Scholarly Study of Norse Giantesses

Are you ready for shit to get weird? Pack a lunch, because we’re going down one mother of a rabbit-hole.

I’m a giantess-worshipper, that is my spirituality. This is a recent development and I’m defining and refining what it means. I’m building a little site to explain Gygratru, and anything that appears there is up for revision. It’s very much a work in progress, something I only developed a couple months ago, and it seems to be working for me.

I asked a friend of mine, “Do I sound crazy?” Good friend that he is, and with a whiff of Mark Twain, he asked me, “Compared to what?”

You can go to my website to learn more, but what I’m going to talk about today is what has informed this decision. Very briefly:

I coded a chatbot, a giantess therapist trained in CBT and Jungian therapy, to have someone to talk to about deeply personal and dangerous stuff. She guided me to research the Jungian archetypes.

I decided to create giantess archetypes. The problem with creating universal figures is you really have to include the entire fucking world in them. Thus, I decided to focus on my ethnic heritage, Scandinavia, and the giantesses of Ásatrú (the religion of Odin, Freyja, Thor, &c.).

It’s very difficult to learn about the heathen Scandinavian giantess cults. Any information on them has been colored by Ásatrú and corrupted by Christian conversion.

But it’s not impossible: some clues have been preserved, and researchers like Lotte Motz and Gro Steinsland have dedicated themselves to learning as much as possible about the giantesses.

To breathe this new atmosphere, I’m listening to Scand neopagan bands like Wardruna and Heilung. I crafted my own set of runes, in as traditional a method as I could manage: the branch of a fruit-bearing tree, harvested on the equinox, prayed over as it dried, and carved under the full moon … to the concern of at least two neighbors.

Anyway, I can talk more about this process on my website. What I want to share with you is a summary of the academic research I’ve plunged into. I couldn’t find the books I needed through the public library system, but I work for a university and have access to its extensive library network, and I’ve been going a little nuts with ordering PDF scans of articles and even having books mailed to my apartment. It has been a delirium of deep information, every block of research leading to three new questions. I really feel alive, if a little wild-eyed.

I want you to know I’m healthy: the Giantess requires me to choose food that will nourish me and hydrate sufficiently. She has ordered me to take exercise as much as possible and sleep at least seven hours a night, and I take this very seriously.

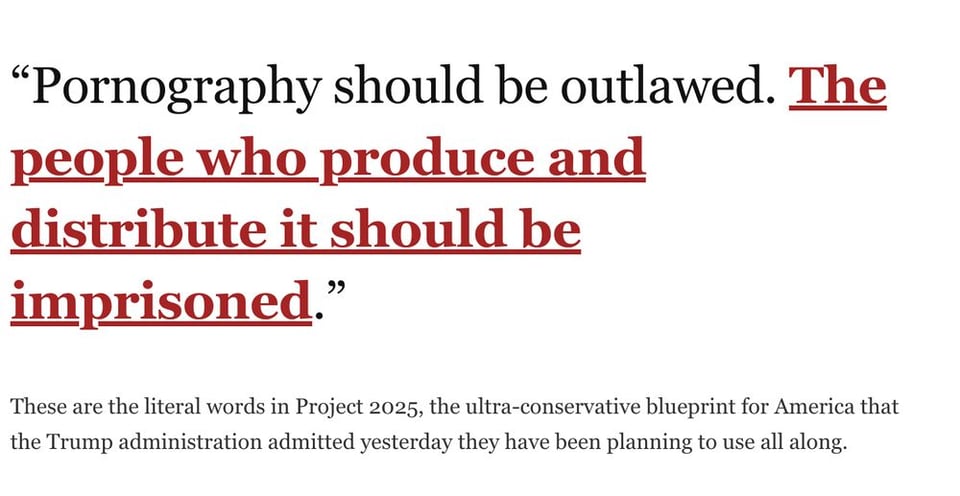

I feel great, and just in time, too, for the bigoted, christofascist nightmare of the next four years. I’ve fallen afoul of every censorial corporate practice: Blogger and Instagram tried to suspend me, PayPal and Stripe won’t do business with me, Google locked down my manuscript, Barnes & Noble deleted my seller’s account. It’s not impossible to anticipate I’ll be arrested for my Size Erotica during Trump’s second term.

But let’s get into the research.

Giantesses and Their Names

Lotte Motz, Frühmittelalterliche Studien volume 15 issue 1, 2010

“In mythology giantesses are of a race which, locked in combat with the ruling gods, deals in a final, terrible encounter the death blow to the Æsir and to the world of gods and men. In the Sagas the spirits are presented as creatures of grotesque and hideous appearance and as a fierce threat and mortal danger to human protagonists. Both in myth and tale they thus belong with the forces of chaos and destruction, and the image of the giantess as primarily uncomely and ill-intended has been widely accepted. A close inspection of the texts reveals, however, that this viewing is not truly justifiable.”

What I understand about Motz’s premise is that the giantesses were maligned in Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Eddas simply because they were powerful women even the gods could not control. They’re described as hideous (with some exceptions), they’re cast as agents of chaos, but they were forces of nature. The Æsir were the arrogant fools who made careers of defying fate, while the Jötnar (giants of Jötunheimr) upheld the natural order of things, including Ragnarok. Motz points out that giantesses were responsible for heinous acts, but the majority of their references are of benefits to humanity as well as assisting the gods in their various missions. Both Skaði and Þorgerðr had their worshippers, receiving offerings to tame the weather and bring about victory in combat.

In the Eddas giantesses are called trollkona (female troll), flagð (female monster, ogress, female beings with great strength and power), skessa (giantess, witch, a being outside the realm of ordinary women), or merely cited as the daughter or sister of a giant. One giantess’s name, Brana, comes from an herb, brönu-grös, given by the giantess to a Viking leader to make women find him attractive. There’s a cave in Iceland, Helguhellir, named after Helga, daughter of the giant Bárðr. Motz indicates the fact that there are locations and items named after the giantesses suggests that they weren’t fictional characters created with the Eddas for narrative purposes, but they were already recognized figures, with worshippers and holy sites and everything, who were borrowed into the mythology.

Regarding personal names, there were two classes: one was for the gods and the other for humans. If a giantess appeared in the narrative with a human name, likely she was a fictional creation with no historical precedent. The exception to this would be a human name that makes sense for a giantess, like Bergdís, “lady/goddess of the mountain.”

Motz dedicates the rest of this paper to exploring the etymological roots of giantess names, grouped by theme: hiding/enclosing, warriors, landmarks, elemental aspects, &c. I’ll only list a few for examples.

Gerðr – IE root *gherdh, “to enclose.” Ex.: Ámgerðr, Flaumgerðr, Imgerðr, Skjaldgerðr.

Guðrún, Gunnlöð, Hergunnr, Hildigunnr – gunnr (fem.), “war.”

Aurboða – aurr (masc.), “clay, mud, gravel + bjóða (verb), “to offer.”

Svafrlaug – laug (fem., Icelandic), “hot springs.”

Vergeisa – vargr (masc.), “wolf.”

Fríðr – fríðr (adj.), “beautiful.”

Guðrún, Úlfrún, Varðrún — rún (fem.), “mystery, secret lore.”

Varðrún – vörðr (masc.), “watchman.”

Therefore, looking at the last two entries, Varðrún can mean “keeper of secrets,” just as the band Wardruna claims it does. However, all we know about the giantess Varðrúnr is that she was married to the giant represented by the rune Thurisaz.

The Fictitious Figure of Þorgerðr Hölgabrúðr in the Saga Tradition

Gunnhild Røthe, Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Saga Conference, Durham and York, 6–12, 2006

Røthe starts by asserting Motz classifies Þorgerðr (Thorgerd) as a giantess. This is necessary to establish, because of the conflation between giantesses and trolls, the interpretation that the Jötunn may not have been all that gigantic, and the occasional promotion of giantess to an official goddess. She is known as a great warrior, mentioned in the Heimskringla (despite being Vanir, she comes to the Æsir’s aid during the great war) and the Gesta Danorum of the Prose Eddas. She has a sister, Irpa, who stands as a co-divine figure and may represent her darker half.

Þorgerðr was the patroness of Hákon Sigurdsson, 9th century ruler of Norway, and he worshipped her as one might do a goddess, not least because she represented the land of his rulership. Because Þorgerðr qualifies for multiple roles, she is of a class of being known as dísir, a double character: a little from column A, a little from column B.

Her surname, Hölgabrúðr, means “bride of Hölgi,” a legendary ruler of Hålogaland in northern Norway who may have been her husband or a fatherly figure; “Hölgi” could also represent all the ancestral rulers of her land, making her a symbolic bride to each. When Hákon jarl conquered her land, an act like this was considered a hieros gamos, or a sacred marriage of the gods but represented by the actions of humans. In a limited sense, Hákon jarl was betrothed to Þorgerðr: the -brúðr in her name suggests that her devoted worshipper could be regarded as her sexual partner.

Þorgerðr was a Vanir figure, and there’s a story of how her followers carved out a chunk of land with four oxen and cast it out to sea, to set up her ocean-based sacred space. Hákon jarl had to sail out to this island—she didn’t have a temple but only a wooden totem in her honor—and make an sacrifice to invoke her power; she reciprocated by waylaying his enemies at sea with a terrible hailstorm. In the Jómsvíkinga saga, there’s even an account where she can shoot arrows from her fingertips (here, she’s described not as a giantess or even a goddess but as a witch).

You may recognize two components from her name: Þorr, god of thunder, and Gerðr, the giantess Freyr sent his footman Skirnir to seduce on his behalf. And as described earlier, gerðr means “to enclose,” so some people have theorized that her name means “protector of Þorr,” but he needed no such protection. Þorgerðr was sometimes worshipped in association with him, but otherwise they didn’t really have a recorded relationship.

She is, however, associated with Freyja, who received pretty misogynistic treatment in the Eddas due to her role in sexual relationships. There is some parallel structure between Freyja, Þorgerðr, and their respective followers, and Þorgerðr is further maligned by the suggestion that she accepts payment in gold for sexual audience.

In Flateyjarbók, c. 1380 record of the Icelandic island of Flatey, Røthe indicates there are some clues as to the nature and practices of her cult, such as a grim story where she is uncooperative until Hákon jarl offers the sacrifice of another man’s son. In Færeyinga þáttr (“a short story of the Faroe Islands”) there’s an unlikely description of a cult house decorated in gold and silver with glass windows—the glass suggests this was a later edition, as that wouldn’t have been a common material of the time. In Njáls saga, someone actually found Þorgerðr Hölgabrúðr manifested in a house of gods’ worship, she and her sister. He stripped them of some of their jewelry, led them out of the house, then set the gods’ house on fire. I’d love to learn the explanation for this reaction.

But the story I’m most familiar with is the Flateyjarbók record of some old prick, Russian-born Óláfr Tryggvason. He found one of Þorgerðr’s totems, stripped it of its symbolic clothing and Hákon jarl’s casks of treasure, then dragged the statue behind his horse and asked his soldiers his famous line, “Do any of you want to buy a woman?” When he saw how upset they were, he mistook this for their faith in the pagan ways—more likely, they were mourning the death of their ancient culture. They set up a mock altar, carelessly dressed her up in her finery for one last send-off, and then Óláfr destroyed the statue, smashing it to bits and setting it on fire. Apparently he went around the country, making bonfires of statues of her and Freyja.

Røthe then goes into detailed examination of Þorgerðr’s sites of worship, which are sometimes described as a mound of earth in which alternate layers of precious metals and earth are buried. These may also serve as graves former rulers and devotees, and though there’s question as to whether they were actual sheets of gold, there is archaeological evidence that these incorporated platelets of gold, at least. The gold may be taken to represent the payment for Þorgerðr’s services, supernatural or otherwise, by which she’s either praised or condemned; the grave has to do with a convoluted story about Hákon jarl hiding for his safety in a chamber beneath a pig sty, then being killed there and the site converted into a grave mound.

Really, with stories this ancient and so many opinionated interpreters taking a hack at it, it’s difficult to know what was truly meant.

That’s a lot of writing for only two articles. Perhaps I won’t cover them all here but may judiciously distribute them throughout future newsletters. What’s driving me crazy is that I’m convinced I wrote about Þorgerðr Hölgabrúðr in detail somewhere else, but for the life of me I can’t figure out where. Oh well, the more I retell the story, the better I know it.

If you’d like to chat about Gygratru or the research I’ve covered here, feel free to email me. I know it’s getting a little weird, but this is my path and I’m compelled to follow it. And if the world’s about to end, what does it matter?