Friday, August 1, 2025. Annette’s News Roundup.

One long article caught my eye. 👇 Enjoy.

Things may not be what they seem to be.

Who are you supporting when you support no tax on tips?

“No Tax on Tips” Is an Industry Plant

The poverty rate among tipped workers is more than double the rate of other employees.

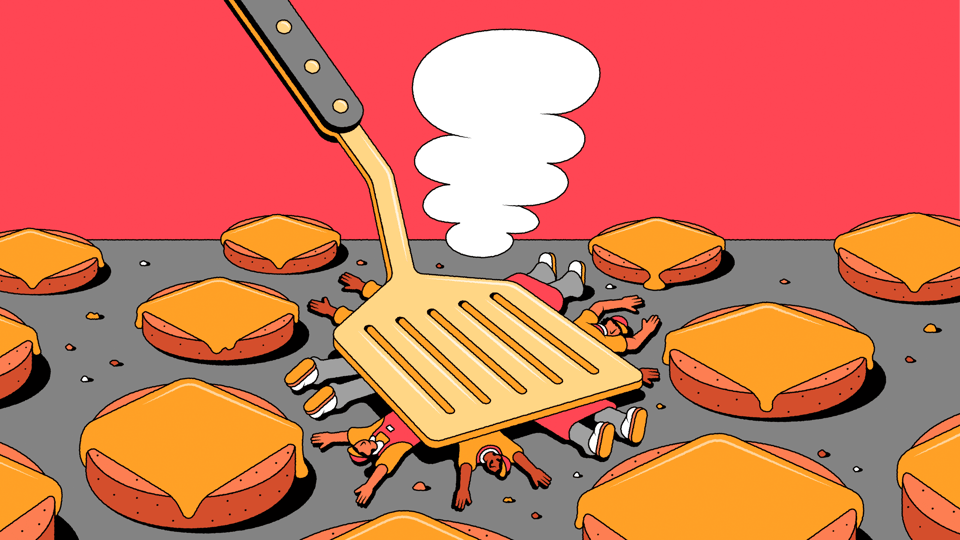

Illustration by Till Lauer.

Trump’s “populist” policy is backed by the National Restaurant Association—probably because it won’t stop establishments from paying servers below the minimum wage.

Hearings before the Commerce Committee of the Arizona House of Representatives normally draw a modest crowd of lobbyists in suits. On March 19, 2024, a throng of people in more casual attire appeared. They wore matching green T-shirts adorned with the message “Save Our Tips.” The slogan caught the eye of Analise Ortiz, a Democrat on the committee. She assumed that the visitors were bartenders and waitstaff who had come to voice opposition to a bill that could lower their salaries.

The bill was called the Tipped Workers Protection Act, a name that disguised its true purpose. The legislation, if approved, would place an initiative on that November’s ballot to amend the Arizona constitution so that employers could pay tipped workers twenty-five per cent less than the state minimum wage, then $14.35 an hour. In Arizona, the minimum wage for such workers was already $11.35 an hour. The formula being proposed would allow employers to pay tipped workers just $10.76 an hour—a pay cut that would reduce a full-time server’s annual salary by twelve hundred dollars.

Ortiz, who had worked at a restaurant to help pay for college, knew from experience that servers were vulnerable to exploitation and mistreatment. She’d noticed that the chief supporter of the Tipped Workers Protection Act was the Arizona Restaurant Association, an industry lobby that represents the interests of owners. It had persuaded Republicans to introduce the measure as a way of blocking another ballot initiative, the One Fair Wage Act, which called for raising Arizona’s minimum wage to eighteen dollars an hour and insuring that by 2028 tipped workers would be paid that amount (without relinquishing their gratuities).

As the hearing progressed, Ortiz expected the workers in the green T-shirts to explain why they deserved a raise or, at the very least, did not want their salaries lowered. But, when three members of the group came forward to testify, all expressed support for the Tipped Workers Protection Act and opposition to the One Fair Wage Act, which they portrayed as an effort to steal their tips. A waitress named Jaime Sarli said, “If restaurants had to pay us more money and eliminated tips, why would I want to do this?” She explained that she made such “great money” as a server that she’d turned down salaried managerial positions. “I don’t want to work a minimum-wage job,” she said.

Ortiz, who is now a state senator, told me that, as she listened, she “became confused.” The One Fair Wage Act proposed guaranteeing servers a full minimum wage that would still be supplemented by tips. She found it odd that workers would instead promote a bill that cut their base salaries, especially at a time when the price of virtually everything—food, gas, rent—was rising. Ortiz subsequently came across a video, produced by a YouTuber called HistorySock, that clarified what she’d witnessed. The Save Our Tips activists all had ties to the Arizona Restaurant Association, the video revealed, and none were entry-level servers. Sarli, the waitress who’d testified about her fantastic tips, was an assistant manager at Streets of New York, a pizza chain whose owner, Lorrie Glaeser, was the vice-chair of the Arizona Restaurant Association’s board. Beth Cochran, who testified after Sarli, was the vice-president of Snooze A.M. Eatery, a breakfast chain, and served on the same board. “These people were management and were advocating for a bill that would allow them to undercut their own workforce,” Ortiz said. “That really upset me.”

Some workers at the hearing did speak against the Tipped Workers Protection Act. Meschelle Hornstein, a waitress at a restaurant in the Phoenix airport and a member of the trade union Unite Here, said that the measure “would harm the working-class people that make up the majority of tip positions.” Her testimony didn’t persuade the Republicans on the committee. One of them said, “Except for some of the unions, it’s clear the employees are happy with the situation as it is.” This message was echoed by Dan Bogert, the chief operating officer of the Arizona Restaurant Association, who urged the committee to “really just listen to the workers who are here.” He didn’t mention that the slogan on the green T-shirts matched the name of a new political-action committee, Save Our Tips AZ, that his organization was funding. According to a form filed with the Arizona secretary of state last October, the pac received nearly a quarter of a million dollars from the Arizona Restaurant Association in the months that followed. The form was signed by Bogert, who was listed as the pac’s treasurer.

Until recently, tipped workers were politically all but invisible. This changed last summer, when Donald Trump appeared at a campaign rally in Las Vegas. Nevada was a swing state with many tipped employees in hotels, night clubs, restaurants, and casinos. Trump had a message for such workers: “You’re going to be very happy, because when I get to office we are going to not charge taxes on tips.”

Had Trump abandoned this pledge after winning Nevada and the general election, few observers would have been shocked. During his first term, the Department of Labor had hardly championed the interests of tipped workers, issuing a proposal that would have enabled restaurant owners to pocket pooled tips, under the guise of redirecting them to untipped, back-of-house workers. The Labor Department didn’t lay out what this would cost tipped workers, perhaps because it didn’t want the public to know. An analysis by the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank, estimated that it could deprive employees of nearly six billion dollars in tips annually. (After a public outcry, Congress blocked the move.)

Trump recently claimed that the idea of eliminating taxes on tips was inspired by an exchange he’d had with a waitress he’d encountered at a dinner in Vegas. “She happened to be beautiful,” he told a group of blue-collar workers who were invited to the White House in June. “And she looked at me—she said, ‘Sir, there should be no tax on tips.’ ” This was “the coolest thing I’ve ever heard.” The idea was included in Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which he signed on July 4th; it was one of the few items in the package that some Democrats supported. Republicans released a video playing up the bill’s benefits for people like Peggy Weir, a waitress in Indiana who praises Trump for “fighting for the working men and women.” Many economists, however, consider the notion misguided. According to Yale’s Budget Lab, thirty-seven per cent of tipped workers don’t make enough money to pay any federal income taxes. Under the new law, casino dealers earning six-figure salaries with tips will receive large tax breaks, whereas busboys making poverty wages will get no benefit. And, though ending taxes on tips has a populist veneer, it won’t cost the owners of hotels and restaurants a penny. (This may be why Trump—himself a member of this class—embraced the idea.) The policy could even encourage employers to shift more kinds of work to tipped, subminimum-wage positions—thus reducing labor costs.

In February, Congressman Steven Horsford, a Democrat from Nevada, tried to rally support for an alternative measure called the Tipped Income Protection and Support Act, a bill that advocates a different approach. In addition to ending taxes on tips, it proposes to eliminate the subminimum wage that tipped workers are paid—a rate that, in sixteen states, is just $2.13 an hour before tips. Currently, the poverty rate among tipped workers is more than double the rate of other employees. Tipped workers are also more likely to rely on food stamps and other federal assistance.

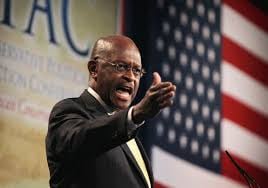

Raising the minimum wage is popular even in red states—in 2022, voters in Nebraska, which Trump won by more than twenty points, approved a ballot measure to increase it from nine dollars to fifteen dollars an hour in the course of four years. But raising the subminimum wage for tipped workers has proved far more challenging, owing, in no small part, to the power of the National Restaurant Association, an industry lobby that some labor advocates call “the other N.R.A.” The lobby, which has a partnership with the Arizona group and similar associations in all fifty states, emerged as a potent force in the nineteen-nineties, under the leadership of Herman Cain, previously the C.E.O. of Godfather’s Pizza. (In 2012, he unsuccessfully ran for President.) During Cain’s era, the N.R.A. helped to fight President Bill Clinton’s 1993 health-care-reform plan, which would have required restaurant owners to provide insurance to full-time employees. Later, when Clinton sought to raise the federal minimum wage from $4.25 to $5.15 an hour, the N.R.A. went along with the idea on the condition that the subminimum wage for tipped workers remain $2.13. This two-tiered wage system had existed since 1966, when an amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act permitted tipped workers to be paid a fixed portion of the standard minimum wage as long as gratuities covered the difference. For decades, the two rates rose in tandem. In 1996, they were decoupled, and the $2.13 federal subminimum wage has been locked in place ever since.

Robert Reich, Clinton’s first Labor Secretary, described this situation to me as “utterly outrageous.” He also called it a corporate giveaway that shifted the cost of paying restaurant workers from employers to customers and taxpayers: “American taxpayers are subsidizing the biggest restaurant chains in the country with food stamps and other benefits that go to their tipped workers, because these workers can’t afford to make it any other way.”

In 2021, an amendment to raise the federal minimum wage to fifteen dollars an hour and phase out the subminimum wage for tipped workers was attached to President Joe Biden’s pandemic-relief package. But the Senate parliamentarian removed the proposal from the bill, on procedural grounds. Bernie Sanders, then the Budget Committee chairman, forced a vote on the bill anyway, with the provision included. This decision sparked a furor among supposedly liberal lawmakers, according to Ari Rabin-Havt, Sanders’s legislative director at the time. “I got such an incoming of shit, like nothing else I’ve ever gotten, from Democratic legislative directors about how dare I force their bosses to take this terrible vote,” Rabin-Havt recalled. “I’m talking four-letter-word screaming—stuff I didn’t even get when we were doing something on Israel that people didn’t like.” The source of the rage wasn’t the raising of the federal minimum wage, a proposal that had broad support, but eliminating the subminimum wage for tipped workers and potentially incurring the wrath of the National Restaurant Association. In the end, seven Democrats and an Independent voted against the bill—among them Joe Manchin, of West Virginia, and Kyrsten Sinema, of Arizona—and the legislation was defeated, 58–42. A few weeks later, Manchin and Sinema spoke at the N.R.A.’s annual public-policy convention.

The outsized power of corporate lobbies is often attributed to their vast financial resources and to the absence of meaningful restrictions on campaign spending since the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision, in 2010. According to the nonprofit OpenSecrets, which tracks money in politics, the N.R.A., during the 2024 election cycle, disbursed nearly a million dollars to various pacs, party committees, and candidates, money that flowed to both Democrats and Republicans. But this isn’t the real source of the group’s power, Rabin-Havt said. “What makes them uniquely powerful is they have a grassroots network of members and supporters,” he said. “Everyone has restaurants in their districts. And all these elected officials are on the road a ton, so they’re in these restaurants, and they use them to host fund-raisers.” The N.R.A. knew, he said, that politicians were afraid of alienating these crucial constituents. “It’s very good at politics,” he conceded.

Few people have clashed more frequently with the National Restaurant Association than Saru Jayaraman, the founder of the U.C. Berkeley Food Labor Research Center and the president of an advocacy organization called One Fair Wage. As this name suggests, the group favors eliminating subminimum wages, a goal that it has tried to advance in numerous states, including Arizona, where it led the drive to place the One Fair Wage Act on the ballot last year. The proposal never made it to the referendum stage, because the Arizona Restaurant Association filed a lawsuit challenging the validity of signatures collected in support of the idea. The alternative pushed by the A.R.A. did appear on the ballot, after Republicans on the House Commerce Committee approved it, in a party-line vote.

It was a striking illustration of the restaurant lobby’s influence; nevertheless, Arizona voters ended up rejecting the industry-backed measure, by a three-to-one margin. Jayaraman sees this as a sign that, for all the N.R.A.’s resources and connections, resistance to its agenda is growing. She has been a leader in this area since 2002, when she co-founded an organization called the Restaurant Opportunities Center to help workers who had been employed at Windows on the World, a restaurant in the World Trade Center, after 9/11. The organization was soon flooded with appeals from servers at other restaurants who complained about more systemic problems—wage theft, sexual harassment, paltry pay. Jayaraman, who is Indian American, attributes the pervasiveness of some of these problems to gender and race. The idea of tips as a substitute for wages is “a direct legacy of slavery,” she said when we met at a Mexican restaurant in the East Village. After emancipation, the practice flourished at firms such as the Pullman Company, which hired formerly enslaved men as porters but declined to pay them a salary, causing them to rely on handouts from white customers. It’s no coincidence, Jayaraman said, that immigrants and Black people are overrepresented among the ranks of tipped workers today. So, too, are women, whose dependence on tips makes them vulnerable not only to harassment but also to discrimination. In a recent book, “One Fair Wage: Ending Subminimum Pay in America,” Jayaraman cites a study revealing that, in New York, Black women at dining establishments earn eight dollars an hour less than their white male peers, in part because customers tip them less.

The restaurant where we met is called La Palapa. Jayaraman said that she chose the place because it’s an establishment that pays employees a living wage, which, she argues, is not only fair but also good for business. (The restaurant’s owner, Barbara Sibley, agrees; she told me that eliminating subminimum wages had significantly reduced staff turnover.) During the pandemic, many workers at restaurants with less enlightened owners quit their jobs, Jayaraman noted, signalling their frustration with the low and erratic pay. Cities such as Chicago have since passed legislation to phase out the subminimum wage. “We are in a worker-power moment,” Jayaraman said. “Finally, we are winning.”

But, as she acknowledged, one of the N.R.A.’s most effective tactics has been persuading restaurant workers that “winning” entails defeating the agenda of organizations like hers. Last year, a canvasser named Mitchell Gaynor became aware of this strategy while campaigning for the passage of Ballot Question 5, a Massachusetts proposal to raise the base pay of tipped workers from $6.75 an hour to $15 an hour—the state minimum wage—by 2029. Gaynor, who grew up in a working-class household in the North Shore region of Massachusetts and has often worked in restaurants for meagre pay, figured that it would be easy to persuade his peers to back the proposal. Instead, he “lost friends over this,” he said, as many servers became convinced that approving Question 5 would force restaurants to raise prices so high that customers would either stop tipping or stop eating out. This was a message crafted by the Massachusetts Restaurant Association—which, like all the state groups, has a written agreement with the N.R.A. that reflects a shared mission. The notion was often relayed to tipped workers directly by their bosses. One waitress told me that the owner of her restaurant pulled servers aside before a shift and urged them to “get the word out to vote no on Question 5,” so that their tips wouldn’t be taken away. In some restaurants and bars, signs saying “Vote No on 5” were hung in prominent places, to insure that customers got the message, too. Another waiter sent me photographs of the checks that he and his co-workers were handing out to diners. “Your Crew Votes ‘NO’ on Question 5,” they stated at the top. (The waiter voted yes, a fact that he hid from his boss.)

The N.R.A.’s Massachusetts campaign was a huge success. In a liberal state where Elizabeth Warren, one of the Senate’s fiercest champions of labor, cruised to reëlection, nearly two-thirds of voters rejected Question 5. “We got our asses kicked,” Gaynor said.

I recently visited the N.R.A.’s headquarters, in Washington, D.C. Sean Kennedy, the executive vice-president of public affairs, told me that it’s entirely reasonable for bartenders and waitresses to fear that eliminating the “tip credit”—the difference between the minimum wage and their base pay—will be detrimental to their interests. Kennedy has a polished manner and a fluency with social policy that was honed on Capitol Hill. He was an aide to the former Democratic Missouri congressman Dick Gephardt and a special assistant for legislative affairs to President Barack Obama before becoming a corporate lobbyist. Kennedy told me that, if labor costs suddenly tripled, restaurants would need to either raise prices (which could lead customers to tip less) or hire fewer people. Both scenarios would harm the servers whom the policy was designed to help. Question 5 in Massachusetts and similar measures elsewhere have not failed because of the restaurant lobby, he insisted, but because owners and employees “recognized what was at stake and engaged their local policymakers to say, ‘This is a bad idea.’ ”

Kennedy continued, “Every business economist has said that, if you raise the minimum wage, there’s going to be a reduction in jobs that’s going to be particularly intense in labor-intensive industries.” For much of the twentieth century, this was indeed the prevailing view among economists. But in 1994 the American Economic Review published an article that challenged this belief. Its authors—David Card, who would go on to win a Nobel Prize for his research on labor markets, and Alan Krueger, then a professor at Princeton—tracked the employment levels at fast-food restaurants in New Jersey before and after the state raised its minimum wage, then compared these data with the situation in neighboring Pennsylvania, where the minimum wage hadn’t changed. They found “no indication that the rise in the minimum wage reduced employment.” In 2010, a team of economists examined three hundred and sixteen pairs of counties on the opposite side of state borders where, during a period of sixteen and a half years, the minimum wage rose on one side but not on the other. They, too, found no adverse employment effects.

Michael Reich, a labor economist at U.C. Berkeley who co-authored the 2010 study, told me that most economists today no longer believe that raising the minimum wage will substantially reduce employment among low-wage workers. Doing so will cause restaurant prices to rise, he acknowledged, but the change will be far smaller than many people assume, in part because raising the minimum wage often lowers the cost of recruiting and retaining workers. In a recent policy brief, Reich examined the effects of California’s adoption, in 2024, of a twenty-dollar minimum wage for fast-food workers, a policy that the N.R.A. strenuously opposed. He found that the measure has led to price increases of less than two per cent—roughly six cents on a four-dollar hamburger. In February, Reich’s analysis was cited, misleadingly, by the Employment Policies Institute, which opposes raising the minimum wage. A blog published by the group quoted a sentence in which Reich made note of “a very small negative employment effect” from California’s wage increase. It didn’t quote the next line of the study, which explained that, when a statistical method controlling for trends in related industries and other variables was used, there was no decline in employment. The Employment Policies Institute has received funding from the N.R.A. and was founded by Richard Berman, a retired lobbyist and public-relations executive who specialized in creating nonprofit organizations that served as fronts for corporate clients, including the tobacco, alcohol, and restaurant industries.

Michael Reich’s research focusses on the fast-food industry, not on independent, full-service restaurants. Such businesses would be more endangered if the tip credit were eliminated, Kennedy told me. But the claim that they would go bankrupt if they had to pay waitstaff and bartenders the full minimum wage is belied by the fact that seven states, including Alaska, Minnesota, and California, already require restaurants to do this. Sylvia Allegretto, a labor economist who studies the minimum wage, noted that people still eat out (and tip) in those states: “I’m here in Oakland, where the restaurant industry is booming and everyone tips.”

In 2023, Allegretto published a study that compared “high-road” states that have no tip credit and “low-road” states, where restaurant workers get $2.13 in base salary. In the high-road states, the poverty rate of waitstaff and bartenders was significantly lower. And restaurant jobs had not grown scarce. In fact, between 2012 and 2019, the number of businesses and the rate of employment growth in full-service restaurants were higher in these states.

The N.R.A. claims that there’s no need for restaurants to pay tipped workers the full minimum wage, because servers already do so well. “You can bring home a really impressive paycheck,” Kennedy told me. Before we met, the organization had sent me some industry data, including this statistic: “The median hourly income of a tipped server is $27/hour, with the top earners making over $41/hour and the low end making $19/hour.” It came from a survey of more than two thousand full-service restaurants that the N.R.A. itself conducted. No economist would regard a lobbying group as a reliable source for such information. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median hourly pay of waiters and waitresses (including tips) was $15.36 in 2023. A quarter of full-time servers earn less than twenty-four thousand dollars a year. Although waiters in fine-dining establishments can make several times this amount, there are far more low earners who work at places such as ihop and Cracker Barrel. Restaurant servers are also much less likely to receive health insurance, paid sick leave, and other benefits than other private-sector employees.

Allegretto acknowledged that small, family-owned restaurants could “struggle disproportionately” if the tip credit were eliminated, and that these institutions helped give many communities their charm. “We definitely don’t want to lose the restaurants that make your neighborhood so wonderful to live in,” she said. But there are ways to help such businesses—lowering their tax burden during a transition period, for example. Countries that have never expected servers to rely on tips, including Italy and France, are full of family-owned restaurants. “Why are we the only country in the world doing this?” Allegretto asked. “The model we have is very unfair, and it’s not necessary.”

One afternoon, I met a bartender named Max Hawla, who lives in Washington, D.C., where the debate about tipped workers has been particularly heated in recent years. Hawla is in his early thirties, with a laid-back manner and a boyish face framed by a mop of reddish-blond hair. In 2018, he was working at a bar in Dupont Circle when he heard about Initiative 77, a ballot measure backed by Restaurant Opportunities Centers United, which proposed to raise wages for D.C. servers from less than four dollars an hour to the standard minimum wage by 2026. After his manager told him that the measure would “mess up our wages,” Hawla became opposed to the idea, to the point of changing his profile picture on Facebook to an Initiative 77 sign with a slash through it.

Despite stiff opposition from the N.R.A. and the Restaurant Association Metropolitan Washington, voters approved Initiative 77, by a nearly twelve-point margin. Later that year, under pressure from the restaurant lobby, the D.C. Council overturned it. When Hawla heard this, he was relieved. Sometime later, he visited a friend in Seattle. One night, they went to a speakeasy and chatted with the bartender. Hawla thought that he had a “very bro-ish, bodybuilder vibe,” and was the kind of guy who probably made a nice living just on tips. Hawla decided to ask him what he thought of the tip credit.

“What’s a tip credit?” the man said. There wasn’t one in Washington State or in Montana, where he’d grown up.

“You know—because you get tips, your employer can pay you a lower wage,” Hawla explained.

“Well, that sounds stupid,” the bartender said, noting that he made fifteen dollars an hour, and still got good tips on top.

In 2022, a proposal to phase out the tip credit in D.C. was again placed on the ballot. This time, Hawla voted for the measure, having come to believe that he’d been fed “a lot of misinformation” that was designed to get tipped workers to fight against their own interests. The proposal, Initiative 82, passed by nearly fifty points, seemingly settling the matter. But this past January a friend alerted Hawla that the D.C. Council was hosting a public hearing on the issue. The friend, a fellow-bartender named Rachelle Yeung, had been working a shift at a brewery when a canvasser dropped off a flyer encouraging servers to attend the hearing and testify about the “negative impact” Initiative 82 was having. “Have you or your co-workers lost hours?” the flyer asked. “Lost jobs?”

Workers who’d experienced these problems were instructed to contact a server named Joshua Chaisson, whose e-mail address was printed at the bottom of the flyer. Chaisson had personally handed a flyer to Yeung. A week later, Chaisson, who goes by @MrTipCredit on X, appeared at the hearing in a black sweatshirt emblazoned with the logo “save the tip credit rwa”—the initials of a group called the Restaurant Workers of America. This organization, which Chaisson co-founded, first attracted media attention in 2018, after its members began speaking out against campaigns to eliminate the subminimum wage. Some media outlets credulously depicted it as a grassroots network of servers who opposed an imprudent policy shift. “We keep screaming from the rooftops, ‘Please don’t help!’ ” one member told BuzzFeed News. The tone of reporting on the group changed after the Columbia Journalism Review published an article revealing that most of its members were restaurant owners, each of whom paid between a hundred dollars and five hundred dollars to join. BuzzFeed News later reported that the Restaurant Workers of America’s most prominent spokesperson, Chaisson, had strategized with the P.R. firm founded by Richard Berman, the man who created fronts for lobbying groups.

Sean Kennedy, of the N.R.A., told me that his group has no financial ties to the Restaurant Workers of America, though he acknowledged that the organizations have had “intel-sharing conversations.” In recent years, Chaisson appears to be keeping a lower profile—he didn’t respond to a request for an interview—but he’s continued to push for maintaining the tip-credit system. His crusade against Initiative 82 might seem strange, given that he waits tables in Portland, Maine, more than five hundred miles from the nation’s capital. Nevertheless, at the hearing, he blasted the measure for creating a “dumpster fire” in D.C., saying that restaurants were closing at a record pace and servers were losing hours and jobs. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics paint a less dire picture. Since Initiative 82 was adopted, employment at full-service restaurants in D.C. has hovered at about thirty thousand jobs. Nonetheless, in June the D.C. Council overrode voters for a second time. It paused the minimum wage for tipped workers, which was scheduled to go up to twelve dollars an hour in July, at its current level—ten dollars an hour. The city’s minimum wage is $17.95.

Nina Mast, an analyst at the Economic Policy Institute, has studied the methods of the restaurant-industry lobby closely. She’s an expert on child labor, which has grown increasingly pervasive in recent years, as states have loosened restrictions on the number of hours that teens can legally work on school nights, and permitted their involvement in alcohol service and hazardous jobs such as roofing. In Iowa, Florida, and several other states, the restaurant lobby has pushed for these policies, she told me, in part to address what the lobby claims were labor shortages caused by the pandemic. Recently, Kennedy was quoted in a press release introducing a federal bill that would let teens work longer and later. N.R.A. associations and their members have portrayed the changes as harmless, family-friendly reforms. “What they do is recruit mostly white teens who work at a family-owned small business to testify that working a few extra hours a week will benefit them,” Mast said. “Of course, this is strategic. They don’t want lawmakers to hear from teens who are getting injured working in slaughterhouses owned by multinational corporations or who can’t stay awake in school, because they’re being scheduled to work late on school nights. But these are the young people who will be harmed.” The N.R.A.’s agenda went far beyond defeating efforts to eliminate the subminimum wage, she added: “The N.R.A. and its state affiliates are heavily invested in lobbying for anti-worker policies across the board, in areas from paid sick leave to overtime pay.”

Jessie Danielson, a member of the Colorado State Senate whom I met in May, has seen this more sinister face of the restaurant lobby. Danielson is a progressive Democrat and an outspoken champion of workers’ rights. One bill she recently co-sponsored would require the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment to publish on its website the names of employers who engaged in wage theft—a widespread problem in the restaurant industry—and report these violations to licensing and permitting bodies. Last year, a study published by the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations estimated that, in the Denver-Aurora metropolitan area, forty-five thousand workers a year were paid below the minimum wage, costing them, collectively, at least a hundred and thirty-six million dollars in earnings. Among the occupations subject to the highest violation rates were servers, hosts, and chefs. Few people would defend employers who steal money from their workers, but the Colorado Restaurant Association opposed the wage-theft bill. Danielson also sponsored a bill called the Worker Protection Act, which sought to eliminate an onerous requirement for workers seeking to form a union: that they hold a second election, and win seventy-five per cent of the vote, a burden unique to Colorado. The Colorado Restaurant Association opposed this measure, too. “Does this lobby oppose anything that gives workers rights?” she said. “In my experience, yes.”

The Colorado restaurant lobby did support one piece of labor legislation this year—a bill, H.B. 1208, that proposed lowering the base pay of tipped workers in cities that have raised their minimum wages above the statewide level. One such city is Denver, where the measure would have cut the minimum wage for tipped workers from $15.79 to $11.79. The bill’s supporters claimed that this was necessary because labor costs were decimating Denver’s restaurant industry. They cited the fact that since 2022 the number of licensed establishments in the city had fallen by twenty-two per cent. This figure, which appeared in the Denver Post and was circulated widely, came from the Department of Excise and Licenses. But, as Denver Labor, a division of the city’s auditor’s office, pointed out, that department didn’t give licenses only to restaurants; it issued them to all food and retail establishments, a category that had recently been redefined, with many food trucks and concession stands removed from the department’s database. As the department itself made clear, this meant that the statistic was an unreliable barometer of the restaurant industry’s health.

After meeting Danielson, I visited the offices of the Colorado Restaurant Association to speak with Sonia Riggs, its president and C.E.O. Riggs maintained that labor costs were devastating Denver’s restaurant scene. “I talk to restaurateurs every day who are crying or are looking for an exit strategy,” she said. “When you hear those stories over and over, it literally breaks your heart.” Riggs went on to frame H.B. 1208 as a matter of fairness, not only for struggling owners but also for back-of-house workers who didn’t get tips. “Why are the lowest-paid people in the company the least important and the ones that nobody wants to help?” she asked. Servers in Denver, she said, earned an average of thirty-nine to forty-two dollars an hour—far more than chefs and dishwashers.

This was another statistic touted by H.B. 1208 supporters. It came from a survey of a hundred and thirty restaurants which was conducted by a possibly biased source: the Colorado Restaurant Association. If true, it would mean that the typical server in Denver makes more than seventy thousand dollars annually. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, however, the average salary of bartenders and servers in Denver is less than forty thousand dollars; economists say that this isn’t enough for a single person to cover living expenses in the city, much less to support a family. “These are economically vulnerable people,” Matthew Fritz-Mauer, the executive director of Denver Labor, told me.

His view was echoed by Joseph Mitchell, a waiter at the Alamo Drafthouse, in Littleton. He told me that last year he made forty thousand dollars working full time. He lives paycheck to paycheck, he said, without health care, and couldn’t imagine getting by if his hourly salary was cut by four dollars.

I met Mitchell at the Weathervane Café, a restaurant in Denver whose owner, Lindsay Dalton, has vocally opposed H.B. 1208. Dalton admitted that, in many restaurants, there were tensions between front-of-house and back-of-house employees. This was why she and her husband, who co-owned the café, pooled all tips and divided them evenly among the staff. Nothing prevented restaurants in Denver that cared about fairness from doing the same, she noted. The most surprising thing about H.B. 1208, she said, wasn’t that the restaurant lobby had pushed for it but that its sponsors were all Democrats. Judy Amabile, a state senator from Boulder, was one of them. Amabile, a co-founder of a sports-water-bottle company, told me that she supported the bill because she believed that restaurants in places such as Boulder were hurting, and that flexibility on the tip credit was needed to avoid damaging “one of the big economic drivers of our community.” A spokesperson for EatDenver, a coalition of more than four hundred and fifty independent restaurateurs, told me that the rising cost of labor was their biggest concern. But the damage didn’t seem to be as grave as the restaurant lobby claimed. In 2023, a study by the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment found that, in the two years after Denver raised its minimum wage above the state level, business boomed. Per-capita sales-tax revenues at bars and restaurants in the city increased by eighty-five per cent—double the rate of the rest of Colorado.

Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez, a member of the Denver City Council, appreciated the challenges that restaurant owners faced. Her parents started a restaurant some years ago, and they had to close it after having problems with the landlord. But she didn’t believe that cutting workers’ wages was the only solution. “Can we look at the inflation of food costs—or the cost of rent?” she asked. Gonzales-Gutierrez was one of thirty-seven legislators who signed a letter opposing H.B. 1208, maintaining that it undermined the authority of local governments to set the minimum wage. On this occasion, as in the past, she said, the Colorado Restaurant Association presented itself as the champion of mom-and-pop restaurants while advancing an agenda that she felt primarily benefitted large chains. In 2023, when she was a state representative, the N.R.A. lobbied against a fair-workweek law that would have required employers to give workers advance notice about their schedules. The law, which she co-sponsored, would have applied only to businesses with more than two hundred and fifty employees. The restaurant industry brought out more than eighty people to speak against it at a hearing, including the Latino owner of a small Mexican restaurant. “It wouldn’t even apply to them, but they testified,” she said.

Kjersten Forseth, the legislative consultant for the Colorado A.F.L.-C.I.O., told me that she’d struggled to contain her fury as she watched the leaders of Colorado—a blue state where Democrats control all branches of government—advance a bill to cut the wages of servers, especially after an election in which many working-class voters left the Democratic Party because they felt that it didn’t care about them.

A coalition of progressive groups, including Towards Justice and Coloradans for the Common Good, mounted strong resistance to H.B. 1208, and the bill’s sponsors were forced to amend it, stripping out the mandatory wage cuts and settling for giving municipalities more flexibility to alter the tip credit in the future. Colorado’s legislature also approved the Worker Protection Act, removing the burden on employees to hold a second election before forming a union. But Governor Jared Polis, a tech entrepreneur, promised to veto the bill. Before he did so, reports surfaced that Polis had floated to labor advocates the possibility of not vetoing it if other items returned to the negotiating table—including the original version of H.B. 1208.

Dennis Dougherty, the executive director of the Colorado A.F.L.-C.I.O., told me that the Colorado Restaurant Association was in on these negotiations, and that Polis appeared to expect the A.F.L.-C.I.O. to make a deal that sold out tipped workers to advance its agenda of facilitating unionization. But it refused to do so. Dougherty doesn’t regret the decision, even though Polis did veto the unionization bill. “They thought we were going to roll these workers,” he said. “We didn’t.” ♦ (Eyal Press, The New Yorker).

Restaurants themselves, with few exceptions, are not strong, profitable businesses. Their margins are slim.

The Second “NRA” doesn’t try to help the whole industry. It is an organization, based on a false assumption that the owners and workers in restaurants are natural enemies.

Many restaurants are on the verge of failing - a terrible situation for the owners, but even if a restaurant is surviving, the situation for its workers may be dire.

The NRA does not work on the assumption that it should better the circumstances of everyone in a high risk industry. Instead, it drives an unnecessary wedge between underpaid workers and at risk restaurant owners.

Remember Herman Cain, a former President and CEO of the National Restaurant Association (NRA), who ran for the presidency in 2012. He served as head of the NRA from about 1996 to 1999, and then launched his 2012 Republican presidential campaign in May of that year. He was a member of the Tea Party.

Cain’s 9‑9‑9 Tax Reform Plan was based on a flat tax, which prominent economists like Paul Krugman made clear would shift more of tax responsibilities from the rich to the poor.

Maybe a good motto for us all is be wary of whatever Trump and the GOP favor. Drill down.

We need to reject the idea of “sides” between owners and workers.

We need real think tanks, not partisan ideologues, to provide answers on how to strengthen at risk industries, like restaurants.