominari team, adding, “They’ve brought a lot of great things to us in the past, and so many of those great things have worked out so incredibly well.”