ARTchivist's Notebook: On Abstraction

Abstraction is at the heart of communication. Perhaps it can be a refuge from the onslaught of the "real."

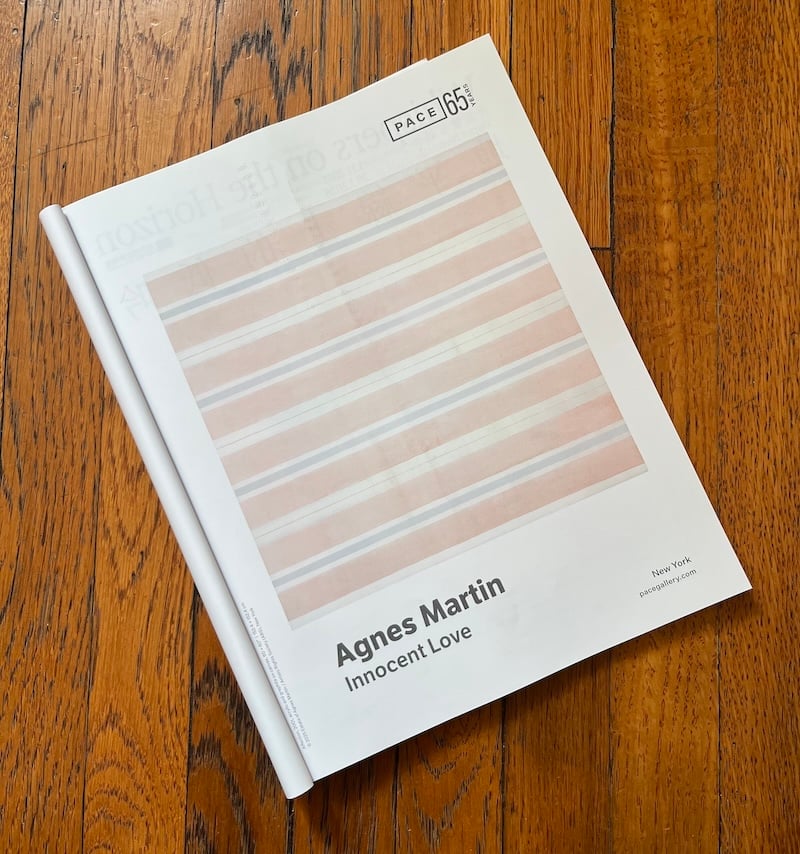

I opened up the latest issue of Art Review the other day to an ad for an Agnes Martin exhibition and was surprised to experience a surge of tender feeling. The image was a painting — horizontal stripes in pale pink, white, and light blue — not uncommon for Martin (did she ever do anything uncharacteristic?), but not one I’d seen before. In fact, I haven’t been in front of a Martin for years; I generally like her work, but don’t go out of my way to see it. Why was I so moved? And is my emotional life impoverished or enriched because a reproduction of an abstract painting can elicit such feeling? The simple explanation is that I know who Martin is and have had similar experiences in front of her work. The image was just a reminder, and yet I was surprised by the immediacy of my response.

It made me think about what abstraction can convey, and whether it does this only for those who are “initiated” into its particular language and culture. I suspect not, because children respond to abstraction. In 2015, my then ten-year-old child confidently declared a retrospective of Noah Purifoy’s work at LACMA — much of which is abstract — “the best art show ever” despite never having learned anything about abstract art.

The earliest art, like cave paintings, is abstract. It was a way of making sense and communicating what was important to humans about the world around us. Japanese art critic and philosopher Yanagi Sōetsu located this intersection of human and nature in patterns — abstract designs derived from perceptions of the natural world.

Anyone can visually apprehend bamboo grass, but the way it is viewed depends on the person. Not everyone perceives the beauty of bamboo in the same way… Bamboo becomes beautiful only when it is seen as beautiful. A bamboo pattern is an arrangement made by the human mind. All patterns are the product of human perspective. A pattern is not a realistic depiction of nature but a new creation.*

Abstraction is what happens when human and nature meet; it is the result of experiencing something that moves us. In this sense, all communication — writing, speaking, metadata ;) — is abstract pattern, so why wouldn’t another human’s arrangement of stripes evoke a feeling?

This might seem like an obvious point, but I think it’s important to remember as we see our cultural landscape continue to shift towards lies and deep fakes that feel increasingly “real.” Abstraction starts to look like a refuge.

Opportunities & Resources

Please consider signing this statement, co-authored with input from arts and cultural professionals from seventeen different cultural institutions, under coordination of the National Coalition Against Censorship and the Vera List Center for Art and Politics. It affirms, as cultural workers, “our democratic responsibility to act as guardians of artistic freedom and independent thought,” independence in programming and in mission, and solidarity with other institutions who are facing political pressure.

IndigenizeSNAC Call for Focus Group Participants

IndigenizeSNAC is testing SNAC as a potential tool for finding and accessing distributed Native and Indigenous archival records. They are looking for community members who have gone to archives or have done archival research (but do not have a professional archival role or training) to engage in two compensated focus group discussions between now and late-January.

The Sustainable Heritage Network has been promoting their wealth of resources on preservation topics, geared specifically for Indigenous communities, but containing lots of great knowledge and advice for everyone. They have all manner of free, online resources related to the care and conservation of images and photographs, artifacts and 3D objects, and cultural protocols and rights management.

*Yanagi Sōetsu, “What is a Pattern?” (1932) in The Beauty of Everyday Things, Yanagi Sōetsu. Michael Brase, trans. Penguin Books, 2017.