Friday, August 15, 2025. Annette’s Roundup for Democracy.

Mr. Trump is going to Russia. Alaska.

Trump: It’s embarrassing. I’m going to see Putin. I’m going to Russia on Friday.

— Acyn (@Acyn) August 11, 2025

(Alaska) pic.twitter.com/ET7e6zMS3c

Yes, he called Alaska Russia twice on Wednesday. The United States bought Alaska from Russia in 1867. It’s been a state since 1959.

** What to expect from the Trump-Putin meeting.**

Trump is serving two masters here:

- His narcissistic desire to win a Nobel Prize.

- Putin who seems to control him.

In case you think I am too cynical about Trump’s focus on the Nobel Prize, read this post from yesterday’s Politico.Eu. 👇

Trump cold-called Norwegian minister to ask about Nobel Peace Prize

One more thing.

Keep in mind that Trump follows Putin’s lead even in wall design.

Guaranteed Income is a big topic, even in places you might not expect.

Every year, Americans face the unfortunate fact that their health insurance is often attached to their employment. Losing employment often leaves people without health insurance - and subsequently health care.

What if we now have to face the fact that employment which provides most of us with the money which gives us access to home, food, health, education, safety, comforts - grows more tenuous every day.

AI is here, and the threat is not just to our health care.

Losing employment may soon be a reality for millions of people, not just the few who social changes on a continual basis leave unemployed.

How will society meet this challenge?

It is time to think about AI and UBI - universal basic income.

AI is making ever more jobs obsolete. The solution from Silicon Valley? A universal paycheck, no work required.

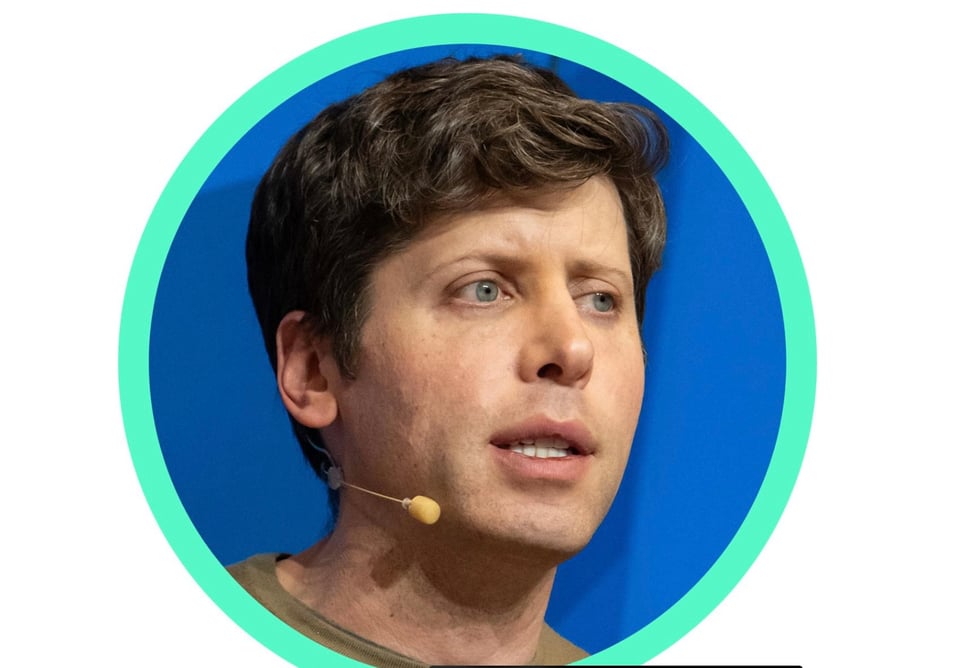

Technology titans including Elon Musk and Sam Altman see a future flush with wealth generated by artificial intelligence. Some tech heavyweights have endorsed no-strings cash distributions for a decade, so-called universal basic income, or UBI.

While many think of UBI as a taxpayer-funded system, Silicon Valley’s elite envision AI doing humans’ work, from mundane factory jobs to highly skilled white-collar roles, and funding payouts through cost savings and more revenue. Tech leaders say that revenue can be shared under a massive wealth-redistribution system.

Suddenly, an idea once seen as a socialist policy that would reward idleness is one of the AI boom’s hottest acronyms.

What is UBI?

Economists and welfare-rights activists began advocating for UBI in the 1960s as a solution to poverty. As mainframe computers popped up in offices that same decade and sparked job-loss fears, proponents wondered if UBI could be the solution to technology displacing humans, said Karl Widerquist, a philosophy professor at Georgetown University in Qatar.

Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey and Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes have spent millions over the past several years on pilot projects. Some current UBI trial programs aim to reduce poverty or respond to explosive automation, sharing donor and grant money with individuals or families.

Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, funded an experiment starting in 2016 that gave $1,000 in cash to a group of low-income individuals each month for three years. Recipients worked slightly less and mostly spent on basic necessities, said Elizabeth Rhodes, who ran the OpenResearch study.

Altman said in an appearance on Theo Von’s “This Past Weekend” podcast in July that he now thinks that instead of money, everyone could receive “an ownership share in whatever the AI creates.” That would allow the wealth accumulated by AI to be spread across the population, he said, calling the idea “universal extreme wealth.”

He imagined a scenario in which every human is given a trillion tokens, the basic unit of information that large language models use, each year to sell or treat as personal wealth—an alternative to all wealth being consolidated in the “normal capitalistic system.”

Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla, touts “universal high income,” the concept that AI will automate most production and the public can share in the revenue.

Musk said at a forum in May that universal income could create a “Star Trek future” with “a level of prosperity and hopefully happiness that we can’t quite imagine yet.” (He also warned that if handled incorrectly, we could end up with a “Terminator” future.)

Marc Benioff, CEO of Salesforce, has said up to half of the work at the company is now done by AI. He is an evangelist for universal basic income and said during the pandemic that he sees Covid-19 stimulus checks as a model for broader income distribution.

He wrote that automation will drive income inequality and necessitate supplemental income “for those who cannot be retrained, and even those traditionally not compensated for raising a family or volunteering to help others,” in a Fortune article. He has said that AI will generate wealth by lowering costs for companies.

The Critics

Not all of Silicon Valley—or the public writ large—is on board. Critics think universal income is politically unrealistic and allows tech companies to justify increasing unemployment and wealth disparities.

David Autor, a labor economist at MIT, said the hypothetical society in which the majority of income is distributed from a few sources is frightening and a “political fantasy land.”

AI leaders support universal income because “they think they’re gonna put everyone out of work and they don’t have a better idea for what to do about that,” he said.

He wondered what would happen to people outside of the U.S., who could lose their work without receiving universal income.

Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen argued in his 2023 “techno-optimist manifesto” that humans need to work to feel fulfilled.

“Man was meant to be useful, to be productive, to be proud,” he wrote.

Andreessen thinks AI will transform almost every job. He wrote on Substack that UBI is unnecessary because the government is likely to subsidize most industries.

David Sacks, President Trump’s AI czar, said on his “All-In” podcast last year that tech magnates seeking fortune from the AI boom use the idea of handing out money to assuage concerns about job losses, but that doing so doesn’t serve society.

He posted on X in June that universal income is a “fantasy” of “welfare” that is “not going to happen.” (Wall Street Journal).

The Left-Wing Policy That AI Evangelists Suddenly Love.

Alas, they love it for all the wrong reasons.

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman at a Senate committee hearing in May.

The robots are coming for our jobs—again. Last month, The New York Times profiled an AI startup called Mechanize, Inc., whose founders were brutally honest about its goals: to automate the entire workforce within the next 30 years. But one of them, Tamay Besiroglu, tried to assuage those who might fear such a future. As tech reporter Kevin Roose wrote, “Mr. Besiroglu said he believed that A.I. would eventually create ‘radical abundance’ and wealth that could be redistributed to laid-off workers, in the form of a universal basic income that would allow them to maintain a high living standard.”

Besiroglu’s assurances about a universal basic income—a policy whereby the government gives everyone in society an equal amount of money—seemed cavalier at best, an easy way to dismiss worries that AI will put millions of people out of work. So I reached out to Besiroglu for comment. He agreed to provide comments, but once I sent him questions, he responded: “I’m sorry, but I’m too busy to engage at this point.”

No matter. He’s hardly the first denizen of Silicon Valley to suggest UBI as a balm for the decimation of the workforce. “I’ve been intrigued by the idea for a while,” OpenAI CEO Sam Altman wrote in a 2016 blog post announcing that he would help fund a UBI study (it was conducted in Illinois and Texas, and it ended last year). “I’m fairly confident that at some point in the future, as technology continues to eliminate traditional jobs and massive new wealth gets created, we’re going to see some version of this at a national scale.”

Altman’s archnemesis has also weighed in on this “necessary” policy idea over the years. Predicting that “there will come a point where no job is needed” because “AI will be able to do everything,” Elon Musk last year said society will have something even better than UBI: “We won’t have universal basic income. We’ll have universal high income. In some sense, it’ll be somewhat of a leveler, an equalizer.”

UBI existed long before AI’s proponents decided to champion it; hundreds of trials have yielded positive results. But the notion that an AI revolution will magically usher in this left-favored policy is relatively new—and utterly misguided. Even if AI creates an age of abundance, as Musk has predicted, there is no guarantee that this vast wealth would be distributed equally in the form of UBI or any other redistributionist policy. Governments must enact UBI, which means it requires widespread political buy-in.

A question, then, for Besiroglu and the rest of UBI’s proponents in the AI industry: Have you looked at what’s happening in Washington lately?

Americans are already deeply suspicious that AI will have a positive, rather than negative, effect on their lives. They’re right to fear it: A rise in unemployment among new college graduates has been partly blamed on AI, and entry-level jobs may be disappearing in some industries like software engineering. Meanwhile, bosses are using the prospect of AI to scare workers: Last month, Axios reported that managers at some tech companies were warning employees that their jobs could easily be replaced by AI, while also pressuring them to learn to use AI in the workplace.

Trying to motivate employees by fear almost never works, but the truth is that AI is already changing the labor market—and it’s too early to fully fathom how much it may transform not only the economy but how we live our lives. Even so, for UBI to be a solution to widespread, AI-fueled unemployment would require a massive leap forward in the American welfare state.

So far, UBI has been limited to experiments and demonstration projects in the U.S. and abroad among targeted populations. The incomes usually max out at about $1,000 a month, which is not enough to replace work. “Basic” is right there in the name: UBI would create an income floor that people cannot drop below, but it is not often proposed as a way to replace entire household incomes indefinitely. When touting these programs, proponents usually point to how it helps recipients look for better jobs or go back to school. That is, UBI is a bridge to better work, not an employment replacement.

At the same time, it’s not just cash welfare reborn, because its aim is to have fewer strings attached and be easier to access. “It’s not a net that holds people and keeps them safe,” said Natalie Foster, president and founder of the Economic Security Project. “It is a trampoline where people can have a floor that they cannot fall through and then jump up and live the lives of agency and dignity and live on their own terms, which you can’t do if you’re working hand to mouth, or if you are in deep economic uncertainty, which is what the future holds without bold policy interventions.”

There are conversations we need to have about UBI, separate from its potential as a salve for a labor apocalypse. At the same time, the development of AI requires a discussion about what the industry owes society for the damage it will cause. “AI’s worth is created by all of our data, all of our experiences, so everyone should have an ownership stake in that,” said Michael Tubbs, the former mayor of Stockton, California, who ran an AI project in his city—which TNR featured in 2020—and now works with an organization called Mayors for Guaranteed Income. “People who are going to be harmed have to have an ownership stake.”

Who works, how much they work, and how they’re compensated are political questions. Productivity gains over the past several decades have led to benefits for the very richest Americans, but many of us are working harder than ever without seeing gains. If we don’t tackle these issues in the right way, our future will be even more unequal than today, with the tech billionaires further enriched while the rest of us struggle to find new jobs and are encouraged to retrain or work harder. “I’m afraid inequality is likely to continue getting worse,” said Dr. Stuart Russell, a professor of computer science at UC Berkeley. “Most of the gains are likely to go to the owners of the technology.” And AI may hit white-collar jobs as severely as blue-collar jobs were pummeled by past technological changes.

For decades, economists and futurists have promised that technology gains will lead to increased leisure—famously, the economist John Maynard Keynes thought his grandkids would work 15 hours a week—and it largely hasn’t come to pass. It’s broadly true that we work less per week than our predecessors, Russell said. “Having said that, we’re certainly not living a life of leisure: As productivity improves, we are consuming a lot more rather than working a lot less.”

“There have been, across generations, people in society who have thought that the future that they wanted to build for the rest of us—who didn’t get asked about the future that we wanted—was one without jobs,” said Dr. Alondra Nelson, a leading scholar who helped draft a Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights under President Joe Biden. “I think what is different about this moment is it has now been paired with the opportunity for people who are promoting that vision of the future … to also make a lot of money.”

Nelson pointed out that if the people developing AI fulfill part of their promises to investors about their products’ capabilities, they will probably sell their companies for untold billions of dollars—so their futures might very well be jobless.

There’s something revealing about the way AI techs speak about work, too, which Nelson finds naïve. “It’s as if work is only a kind of burden,” she said. “I know that work fulfills a lot of other roles in our lives. Work is also about how we create community. It’s how we shape our identities, etc. And so to just hand people money … doesn’t solve the sort of question, or the issue of social cohesion and the social connection, the social identities that come with having work.”

That’s a question that few AI evangelists are answering, or even asking. It’s taken as a given that everyone desires a life of full-time leisure and has passions they would pursue if money weren’t an object—just as it’s assumed that AI, by creating abundance and prosperity like we’ve never seen before, will benefit society as a whole (or even “save the world,” as Marc Andreessen declared).

“If we want better health, if we want better science, better applications in health care and climate science and education, none of these things just emerge magically out of an AI system,” Nelson said. Policymakers would need to ensure those outcomes—that is, by passing laws that regulate AI. That’s not in the offing these days. (In fact, the Senate’s version of the Republican budget bill had a provision preventing states from regulating AI for the next 10 years, but it was struck in the eleventh hour.)

“Right now, the future of AI is really being shaped by a few powerful tech companies, the same companies that have concentrated their power and wealth since the internet boom and, through their sheer size and force, have been able to move forward with no regulation,” Foster said. “In addition to the social policy needed, it’s also [a question of] the policy needed to deal with these concentrated markets.”

History shows us that new technology tends to create new jobs, rather than simply replacing them with automation. The fight today needs to be about what kinds of jobs AI will create, who will have access to them, and what benefits they will provide to our society broadly. That conversation should include UBI, which may be even more vital if Republicans pass their budget bill, which includes drastic cuts to the safety net.

“I think we need to build the political will to get there, and we need to elect people who have a bold vision for the cost of living crisis, and hold them accountable to enacting that vision,” Foster said. “We have the blueprints for how to do it. We just need the political will.(Monica Potts, The New Republic)

George C. White, Founder of Eugene O’Neill Theater Center, Dies at 89.

His summer conferences gave budding playwrights a chance to try out new works, many of which went on to success in New York.

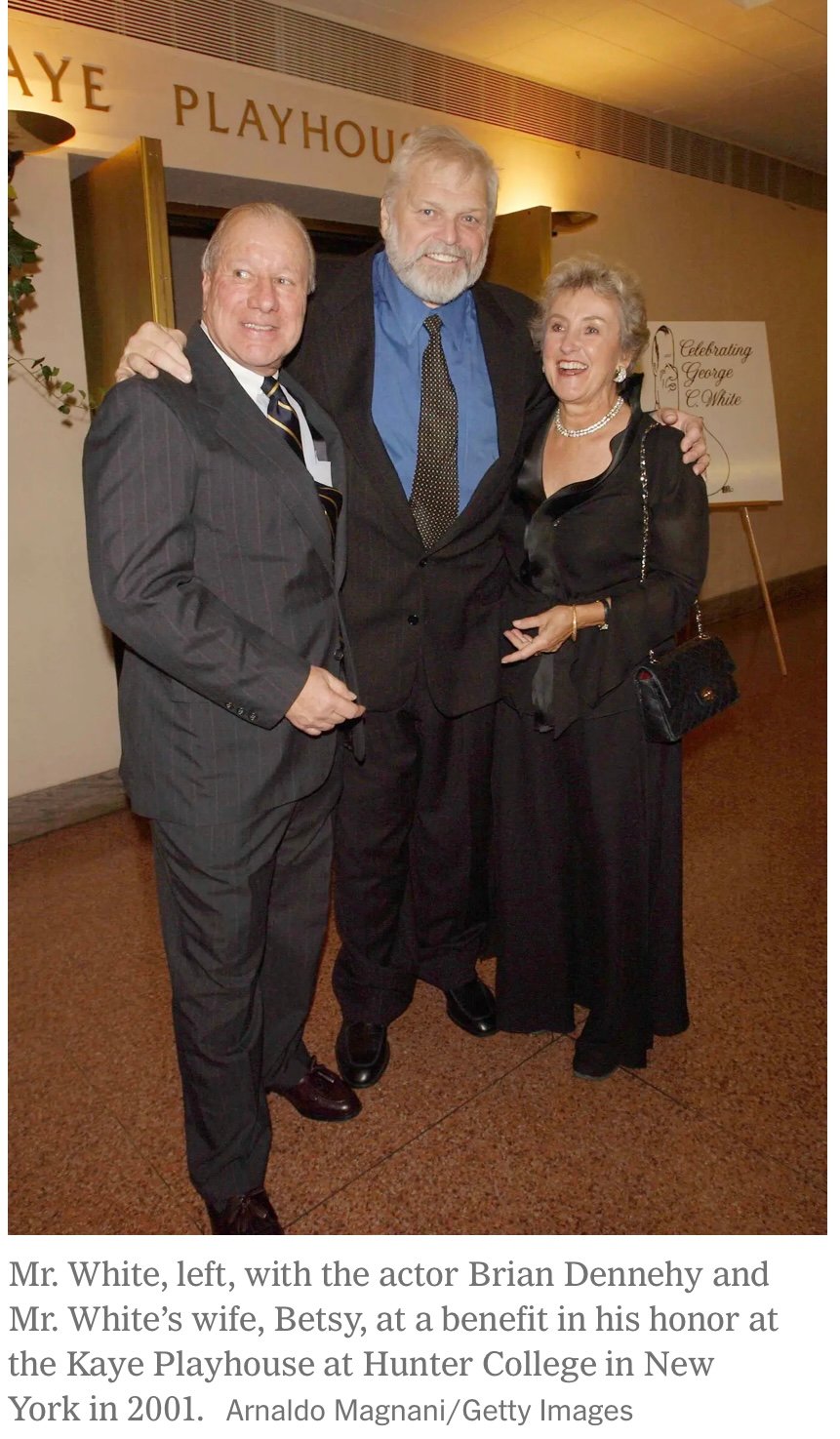

George C. White in an undated photo. Since its first summer conference for playwrights was held in 1965, his Eugene O’Neill Theater Center has helped incubate generations of new talent, including John Guare, August Wilson and Sam Shepard

George C. White, whose Eugene O’Neill Theater Center, on an idyllic waterfront estate in Connecticut, gave generations of budding playwrights a chance to try out their latest works — many of which went on to success in New York and elsewhere — died at his home in Waterford, Conn., on Aug. 6, 10 days before his 90th birthday.

His children, Caleb White, George White and Juliette White Hyson, said the cause was congestive heart failure.

Since its first summer conference for playwrights was held in 1965, the O’Neill, named in honor of the playwright who spent much of his life in nearby New London, has helped incubate generations of new talent, including John Guare, August Wilson and Sam Shepard, all of whom made the trek to eastern Connecticut.

There, on a sprawling property that rolled down to Long Island Sound, they lived, ate and worked together, far from the pressure exerted by producers, critics, actors and everyone else who, for better or worse, shape the public presentation of a play.

Mr. White, the child of an artistic, semi-patrician Connecticut family who founded the center when he was in his 20s, called himself its “innkeeper.” He spent most of the year in New York, raising funds and running the admissions process, and migrated north in the summer to run the O’Neill’s day-to-day operations.

“There have been plays here over the years that I think are pretty awful,” he told The New York Times in 1982. “But I stand behind the selection of the playwright every single time. We really are looking for the playwright who shows promise, more than the play that can be a hit.”

Though Mr. White was an accomplished director in his own right, he relied on Lloyd Richards, the longtime head of the Yale School of Drama, to act as the center’s artistic director.

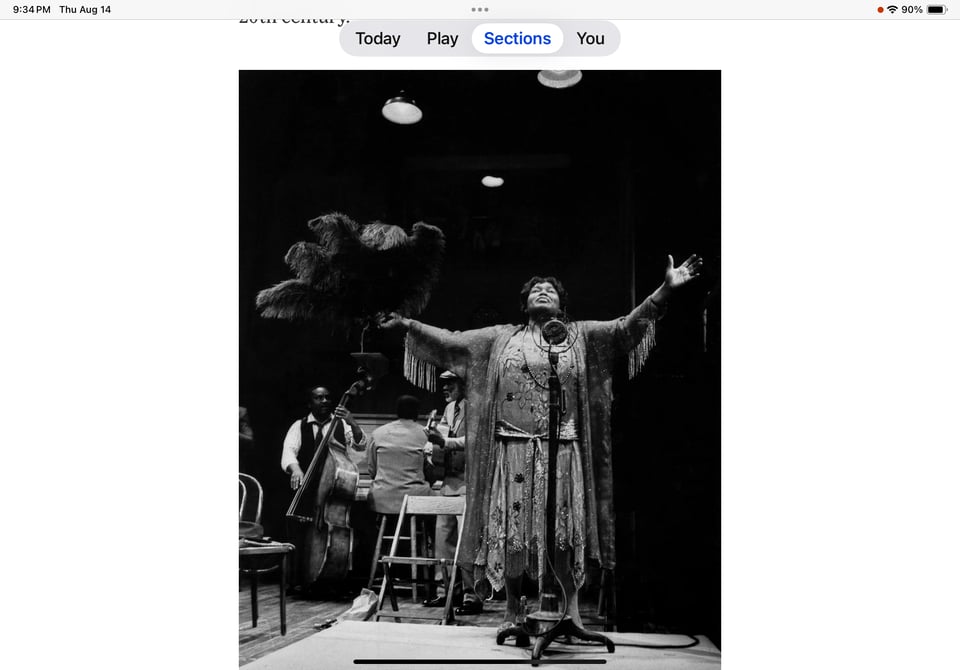

Together they developed an unerring eye for new talent. Famously, they accepted an unsolicited script from Mr. Wilson, who was still unknown at the time; the work, “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” was nominated for the Tony Award for best play in 1985 and established Mr. Wilson as one of the great American playwrights of the 20th century.

Theresa Merritt in a scene from August Wilson’s play “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” at the Yale Repertory Theater in New Haven, Conn., in 1984. Mr. White and the center’s artistic director, Lloyd Richards, famously accepted Mr. Wilson’s unsolicited script.

Other noted plays and musicals (which got their own, similar conference in 1978) that originated at the O’Neill included Mr. Guare’s “The House of Blue Leaves” (1966), Wendy Wasserstein’s “Uncommon Women and Others” (1975) and Robert Lopez, Jeff Marx and Jeff Whitty’s “Avenue Q” (2003).

Mr. White cultivated a reliable network of actors to perform staged readings of each play. They, too, were drawn from the ranks of the young and promising, and many were destined for fame: Michael Douglas, Charles S. Dutton, Meryl Streep and Al Pacino, among others, did time at the O’Neill early in their careers.

“He took his privilege and used it to share the goodies for a wide community,” Jeffrey Sweet, the author of “The O’Neill: The Transformation of Modern American Theater” (2014), said in an interview. “And he did it with just enormous heart and enthusiasm.”

George Cooke White was born on Aug. 16, 1935, in New London, not far from Waterford, where he grew up. He came from a long line of noted landscape painters, including Henry C. White, his grandfather; Nelson C. White, his father; and Nelson H. White, his brother.

His mother, Aida (Rovetti) White, came from a working-class family and was a seamstress before she met his father. She later served on the O’Neill’s board.

George studied drama at Yale. After graduating in 1957, he spent two years in the Army, stationed in Germany, where he met Elvis Presley, who was already a singing sensation but wanted to do more acting. He asked Mr. White for advice, and they spent an afternoon running through a monologue.

After his discharge, Mr. White studied at the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon, England, and then returned to Yale to get an M.F.A. in drama. He graduated in 1961 and moved to New York, where he worked for the television producer and talk-show host David Susskind.

Mr. White married Betsy Darling in 1958. Along with their children, she survives him, as do his brother and 10 grandchildren.

One afternoon, Mr. White, an avid sailor, was tacking past the Hammond Mansion, an empty seaside home that was slated to be used for firefighting practice by the town of Waterford.

He was already thinking of starting his own theater in honor of O’Neill, and he asked the town if he could lease the estate. Happy to help a local boy, the town gave it to him for $1 a year. The Eugene O’Neill Theater Center opened there not long after.

Mr. White initially wanted to stage full productions at the site, drawing on the connections he had built under Mr. Susskind’s tutelage. But even with his prodigious people skills, the task proved daunting, and in the interim he held his first summer conference for young playwrights.

The conference was a hit, and he soon abandoned his original plans, focusing instead on cultivating new talent. He also began hosting similar conferences on theater criticism and musicals — Lin-Manuel Miranda workshopped “In the Heights” at the O’Neill before taking it to New York.

Mr. White retired in 2000 but remained involved with the O’Neill, and with theater generally. He was particularly active with other organizations that took the O’Neill as their model. Robert Redford, for instance, used it as a template for his Sundance Institute, focused on young filmmakers, and Mr. White agreed to serve on the Sundance board.

He also served in the United States Coast Guard Auxiliary as a flotilla commander; in 2014, the Coast Guard gave him its distinguished public service award.

Like many theater programs around the country, the O’Neill has struggled in recent years. This year, the federal government clawed back some of its funding, and the O’Neill has had to slash its budget and employment rolls in response.

But Mr. Sweet, the author of “The O’Neill,” said that Mr. White’s legacy had put the O’Neill in a better place than other endangered programs.

“It’s going to be belt-tightening for a while,” he said. “But I think there’s such a huge community of people who view the O’Neill as one of their homes, and a lot of them are famous and rich. A lot of them owe a lot to it.” (New York Times)